Hans-Sachs-Haus, 1924-1927. Architect: Alfred Fischer. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Hans-Sachs-Haus, 1924-1927. Architect: Alfred Fischer. Postcard.

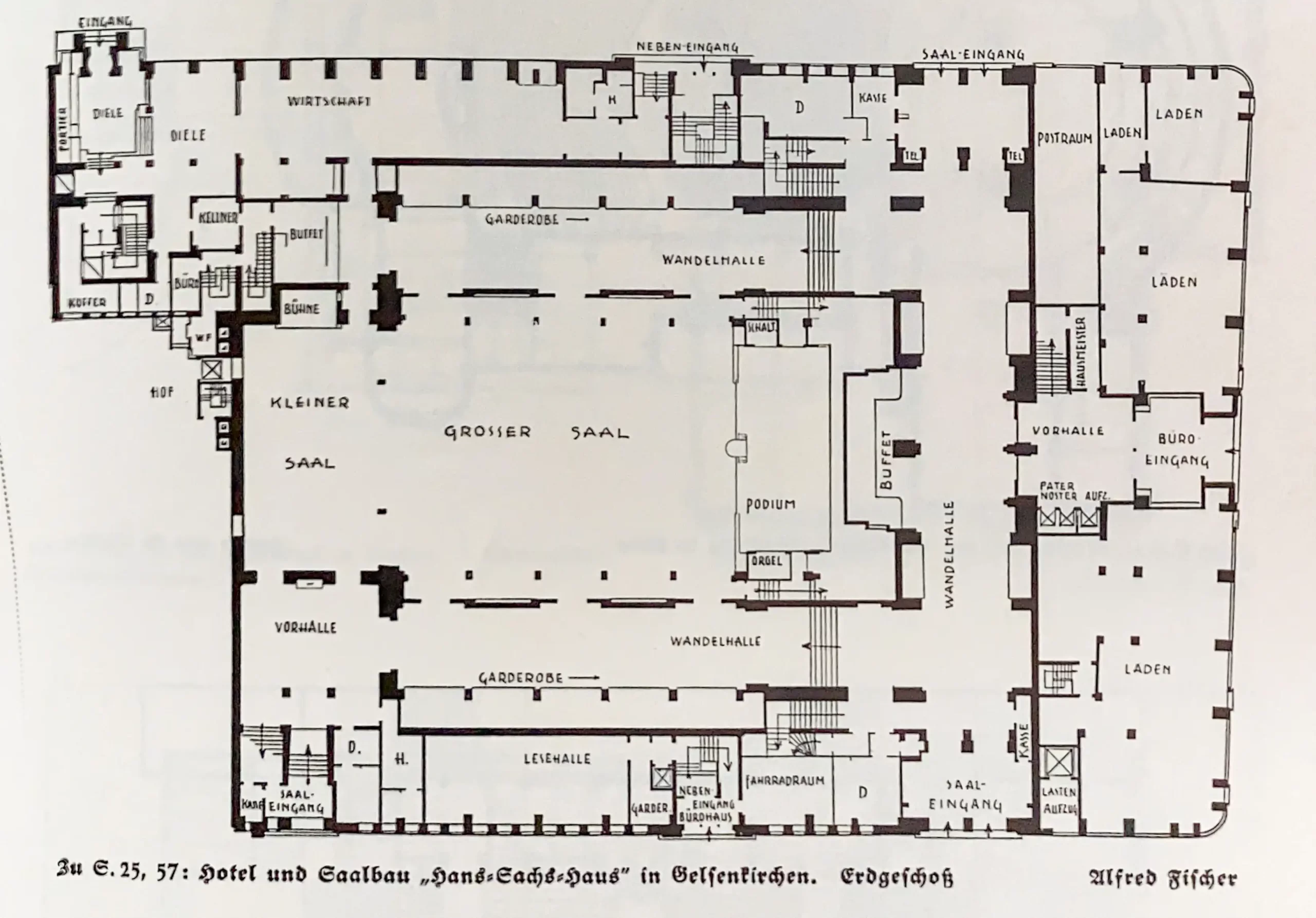

Hans-Sachs-Haus, 1924-1927. Architect: Alfred Fischer. Floor plan.

1924 – 1927

Architect: Alfred Fischer

Ebertstraße 11, Gelsenkirchen, Germany

The Hans-Sachs-Haus was built between 1924 and 1927 according to plans by Alfred Fischer as a municipal administration and office building with a hotel and concert hall.

The technical execution and the local construction management were carried out by the building department of the city of Gelsenkirchen with the city planner Max Arendt and the master builder Boeke.

Stylistically, the Hans Sachs House can be seen as a link between Expressionism and New Objectivity, as it uses fired clinker brick, the characteristic material of Brick Expressionism, on the one hand, and is close to Bauhaus and Streamline Modernism in its formal language on the other.

Hans-Sachs-Haus, 1924-1927. Architect: Alfred Fischer. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Hans-Sachs-Haus, 1924-1927. Architect: Alfred Fischer. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Hans-Sachs-Haus, 1924-1927. Architect: Alfred Fischer. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Fischer had already designed the Volkshaus in Gelsenkirchen-Rotthausen between 1919 and 1920, which is still characterized by Expressionist architecture, especially in the design of details such as the lamps and the entrance portal.

The administrative building of the Siedlungsverband Ruhrkohlenbezirk (now RVR) in Essen, built in 1929 according to Fischer’s plans, is a consistent further development of the Hans-Sachs house.

Naming of the Hans-Sachs-Haus

In March 1926, the city announced a competition to find a suitable name for the building that would describe its dual purpose as an office building and cultural center.

A total of 27 names were submitted, of which 26 were shortlisted. Hans-Sachs-Haus won first prize.

Carl von Wedelstaedt, Lord Mayor of Gelsenkirchen, wrote in the commemorative publication for the inauguration of the building in 1927: For us Germans, Hans Sachs is a symbol of the combination of work, which produces material values, and art, to which we owe ideal values. His name was therefore given to the building, which was to become a workplace for trade, commerce and administration and, with its concert hall, a place for the cultivation of the fine arts, especially music.

The name Hans-Sachs-Haus was displayed in capital letters above the main entrance on Ebertstraße. The letters were widely spaced and covered almost the entire facade.

When the name was reinstalled above the main entrance on April 1, 1953, the reconstruction after the destruction of the Second World War was completed. Unlike the original lettering, the letters, illuminated by fluorescent tubes, were much closer together.

The Building

The six-story reinforced concrete skeleton structure is clad with ceramic panels on the first floor. The windows on the first five floors are grouped into bands by cornices.

Hans-Sachs-Haus, 1924-1927. Architect: Alfred Fischer. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Hans-Sachs-Haus, 1924-1927. Architect: Alfred Fischer. Photo: Daniela Christmann

At the back of the strictly structured building with its flat roof, there is a ten-story tower.

Hans-Sachs-Haus, 1924-1927. Architect: Alfred Fischer. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Hans-Sachs-Haus, 1924-1927. Architect: Alfred Fischer. Photo: Daniela Christmann

The multiple recesses in the longitudinal facades are a special feature of the building, which was built over two coal mines to allow the independent components to move freely in relation to each other in the event of subsidence.

In 1927, the Hans-Sachs-Haus contained 5,000 square meters of office space, shops, a hotel with conference rooms and restaurants, a municipal library with a reading room, and a concert hall with 1,500 seats.

Color Coding System

The Hans-Sachs-Haus was the first known example of applied signage (color coding) in a public space.

It was designed by Max Burchartz, a professor of applied art at the Folkwangschule in Essen. The execution was carried out under the direction of Burchartz’s student Anton Stankowski.

The Bauhaus-influenced system, exemplified here by Johannes Itten in color theory and Hinnerk Scheper as color designer and muralist, ran throughout the building with large areas of primary color.

Hans-Sachs-Haus, 1924-1927. Architect: Alfred Fischer. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Hans-Sachs-Haus, 1924-1927. Architect: Alfred Fischer. Photo: Daniela Christmann

It was completely repainted after the Second World War and partially reconstructed in the 1990s. However, this reconstruction was also destroyed in the course of the planned new building.

The entire interior of the building was later demolished and replaced by a new structure. The new building was given a color-coding system based on the original from the 1920s.

War Damage and Reconstruction

During the bombing raids of World War II, many people sought refuge in the basement of the Hans-Sachs-Haus. The building was partially destroyed.

A Schindler paternoster elevator operated in the Hans-Sachs-Haus until 1984.

After severe damage during the Second World War, the Hans-Sachs-Haus was rebuilt from 1947 to 1950 and extended at the end of the 1950s.

From 2009 to 2013, the building was redeveloped according to designs of architects Gerkan, Marg and Partners, preserving the listed brick façade.