Sonnenhof, 1925-1927. Architect: Erwin Gutkind. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Sonnenhof, 1925-1927. Architect: Erwin Gutkind. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Sonnenhof, 1925-1927. Architect: Erwin Gutkind. Photo: Daniela Christmann

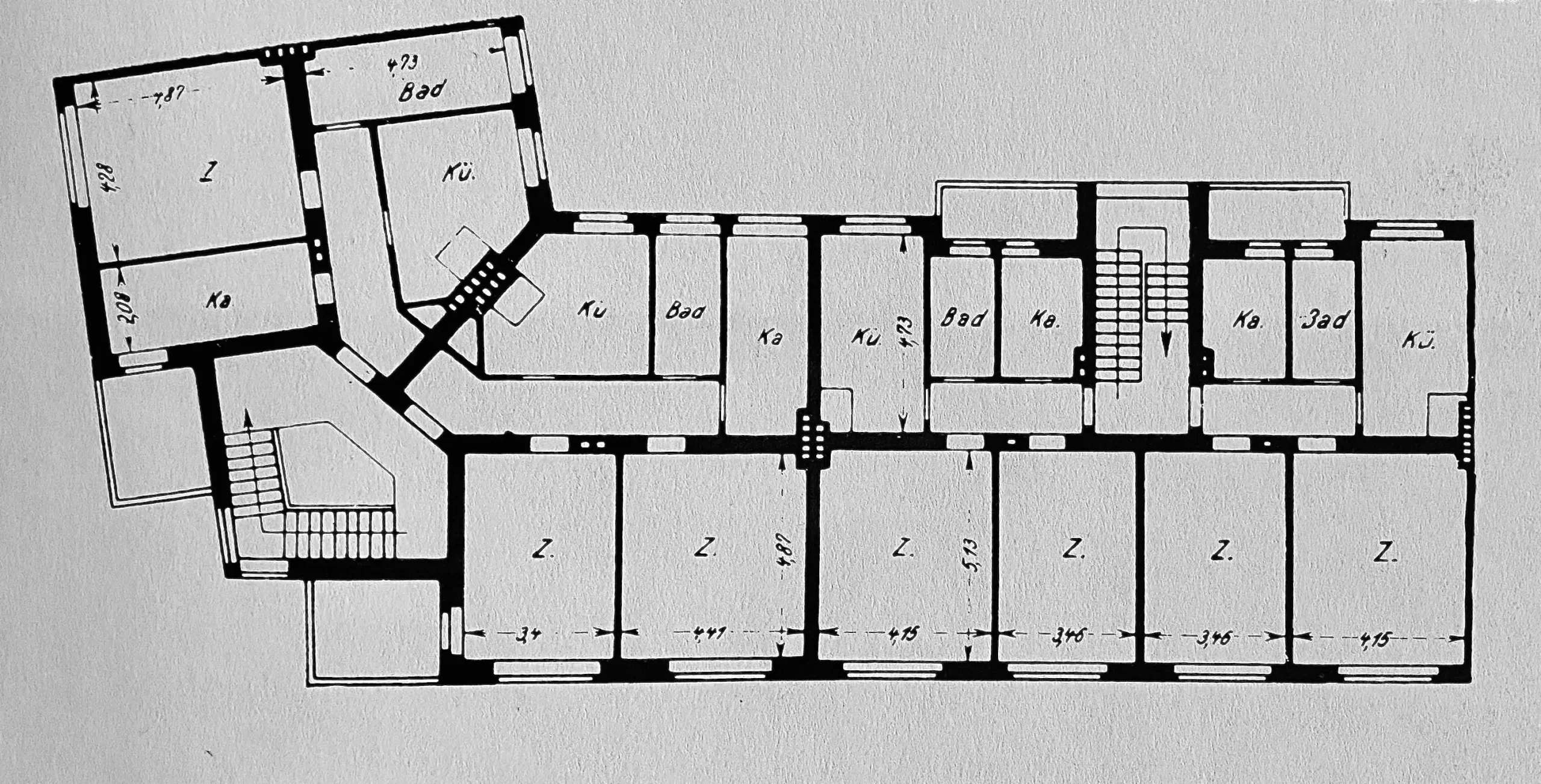

Sonnenhof, 1925-1927. Architect: Erwin Gutkind. Floor plan section

1925 – 1927

Architect: Erwin Gutkind

Archenholdstrasse 56-86, Bietzkestrasse 6-12, Delbrückstrasse 9-15, Marie-Curie-Allee

62-90, Berlin-Friedrichsfelde, Germany

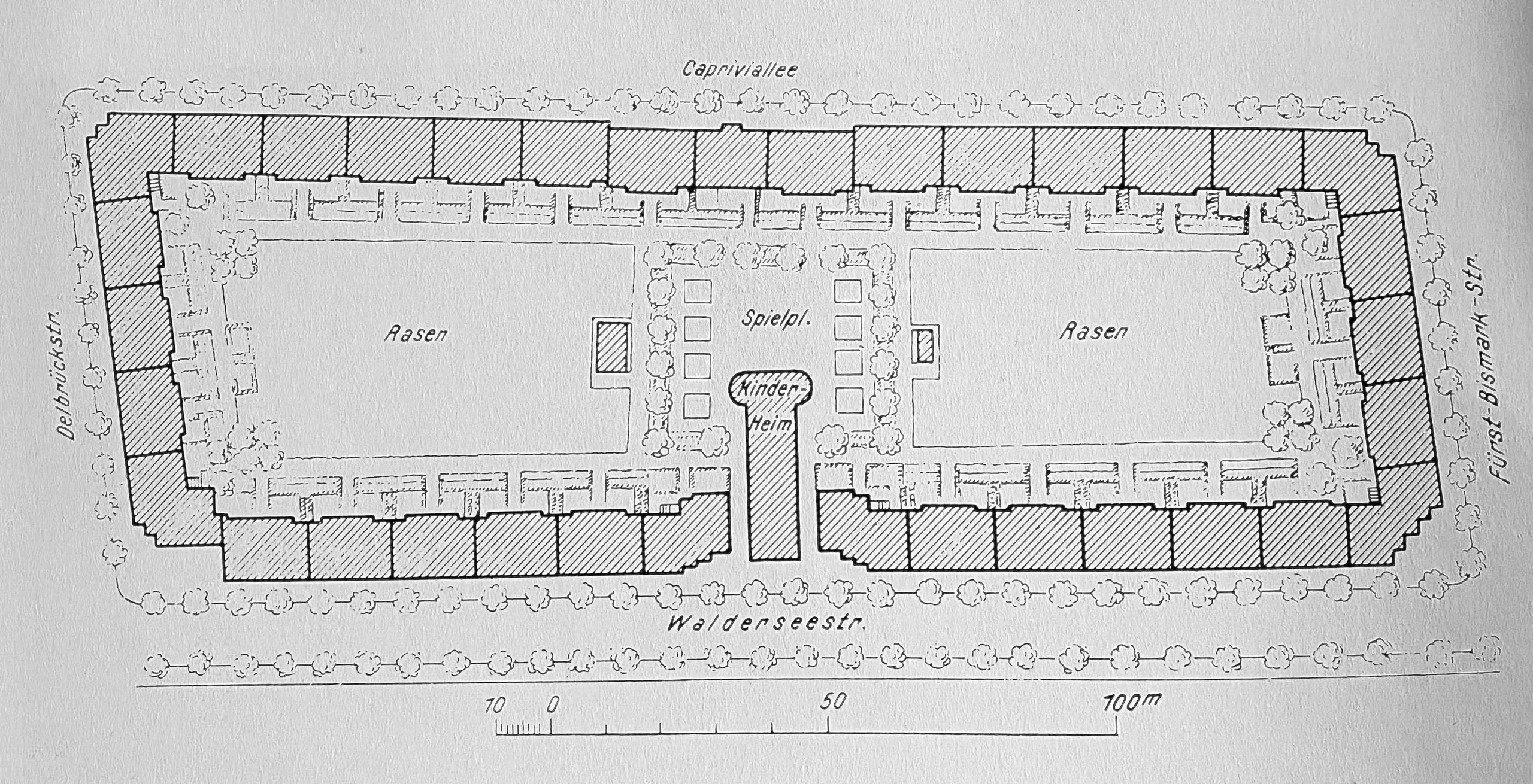

The three- to four-story staggered reinforced concrete buildings of the Sonnenhof residential complex form a closed block on Archenholdstrasse, Delbrückstrasse, Bietzkestrasse and Marie-Curie-Allee in Berlin-Friedrichsfelde.

The developer was Stadt und Land Siedlungsgesellschaft mbH. Originally, the residential block consisted of 266 two-and-a-half room apartments and two shops.

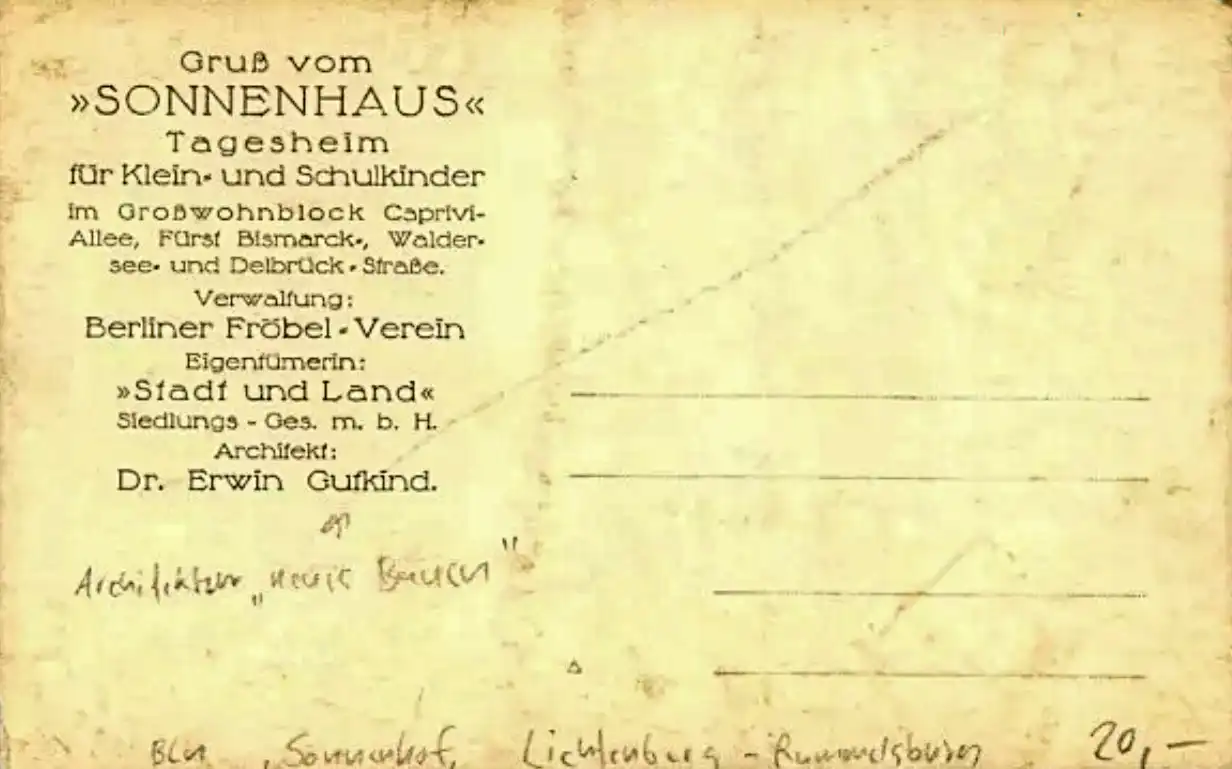

In the courtyard is a daycare center for about fifty children, run by the Berlin Fröbel Association. The gardens were designed by Gustav Allinger and Karl Foerster.

The design of a large, park-like Sonnenhof in conjunction with the construction of a daycare center received national and international press recognition and earned Gutkind a reputation as a socially committed architect.

Sonnenhof, 1925-1927. Architect: Erwin Gutkind. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Sonnenhof. Contemporary Postcard

Sonnenhof. Contemporary Postcard

Sonnenhof, 1925-1927. Architect: Erwin Gutkind. Site plan

Erwin Gutkind

Erwin Anton Gutkind was born into a Jewish family. He studied in Berlin and as an architect and urban planner was a representative of classical modernism.

Gutkind designed the houses on both sides of Heerstrasse in Staaken (Berlin-Spandau), built between 1923 and 1925 as part of the so-called Neu-Jerusalem housing development, as well as the 1926 apartment building on Thule-, Tal-, Hardanger Strasse and Eschengraben on the southern edge of Berlin-Pankow.

Gutkind fled to Paris in 1933 and to London in 1935. His wife, Margarete Jaffé, remained in Berlin and was murdered in Riga in 1942. After the war, Gutkind emigrated to the United States and taught at the University of Pennsylvania.

Berlin Housing Estates

Gutkind’s housing developments in Berlin were built during the post-inflation period. Between 1925 and 1929, the economic boom of the Weimar Republic reached its peak, which was reflected in a veritable building boom.

Whole streets were developed in order to plan uniform residential areas in the suburbs of Berlin. This was made possible by the city’s prudent land policy, which bought up land as the price of land fell due to inflation.

Approximately one-third of Berlin’s total area was thus owned by the city and could be distributed from there.

Building Land Stock

Even before World War I, Berlin had acquired large tracts of land, including the Giesensdorf (now Lichterfelde), Marzahn, and Falkenberg estates as early as 1874.

Tempelhof Field, a former military area, was acquired from the Prussian state, and the city also took over the Dahlem and Ruhleben estates from the state after long negotiations.

Later, in 1924, the former estate districts of Britz, Biesdorf, Marienfelde, Düppel, and Kladow were added to the city in order to keep them out of the hands of land speculators.

In this way, Berlin secured a large amount of building land early on, making the housing developments of the 1920s possible in the first place.

Sonnenhof

Gutkind designed his housing complex around a bright garden courtyard with a day care center and playgrounds.

The exterior facades, with their brick surfaces, emphasize durability and resistance, while the courtyard facades, with their light, bright plaster surfaces and colorful accents, emphasize homeliness.

The balconies open the apartments to the green area and the park.

The concept of a residential complex, especially for families with two working parents, offered new opportunities for living together.

The children were cared for during the day in the day care center that was part of the complex, two shops provided local supplies, and the green inner courtyard offered relaxation after work.

In 1928, the exhibition “Klein-Heim oder Kein Heim – Kleinstwohnungen für Kleinverdiener” (“Small Homes or No Home”), organized by Jakobus Goettel, took place in the Sonnenhof.

Sonnenhof, 1925-1927. Architect: Erwin Gutkind. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Sonnenhof, 1925-1927. Architect: Erwin Gutkind. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Sonnenhof, 1925-1927. Architect: Erwin Gutkind. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Facades and Floor Plans

On the street side, a uniformly structured ribbon facade of alternating layers of plaster, exposed concrete, and clinker unifies the block into a homogeneous overall volume.

The stairwells at the corners of the block give the block a sculptural physicality and connect the sides of the block with continuous concrete rods and clinker bands.

Staircases and balconies divide the courtyard facades.

The apartments have kitchens, bathrooms and bedrooms facing the courtyard, with access to the balconies connected to the staircase. The living rooms and bedrooms face the street.

Sonnenhof, 1925-1927. Architect: Erwin Gutkind. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Sonnenhof, 1925-1927. Architect: Erwin Gutkind. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Sonnenhof, 1925-1927. Architect: Erwin Gutkind. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Sonnenhof, 1925-1927. Architect: Erwin Gutkind. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Sonnenhof, 1925-1927. Architect: Erwin Gutkind. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Design of the Courtyard

The design of the large, park-like courtyard was created by Gustav Allinger and Karl Förster. It is based on the one-story day care center that juts out of the block front in a T-shape and is surrounded by a tree-lined area with playgrounds.

It is bordered on both sides by hedged open spaces. These open spaces are now densely planted with trees.

A perimeter walkway emphasizes the public character of the park areas and separates them from the residential gardens on the opposite side.

In the courtyard was the nursery, a pavilion of double windows and glass doors arranged in a row, with a flat roof of insulated cardboard, the narrow side of which was in the middle of the façade (now much altered).

Three rooms could be extended by sliding walls on rails. One room was intended for movement games or as a bedroom, the others as activity and dining rooms. The three individual rooms could be connected to form a hall for festivities.

Sonnenhof, 1925-1927. Architect: Erwin Gutkind. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Gustav Allinger

Gustav Allinger (1891-1974) was a landscape architect.

In 1920 he designed the main cemetery in Dortmund and in 1924 the expressionist garden “Auf dem Kristallberg”, reminiscent of Bruno Taut’s work, for an exhibition organized by the Association of German Garden Architects.

He won the competition for the Dresden Jubilee Garden Exhibition in 1926 and became its artistic director. In 1927 he was artistic director of the German Horticultural and Silesian Trade Exhibition in Liegnitz (GUGALI).

He became famous for his “Kommender Garten” design for Dresden, a much-discussed ideal of a modern domestic garden.

A supporter of the National Socialists, he joined the NSDAP on April 1, 1933. From 1934 to 1938 he was involved in the planning of the Reich’s highways.

Karl Foerster

Karl Foerster was a botanist and famous for his perennials. In 1903, Karl Foerster founded a perennial nursery on his parents’ property at Ahornallee 32 in Berlin-Westend.

From 1910 to 1911, he moved the nursery to Bornim near Potsdam. There, Foerster transformed a 5,000-square-meter plot of farmland into a garden, the Karl Foerster Garden, with a sunken garden, a rockery, an autumn bed, and a spring path.

The garden is stylistically influenced by Willy Lange. It was redesigned by Hermann Mattern in the 1930s and restored or reconstructed several times by Hermann Göritz in the second half of the 20th century.

Reconstruction of the Sonnenhof

Between 1972 and 1973, as part of the GDR‘s modernization program, the residential complex was expanded by adding floors to the attic, increasing the number of apartments from the original 260 to 333.