1920 – 1924

Architect: Peter Behrens

Brüningstrasse 50, Frankfurt am Main-Höchst

The former Technical Administration Building of Farbwerke Hoechst AG is an expressionist office building on the site of the former Farbwerke Hoechst AG in the Höchst district of Frankfurt.

It was completed between 1920 and 1924 according to designs by architect Peter Behrens.

A part of the building was used in stylized form as Hoechst AG’s company logo Tower and Bridge from 1947 to 1997.

The listed building complex consists of two three-story administrative wings and a prestigious entrance area, which are connected via a bridge to the Executive Board building erected in 1892.

Behrens Building, 1920-1924. Architect: Peter Behrens. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Behrens Building, 1920-1924. Architect: Peter Behrens. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Background

In June 1920, the Board of Management of Farbwerke Hoechst, under General Manager Adolf Haeuser, decided to consolidate the technical departments, which had been scattered throughout the Höchst plant until then, in a prestigious new building.

A site opposite the existing Board of Management building was chosen for the new administration building, which was to have a facade at least 150 meters long.

On August 21, 1920, the request for the planning of the new administration building was sent to the Berlin architect Peter Behrens, who promptly prepared the first drafts.

On September 14, 1920, the contract for the new technical office building of Farbwerke vorm. Meister, Lucius & Brüning in Höchst am Main’ was signed by Behrens.

Demolition of the existing buildings on the site began in January 1921.

By the end of 1921, the shell of the building was largely completed.

However, a shortage of building materials during the inflationary years and the occupation of the site by French troops in May 1923 delayed completion of the building.

It was not until April 1924, after the introduction of the Rentenmark, that construction work continued.

The ceremonial opening of the new building took place on June 6, 1924.

Brick Expressionism

Style-wise, the administration building can be assigned to brick expressionism.

The crystal motifs typical of Expressionism are found as ornaments in the arrangement of the bricks on the floor and walls as well as in the windows and lamps.

In the design of the stained glass windows, there are echoes of works by the De Stijl group of artists.

The architect had many components such as door handles, railings and individual windows made by hand. This is due to the importance and high value that Behrens attached to craftsmanship.

In the design of the building, Behrens made explicit references to Farbwerke Höchst:

The expressive colorfulness of the bricks, dyed with the client’s colors, refers to the product range of up to 30,000 color shades that were produced at the Farbwerke and shipped all over the world.

The crystal-shaped motifs are reminiscent of the outlines of the crystals of penicillin sodium, which could be made visible under the microscope in the Höchst laboratories.

Behrens Building, 1920-1924. Architect: Peter Behrens. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Behrens Building, 1920-1924. Architect: Peter Behrens. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Behrens Building, 1920-1924. Architect: Peter Behrens. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Building and Facades

For cost reasons and in contrast to the Executive Board building opposite, Behrens designed the Technical Administration Building entirely in brick.

Bricks in different colors divide the 185-meter-long facade of the administration building into three sections.

An upwardly tapering base with square windows characterizes the two office wings, which converge at an obtuse angle in the entrance building due to the course of the road.

Two rows of vertical windows divide the floors located above. The facade is terminated on the uppermost floors by parabolic windows.

Bridge and Tower

Bridge and tower are defining elements of the new building, in the central part of which the main entrance and the reception hall are located.

The facade of the central section is accentuated by a striking tower with parabolic sound openings for the carillon and a clock with an expressive dial.

Sounds from Richard Wagner‘s Parsifal were intended to signal the change of shift to the workers at the Farbwerke.

Despite the fact that bells were already in place, the carillon in the tower was never completed for cost reasons.

A brick arched bridge, which takes up the parabola motif of the windows on the upper floors, spans between the tower and the boardroom building.

Behrens Building, 1920-1924. Architect: Peter Behrens. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Main Entrance

The three-door main entrance in the central building has a restrained design.

Two lions carved in stone and enthroned above the doors represent the company emblem of Meister, Lucius & Brüning, the company from which the Farbwerke emerged.

Interior

The representative, fifteen-meter-high atrium with side staircases occupies the entire height of the central building and is illuminated by large skylights.

Brick colors become progressively lighter from the floor to the glass domes, while at the same time the mass and number of bricks increases.

Similarly, the arrangement of the light and dark bricks of the stairways echo the geometry and rhythm of the hall walls, as do the upward tapering height of the circulating corridors and the increasingly narrow window formats.

Behrens Building, 1920-1924. Architect: Peter Behrens. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Behrens Building, 1920-1924. Architect: Peter Behrens. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Behrens Building, 1920-1924. Architect: Peter Behrens. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Showroom

Opposite the main entrance is the former showroom, where visitors were presented with the Farbwerke product range in display cases.

The room’s seven-meter-high ceiling is supported by six columns and lit by colored glazed windows on three sides.

In the 1930s, the room was converted into a memorial to employees who died in World War I. In 1938, it housed the plant’s telephone exchange and, since the 1960s, storage and conference rooms.

The statue of a worker created by Richard Scheibe remained the only surviving work of art.

Behrens Building, 1920-1924. Architect: Peter Behrens. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Behrens Building, 1920-1924. Architect: Peter Behrens. Photo: Daniela Christmann

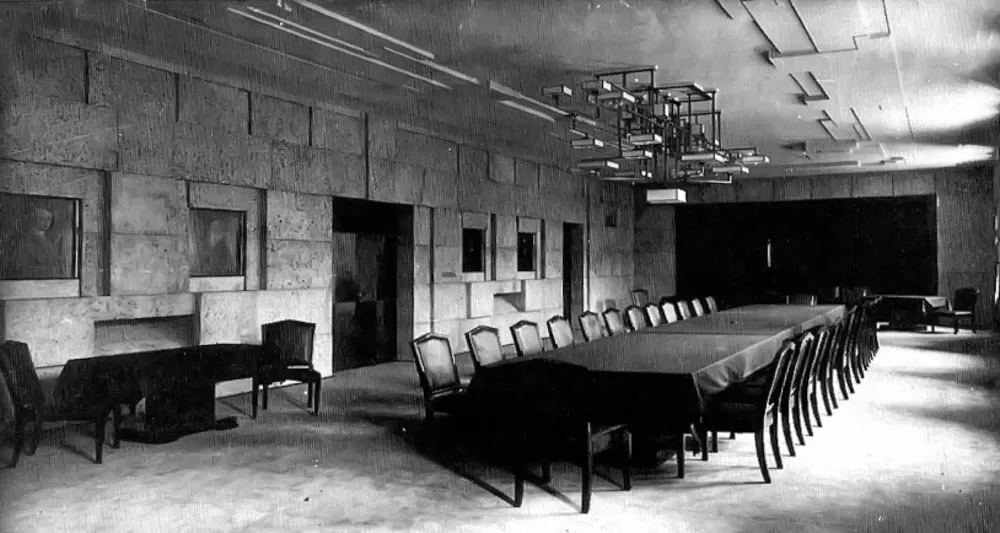

Marble Hall and Lecture Hall

On the second floor above the main entrance was the so-called Marble Hall. The former meeting room owed its name to the travertine wall covering, which resembled marble.

A special feature was the room-determining chandelier designed by Behrens, of which only blueprints and photos exist today. A portal to the bridge connected the room directly to the boardroom building opposite.

Opposite the marble hall at the rear of the building was the two-story lecture hall of the Behrens Building.

The original hall had elaborate wood paneling; only the large table with lectern was made of brick to allow for the demonstration of chemical experiments.

The lecture hall burned out during World War II and was rebuilt in 1951 in the style of that time.

Behrens Building, 1920-1924. Architect: Peter Behrens. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Behrens Building, 1920-1924. Architect: Peter Behrens. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Behrens Building, 1920-1924. Architect: Peter Behrens. Photo: Daniela Christmann

I.G. Farben

On November 12, 1925, the Farbwerke merged with other chemical companies to form I.G. Farbenindustrie AG.

Five years later, the administration of what was then the world’s fourth-largest company moved to the new I.G. Farben building in Frankfurt’s Westend district, which was built by Hans Poelzig.

In the years that followed, the Höchst site became increasingly less relevant.

The interior of the administration building underwent numerous renovations in the 1930s. The adjoining rooms of the large exhibition hall were converted into the plant’s telephone exchange and storage rooms. The large meeting rooms on the first and second floors were divided into smaller offices.

The Höchst plant survived World War II largely undamaged. In June 1940, bombs hit during an air raid, devastating the auditorium in the north of the building.

Behrens Building, 1920-1924. Architect: Peter Behrens. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Behrens Building, 1920-1924. Architect: Peter Behrens. Photo: Daniela Christmann

After 1945

I.G. Farben was released from Allied control in June 1952.

The company went into liquidation and was divided into eleven successor companies, including Farbwerke Hoechst AG.

In 1954, Brüningstrasse was closed to public traffic.

In 1965, all buildings were given new names within the company. The Behrensbau became the headquarters of the Human Resources Department as Building C 770.

In 1994, the conversion of Hoechst AG into a holding company began. Since January 1, 1998, the Behrensbau has belonged to Infraserv GmbH & Co. Höchst KG, which was spun off from Hoechst AG as the operator of Industriepark Höchst.

Renovation and Restoration

In 1998, a comprehensive renovation of the Behrens Building began. The facade was cleaned and repaired, and all the windows and building services were replaced.

The offices were largely modernized. Floors, corridors, galleries and courtyards largely correspond to the original condition.

Natural aging and color loss had caused the domed hall to become darker. In coordination with the monument preservation authorities, the colored surfaces were cleaned and carefully retouched in those areas where no old layers of paint remained.

The restoration was completed in 2002. In 2005, the auditorium and the marble hall on the second floor were renovated. The original building fabric, which had disappeared behind wooden panelling, was largely uncovered.

In 2007, the renovation of the exhibition hall, which had been heavily altered by reconstruction work, was completed.

Current Use

The Behrensbau is now the headquarters of Infraserv Höchst’s management and the Hoechster Pension Fund.

The building is not open to the public, but guided tours are available.