1928-1930

Architect: Ludwig Mies van der Rohe; Interior Design: Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Lilly Reich; Garden Design: Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Grete Roder

Černopolní, 45, Brno, Czech Republic

On behalf of the clients Fritz and Grete Tugendhat, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe designed the Villa Tugendhat between 1928 and 1930 as a residence for the family. The interior was designed together with his partner Lilly Reich.

Tugendhat House, 1928-1930. Architect: Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Tugendhat House, 1928-1930. Architect: Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Tugendhat House, 1928-1930. Architect: Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Tugendhat House, 1928-1930. Architect: Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. Photo: Daniela Christmann

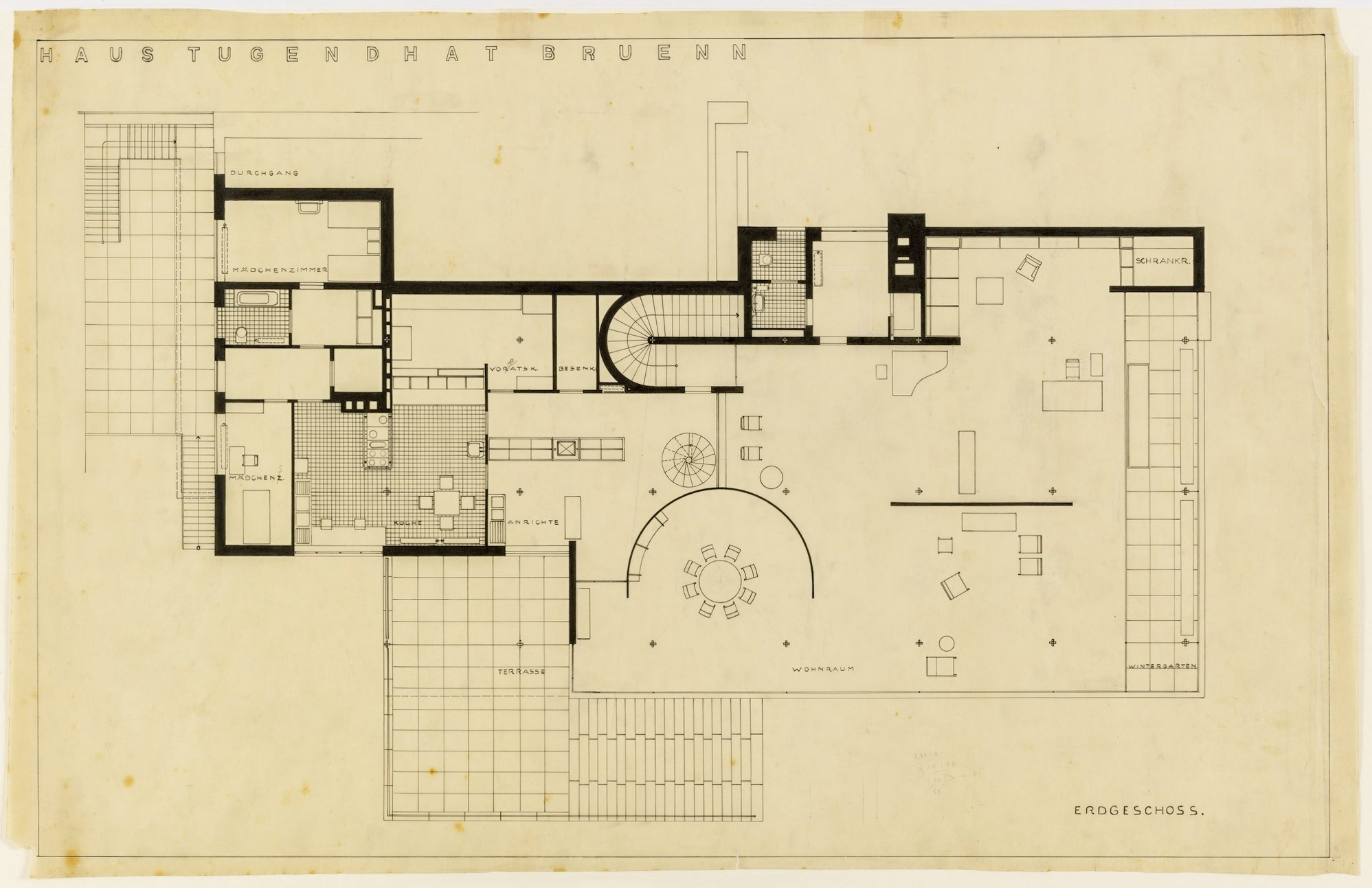

Mies van der Rohe, Tugendhat House. Ground floor plan drawing. Ink and pencil on tracing paper, 62.2 x 97.8 cm, Collection Museum of Modern Art, New York. https://www.moma.org/collection/works/89535

Grete and Fritz Tugendhat

On the occasion of her marriage to Fritz Tugendhat, Grete Tugendhat (divorced Weiss, née Löw-Beer) received a two thousand square meter section of the park on her parents’ property as a dowry from her parents, as well as the costs of building a house.

The parents of the bride and groom, Marianne and Alfred Löw-Beer, belonged to a large Jewish family that had contributed significantly to the industrialization of Czechoslovakia with textile, sugar and cement factories in Brno, Moravia.

Their daughter Grete (1903-1970) was born in 1903. Growing up in an upper bourgeois environment, she married the Silesian industrialist Hans Weiss in 1922. Their daughter Hanna was born in 1924 and they divorced a few years later.

In 1928, she married Fritz Tugendhat (1895-1958). At the time, he ran his father’s cloth factory, was eight years older than Grete and, like her, came from a Jewish family in Brno.

Both house and property were advance payments for her inheritance, as Grete Tugendhat, unlike her two brothers, did not have a stake in her parents’ Löw-Beer family factories.

Tugendhat House, 1928-1930. Architect: Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Tugendhat House, 1928-1930. Architect: Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Tugendhat House, 1928-1930. Architect: Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Tugendhat House, 1928-1930. Architect: Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Meeting Ludwig Mies van der Rohe

From 1924 to 1928, Grete Tugendhat lived in Berlin, initially with her first husband and then with her daughter, for a total of four years.

She moved in the circles of art historian Eduard Fuchs and in 1927 met Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, the architect of the Perls House built in 1911 at Hermannstrasse 14 in Berlin-Zehlendorf, which Eduard Fuchs had bought.

Mies van der Rohe had originally designed the house for the lawyer, art collector and dealer Hugo Perls.

In 1918, Perls sold it to the cultural scientist, art collector and patron Eduard Fuchs – allegedly for five works by Max Liebermann. In 1928, Eduard Fuchs had a gallery extension built according to plans by Mies van der Rohe.

Shortly after their wedding, Grete and Fritz Tugendhat visited Villa Kempner in Berlin-Charlottendorf, which was built by Mies van der Rohe between 1921 and 1923 and has since been destroyed. In mid-1928, the couple had their first get-together with architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe.

Designs for the house in Brno

In September 1928, Mies van der Rohe traveled to Brno for the first time.

In a lecture in Brno in January 1969, Grete Tugendhat recalled:

“The Weissenhof Estate made a great impression on me at that time. I had always wanted a modern, spacious house with clear, simple forms, and my husband was horrified by the rooms of his childhood, which were crammed with countless knick-knacks and doilies. So when we decided to build a house, we called Mies van der Rohe for a consultation. …

He said, for example, that you can never calculate the ideal dimensions of a room, that you have to feel a room when you stand in it and move around in it, that you should never build a house from the façade, but from the inside out, that windows should no longer be holes in the wall, but a surface stretched between the floor and ceiling and as such a structural element. …

Then we noticed (on the floor plan) little crosses about five meters apart. We asked: “What is that?” To which Mies replied quite naturally: “Those are the iron supports that carry the building. At that time, no private house had ever been built with iron framework, so it was no wonder that we were very surprised. …

There were many things done here for the first time that are taken for granted today without knowing where they came from. …

Tugendhat House, 1928-1930. Architect: Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Tugendhat House, 1928-1930. Architect: Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Materials Ludwig Mies van der Rohe

He then explained to us how important the use of fine materials was in modern, so to speak unadorned and unornamental building and how this had been neglected until then, for example by Le Corbusier. …

As the son of a stonemason, Mies was familiar with beautiful stone from childhood and had a special love for it. He spent a long time searching for a particularly beautiful block of onyx in the Atlas Mountains and closely supervised the sawing and joining of the slabs himself to ensure that the design of the stone came out correctly. …

We probably did not fully understand what an unusual amount of work the construction meant for Mies, as he designed every detail himself, right down to the door handles. …

The seating was all made of chrome-plated steel. For the dining room we had 24 of the armchairs, now called Brno chairs, covered in white parchment; in front of the onyx wall there were two armchairs, now called Tugendhats, covered in silver-grey Rodier fabric and two Barcelona armchairs covered in emerald-green leather.

In front of the large glass wall was a deck chair with ruby red velvet upholstery. Mies van der Rohe tried out all these color combinations on site for a long time together with Mrs. Lilly Reich.”

Tugendhat House, 1928-1930. Architect: Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Tugendhat House, 1928-1930. Architect: Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Tugendhat House

Built between 1929 and 1930, the villa was inhabited by the Fritz and Greta Tugendhat family from 1930 until their emigration in 1938.

Located on a slope, the property was accessed from Černopolní Street (then Schwarzfeld Street).

Mies van der Rohe designed a residential building in steel skeleton construction with three floors offset from each other.

Tugendhat House, 1928-1930. Architect: Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Tugendhat House, 1928-1930. Architect: Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Tugendhat House, 1928-1930. Architect: Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Layout

Access is on the upper floor, which also housed the bedrooms, bathrooms, the nanny’s apartment, a play area and a terrace.

A spiral staircase leads to the middle floor, which houses the large open-plan living area consisting of a living room and conservatory covering an area of 280 square meters, as well as the kitchen and another terrace. The area opens up completely to the garden through floor-to-ceiling glass panes.

Utility and storage rooms are located on the lower floor.

Similar to Mies’ Barcelona Pavilion, the house has a flowing space with an open floor plan and load-bearing columns instead of solid walls.

Two of the large window panes on the main floor facing the park can be lowered completely using chain drives in the basement. The main floor and the adjoining conservatory corridor along the south façade are air-conditioned via an air heating system.

The huge circulation chambers of the complex system are located in the utility rooms on the slope side of the basement. The supply air was cleaned with an oil filter and flavored with wood chips.

Tugendhat House, 1928-1930. Architect: Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Tugendhat House, 1928-1930. Architect: Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Tugendhat House, 1928-1930. Architect: Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Tugendhat House, 1928-1930. Architect: Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Tugendhat House, 1928-1930. Architect: Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Tugendhat House, 1928-1930. Architect: Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Tugendhat House, 1928-1930. Architect: Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Tugendhat House, 1928-1930. Architect: Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Interior design

Generous glazing integrates the outdoor space with its trees and lawns to create a kind of scenic foil that is perceived as a visual boundary to the interior.

By lowering the almost five-meter-long glass elements, the interior and exterior areas merge almost completely into one another.

With his choice of a pale, muted color palette and the black and white of the materials marble, wood, silk and leather, Mies sought to create a contrast to the colors of nature.

Cross-shaped steel supports arranged at regular intervals and clad in chrome-plated sheet metal form the structural system.

The free-standing wall made of translucent onyx marble has no static function, but serves to separate the working and reading area from the living area.

The veneer of the wooden screen cladding in the dining area was made from Macassar ebony. The semi-circular partition wall had been thought to have disappeared since 1940, but was reconstructed in the 1980s.

In 2011, the original veneer panels were rediscovered as wall cladding in the refectory of the University of Brno. The wall has since been reconstructed a second time using the original panels.

Tugendhat House, 1928-1930. Architect: Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Tugendhat House, 1928-1930. Architect: Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Tugendhat House, 1928-1930. Architect: Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Furnishings

Room-high doors, cupboards, shelves and desks are made of rosewood. Floors, stairs and window sills are made of travertine, curtains of black and beige Schantung silk.

The floor of the main room was laid with ivory-white linoleum and the living area was bordered by a square, Berber-like carpet made of natural wool by the Lübeck workshop Alen Müller-Hellwigs.

A bust of Wilhelm Lehmbruck placed on a plinth served as a focal point.

Is the Tugendhat house a place to live?

In 1930, their first son Ernst was born and the family moved into the newly built house at the end of the year.

” Is it possible to live in the Tugendhat House?” This question from architecture critic Justus Bier sparked a discussion about the habitability of the house in 1931, shortly after the house was completed and published in the magazine of the Deutscher Werkbund “Die Form”.

At the time, both the owners Grete and Fritz Tugendhat and various critics, including the architect Ludwig Hilberseimer, commented on the question “Habitable house or work of art?”.

“No photograph of this house can convey a true impression. You have to move in the space of the house – its rhythm is like music,” enthused Hilberseimer after visiting the newly built villa.

Fate of the house during the Nazi regime

From 1930 to 1938, the Tugendhat family lived in the house. Due to their Jewish origins, they first had to flee to Switzerland and later to Venezuela.

In 1939, Brno was occupied by the Nazi regime and belonged to the Reich Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia until 1945. During the German occupation, the commercial director of a branch of the Klöckner-Werke resided in the requisitioned building.

Walter Messerschmidt and his family lived in the house from June 1943. The Messerschmidts found the large living space too uncomfortable, had it partitioned off and set up a farmhouse parlor in it.

After the installation of solid partition walls, the house also served as a design office for the Ostmark aircraft engine factory.

Post-war period

Following the liberation of Czechoslovakia in 1945, the building was used by the Red Army.

From the early 1950s, the building served as a school and therapy center before it was taken over and renovated by the Brno City Council in the 1980s.

In 1992, Villa Tugendhat hosted the summit meeting at which the treaty on the division of Czechoslovakia was signed.

By a decision of the Brno City Council, the villa was handed over to the Brno City Museum for use and has been open to the public as a monument of modern architecture in Brno since July 1, 1994.

World cultural heritage

Due to its exceptional artistic value, the Tugendhat House was declared a National Cultural Monument in August 1995.

In 2001, UNESCO declared the building a World Heritage Site. It has been extensively restored since 2010 and has been open to the public since March 2012.