1923 – 1924

Architects: Gerrit Rietveld, Truus Schröder-Schräder

Prins Hendriklaan 50, Utrecht, Netherlands

The Rietveld Schröder House in Utrecht, the Netherlands, is a residential building built in 1924 by architect Gerrit Rietveld for Truus Schröder-Schräder.

Rietveld Schröder House, 1923-1924. Architects: Gerrit Rietveld, Truus Schröder-Schräder. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Rietveld Schröder House, 1923-1924. Architects: Gerrit Rietveld, Truus Schröder-Schräder. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Icon

The small detached house, with its flexible room layout and its visual and formal qualities, was a manifesto of the ideals of the Dutch artist and architect group De Stijl in the 1920s and has since been considered one of the icons of modern architecture.

The house is unique in many ways. It is the only building of its kind in Rietveld’s oeuvre and also differs from other important early modern buildings such as Le Corbusier‘s Villa Savoye or Mies van der Rohe’s Tugendhat House.

The difference lies primarily in the treatment of the architectural space and the conception of the building’s functions.

The quality of the Rietveld-Schröder House lies in the fact that it represents a synthesis of the design concepts of modern architecture at a certain point in time.

Rietveld Schröder House, 1923-1924. Architects: Gerrit Rietveld, Truus Schröder-Schräder. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Rietveld Schröder House, 1923-1924. Architects: Gerrit Rietveld, Truus Schröder-Schräder. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Rietveld Schröder House, 1923-1924. Architects: Gerrit Rietveld, Truus Schröder-Schräder. Photo: Daniela Christmann

De Stijl

De Stijl, Dutch for “The Style,” was a Dutch group of painters, architects, and designers who founded an artists’ association and art magazine of the same name in Leiden in 1917.

The founding members were the painter and art theorist Theo van Doesburg, the painters Piet Mondrian and Georges Vantongerloo, the architects Robert van ‘t Hoff, J.J.P. Oud, and Jan Wils, the painters Vilmos Huszár and Bart van der Leck, and the poet Antony Kok.

By 1922, eight of the original ten members had left the group, but new members joined, including the architects Gerrit Rietveld (1918), Cornelis van Eesteren (1922), and the painter Friedrich Vordemberge-Gildewart (1924).

De Stijl saw itself less as a group than as a forum for artists who shared similar ideas and goals in art, and who aimed for joint exhibitions and publications.

Principles

The members of De Stijl were committed to a geometric-abstract style of representation in art and architecture and to a purism limited to functionality, which, similar to the German Bauhaus, with which it is closely associated in terms of ideas and art history, established principles for an aesthetic applicable to all areas of design.

The group’s goal was to completely abandon the representational principles of traditional art and to develop a new, completely abstract formal language based on variations of a few elementary pictorial design principles (horizontal/vertical, large/small, light/dark, and primary colors).

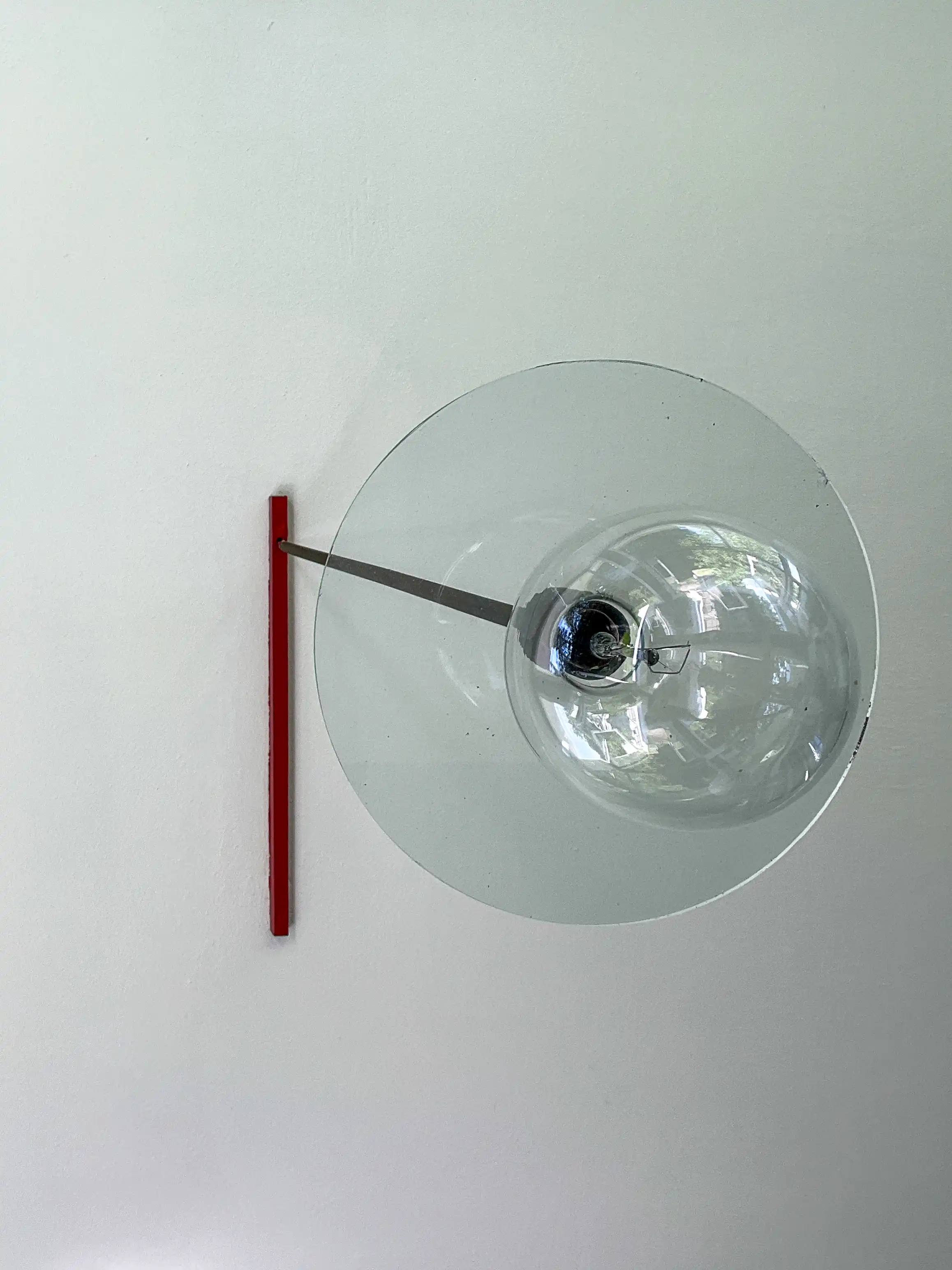

This meant a reduction of colors to the three primary colors red, yellow, and blue, and the non-colors black, gray, and white. De Stijl’s concepts not only influenced the visual arts and architecture, but also the design of furniture and other everyday objects.

Rietveld Schröder House, 1923-1924. Architects: Gerrit Rietveld, Truus Schröder-Schräder. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Rietveld Schröder House, 1923-1924. Architects: Gerrit Rietveld, Truus Schröder-Schräder. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Rietveld Schröder House, 1923-1924. Architects: Gerrit Rietveld, Truus Schröder-Schräder. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Rietveld Schröder House

Gerrit Rietveld designed this house in close collaboration with the client, Truus Schröder-Schräder. After the death of her husband in 1923, she wanted to leave Utrecht and move near her sister in Amsterdam.

She asked Rietveld to help her find a new home for herself and her three children – but when no suitable house could be found, he suggested a completely new building.

Finally, a suitable property was found in the Prins Hendriklaan (number 50) on the outskirts of Utrecht, with an unobstructed view of the polder landscape.

For both of them, the house was an opportunity, an experiment, a clarification of the question: “How do you want to live? Schröder’s numerous notes on the design of the house and articles on the new architectural developments of the time have been preserved.

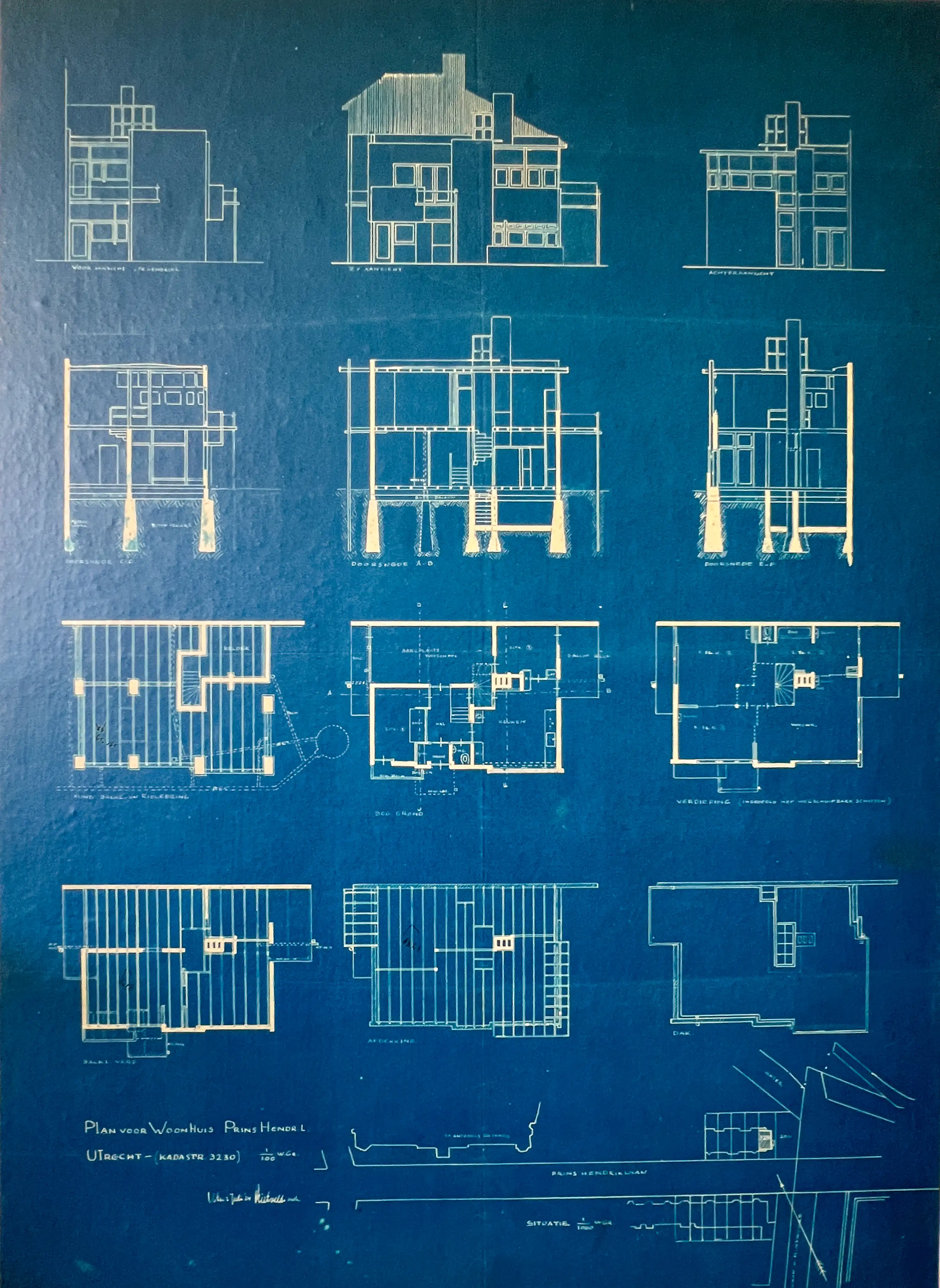

Rietveld Schröder House, 1923-1924. Architects: Gerrit Rietveld, Truus Schröder-Schräder. Plans

Rietveld Schröder House, 1923-1924. Architects: Gerrit Rietveld, Truus Schröder-Schräder. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Rietveld Schröder House, 1923-1924. Architects: Gerrit Rietveld, Truus Schröder-Schräder. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Rietveld Schröder House, 1923-1924. Architects: Gerrit Rietveld, Truus Schröder-Schräder. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Rietveld Schröder House, 1923-1924. Architects: Gerrit Rietveld, Truus Schröder-Schräder. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Rietveld Schröder House, 1923-1924. Architects: Gerrit Rietveld, Truus Schröder-Schräder. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Rietveld Schröder House, 1923-1924. Architects: Gerrit Rietveld, Truus Schröder-Schräder. Photo: Daniela Christmann

The client Truus Schröder

The client Truus Schröder chose a site on the outskirts of the city that was close to nature and wanted large windows that offered a view of the surroundings. However, she wanted to protect her privacy from prying eyes. As a result, the apartment was located on the top floor, which did not correspond to the usual Dutch house typology at the time.

The interior was to reflect her idea of family life: “You see, I had left my husband three times because I disagreed so much with him about the upbringing of the children. They were looked after by a maid, but I thought it was terrible for them.

After my husband died, I had full custody of the children and thought a lot about how we could live together. When Rietveld made a sketch of the rooms, I asked him: “Can these walls be removed?” He replied: “With pleasure, let’s take these walls out!” (…) That’s how the large room was created.” (Truus Schröder, from Alice Friedman: Women and the Making of the Modern House: A Social and Architectural History, p. 76)

Portrait Truus Schröder-Schräder

Rietveld Schröder House, 1923-1924. Architects: Gerrit Rietveld, Truus Schröder-Schräder. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Flexible Spaces

After the walls were removed, Truus Schröder considered partitioning off individual areas at certain times. Rietveld resisted at first, but then realized the children’s rooms as small, self-contained units. They were arranged along the facades and could be integrated into the common living area.

The furniture was designed with spatial flexibility in mind. The beds in the small rooms doubled as sofas in the living room. The wardrobes were used to furnish the bedrooms and also concealed the folding walls.

The fixed elements (staircase, toilet, bathroom, wardrobe and fireplace) formed a lighted center around which the variable rooms were grouped.

Rietveld convinced her to use red, blue and yellow with white and black for the new house to emphasize space and movement.

Rietveld Schröder House, 1923-1924. Architects: Gerrit Rietveld, Truus Schröder-Schräder. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Rietveld Schröder House, 1923-1924. Architects: Gerrit Rietveld, Truus Schröder-Schräder. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Rietveld Schröder House, 1923-1924. Architects: Gerrit Rietveld, Truus Schröder-Schräder. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Rietveld Schröder House, 1923-1924. Architects: Gerrit Rietveld, Truus Schröder-Schräder. Photo: Daniela Christmann

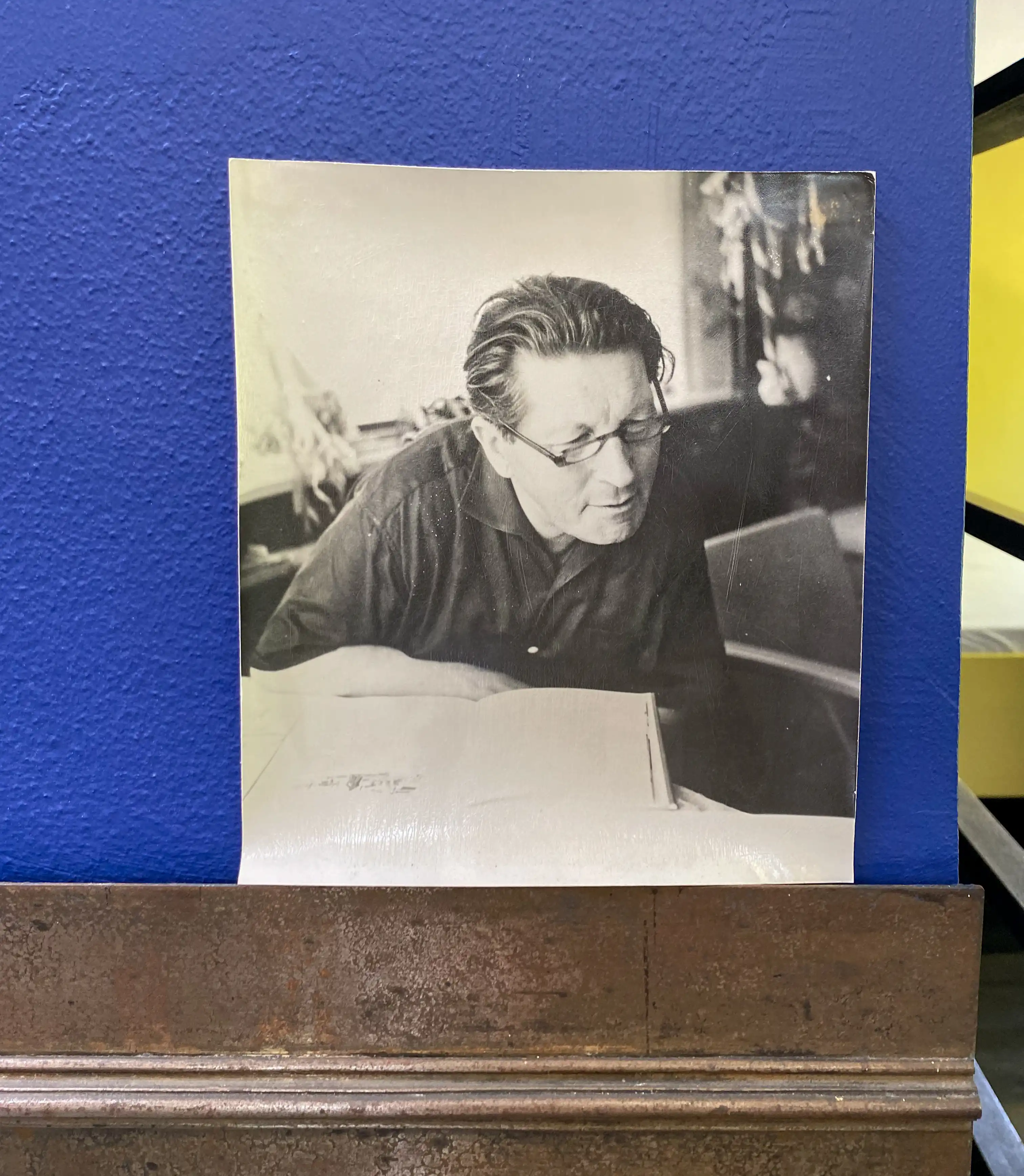

Gerrit Rietveld

Neither Rietveld nor Schröder had done anything like this before. Gerrit Rietveld, the son of a cabinetmaker, had worked as a furniture designer for the architect Robert van ‘t Hoff between 1914 and 1919.

Until then, he had not built any houses of his own. In 1926, El Lissitzky described his approach: “He is not a scholar of architecture, but a carpenter who does not know how to draw plans routinely. He does everything with models, feels things with his hands, and therefore his product is not abstract.

Rietveld was married in 1923, when he designed the Rietveld Schröder House, and had six children. A widower, he moved into the Schröder house in 1957 and lived there until his death in 1964. From 1924 to 1933, he had an architectural office on the first floor of the house.

Portrait Gerrit Rietveld

Rietveld Schröder House, 1923-1924. Architects: Gerrit Rietveld, Truus Schröder-Schräder. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Building Application

Since the building differed greatly from the architectural style of the surrounding area, Rietveld had to use a few tricks to get the building application approved. For example, it was not clear from the submitted floor plans that the rooms on the upper floor would be separated by sliding walls.

In the side view, the roof line of the building behind is so clearly visible that it gives the impression that the Schröder house also has a pitched roof. Because of these inaccuracies in the plans, the building permit was granted without further conditions.

Construction

The building, originally planned as a concrete structure, was finally built in plastered masonry for cost reasons. Only the foundations and the balconies were made of reinforced concrete.

Rietveld was often found on the building site, partly because he specified many details during the construction phase, and partly because the workers were sometimes overwhelmed by the new forms and ideas in his absence.

Use

The client Truus Schröder lived in the building until her death in 1985.

Since then, the building has been open to the public as part of the Centraal Museum Utrecht. Guided tours are available for groups of up to 12 people. Booking is required.

Restoration

The Rietveld Schröderhuis was used as a private residence for sixty years, with a number of changes made to accommodate its changing uses. In the 1970s and 1980s, the Rietveld Schröderhuis was restored to its original 1920s condition by Bertus Mulder, one of Rietveld’s assistants.

The restoration work in the 1970s and 1980s was carried out with great care, trying to preserve as much as possible. All the original furniture was restored and repositioned as it was in the 1920s. Missing items were reconstructed from records and existing documents.

Unfortunately, due to the poor condition of some of the materials, the plaster and some of the furnishings had to be replaced.

UNESCO World Heritage Site

The house has been a UNESCO World Heritage Site since November 2000.