1922

Design: Carl Krayl

Otto-Richter-Straße, Magdeburg

At the suggestion of city planning officer Bruno Taut, and based on designs by architect Carl Krayl, the plaster facades of the buildings on Otto-Richter-Straße in Magdeburg were painted in 1922.

During the street’s renovation around the turn of the millennium, the original color scheme was reconstructed based on a few color samples.

Only a black-and-white photograph of the façade of house no. 2 with jagged and curved lines on a strong ultramarine blue background has been preserved.

Facade painting on Otto-Richter-Straße in Magdeburg. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Facade painting on Otto-Richter-Straße in Magdeburg. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Residential building at Otto-Richter-Straße 2, 1922. Colour design: Carl Krayl

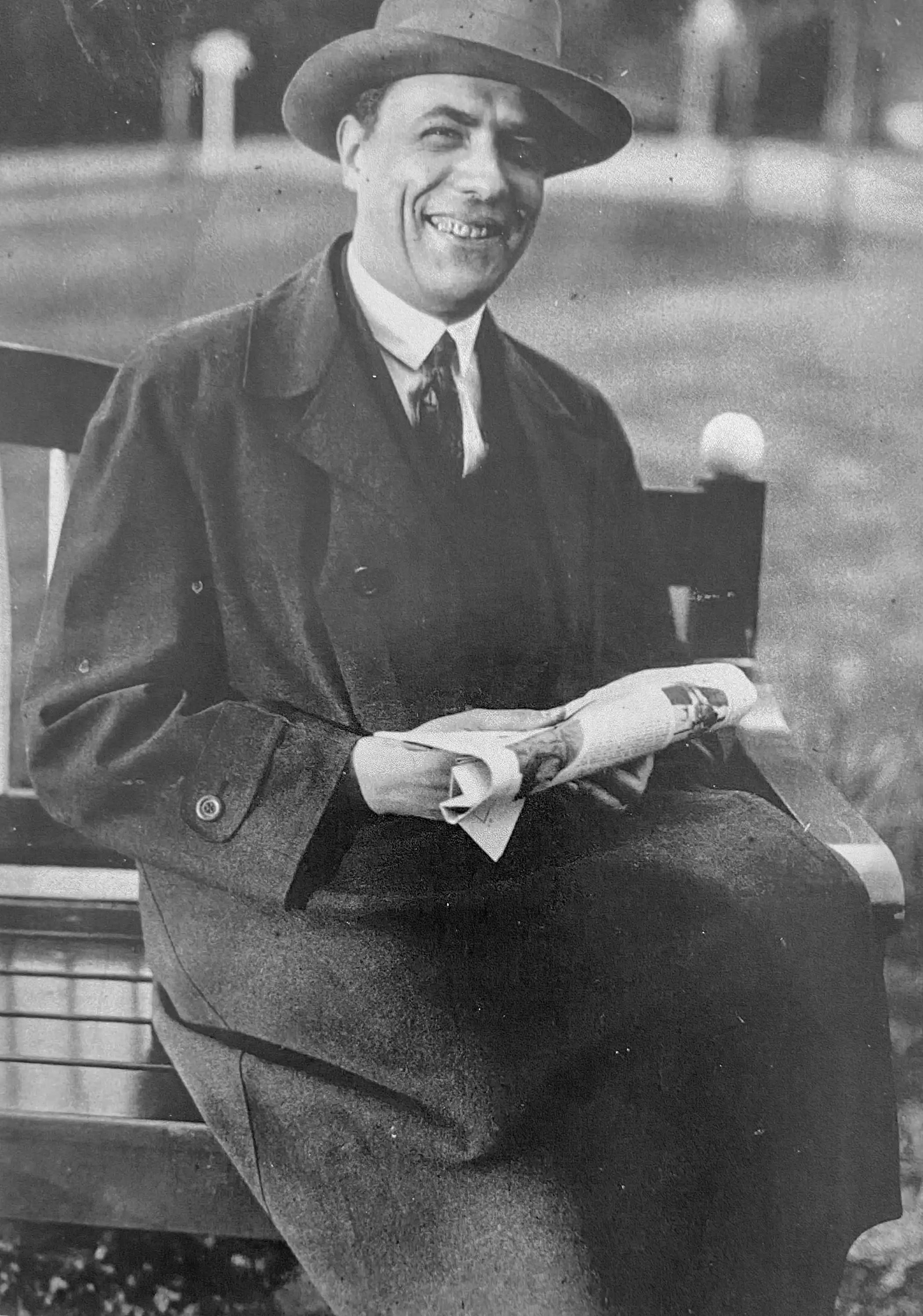

Bruno Taut and Carl Krayl

Krayl belonged to a group of architects who were of great importance for the widespread development of modernism in the Weimar Republic.

In the Arbeitsrat für Kunst (Workers Council for Art) and the Glass Chain, he contributed to the revolutionary and idealistic awakening of the post-war avant-garde in architecture. Through his contact with Bruno Taut, who had been appointed city planning officer in Magdeburg in 1921, Krayl was appointed head of the newly created design office in the building authority of the city of Magdeburg in May 1921.

After the First World War, the SPD won a majority in the city council for the first time with its mayoral candidate Hermann Beims. Beims had set himself the goal of giving Magdeburg more prestige and influence as a progressive and modern city. In 1919, he was elected unopposed and remained in office without interruption until 1931.

Important departments of the city were filled with committed personalities: the school board went to school reformer Hans Löscher, and Bruno Taut was appointed city planning officer in 1921. At the beginning of the 1920s, no other German city had granted a leading position to a representative of modern architecture. Taut’s position as city planning officer was fixed for twelve years.

Portrait of Carl Krayl, 1927

Colorful Magdeburg

Taut made significant changes to the city’s landscape. To him, color was a cultural and educational tool, a necessary part of modern architecture, and an inexpensive design element during times of raw material shortages.

Carl Krayl was one of the key figures in implementing the concept of New Magdeburg and ushering in a new era. As a leading member of Taut’s team at the building authority and project manager of Taut’s initiative for colored house paint in Magdeburg, Krayl provided color consulting services to homeowners and designed numerous color concepts for house facades.

Johannes Göderitz and Konrad Rühl supported him in the city planning office. At the city council meeting in April 1922, Hermann Beims announced: “In all cities, I see the struggle between two generations of art. For us, there is no question that we must side with the new, even if we do not understand it or know how it will prove itself” (Frühlicht, vol. 4, summer 1922, pp. 220–221).

In the summer of 1921, the historic Magdeburg town hall was painted inside and out. By 1923, another 80 buildings, mainly in the old town, had followed suit. Additionally, colorful newspaper kiosks and the first newly built residential buildings with colored facades appeared. Colorful Magdeburg became the talk of the town, attracting many visitors and a large professional audience. Postcards presented the cityscape as a crowd puller.

All of the projects were listed in a guide titled Guide to Viewing the House Paintings in the City of Magdeburg, which was published by the building authority in 1922.

Postcard ‘Greetings from colorful Magdeburg’, 1922

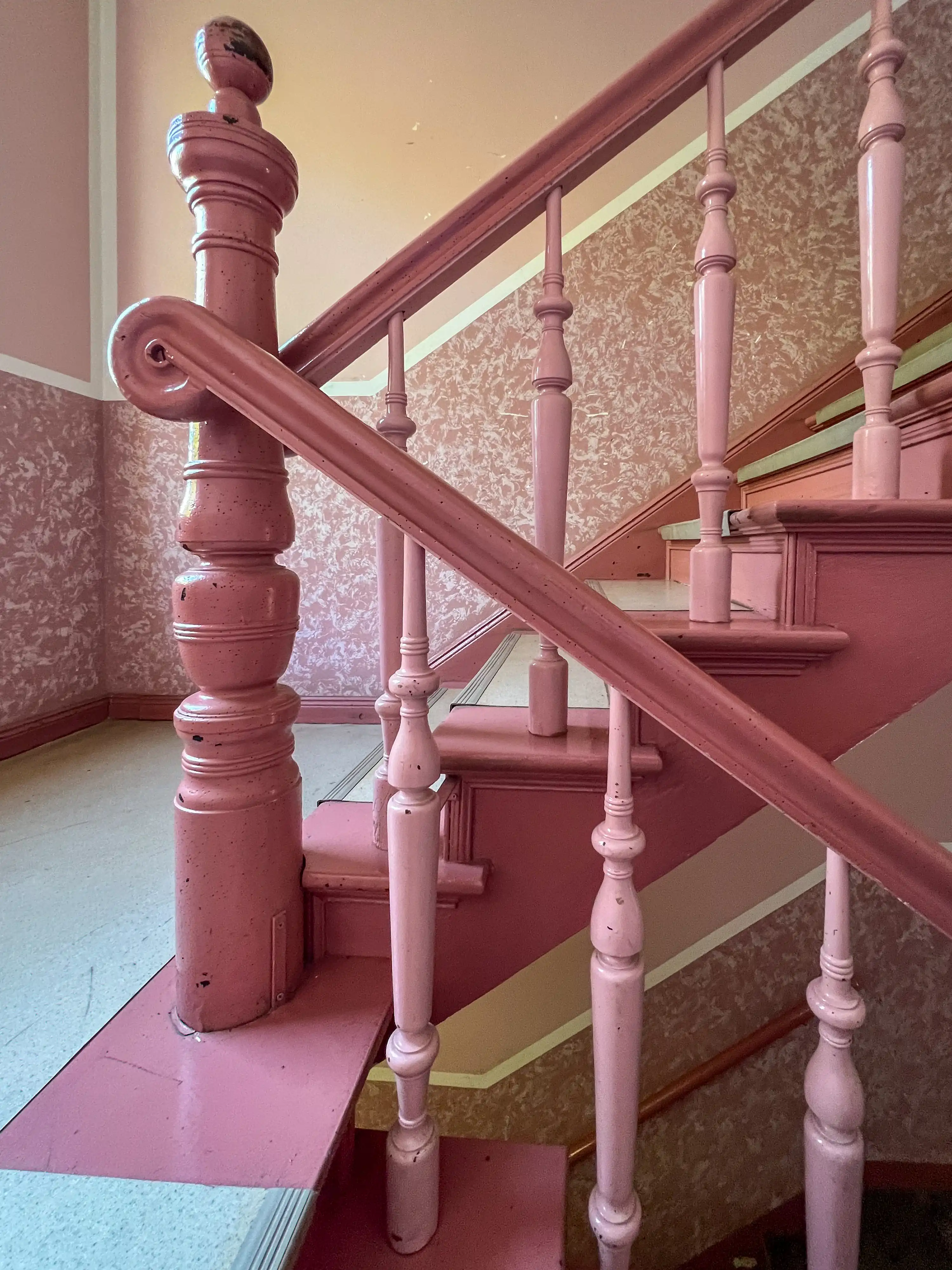

Otto-Richter-Straße

The twelve houses on the former Westerhüser Straße, now Otto-Richter-Straße, are particularly noteworthy. Krayl highlighted the existing window frames and stucco details in color. House number 2 was painted an ultramarine blue and featured a network of curved and jagged lines in yellow, green, red, and white.

During the turn-of-the-millennium renovation, the design was reconstructed based on a few color samples.

Facade painting on Otto-Richter-Straße in Magdeburg. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Facade painting on Otto-Richter-Straße in Magdeburg. Photo: Daniela Christmann

House painting on Otto-Richter-Straße in Magdeburg. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Facade painting on Otto-Richter-Straße in Magdeburg. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Facade painting on Otto-Richter-Straße in Magdeburg. Photo: Daniela Christmann

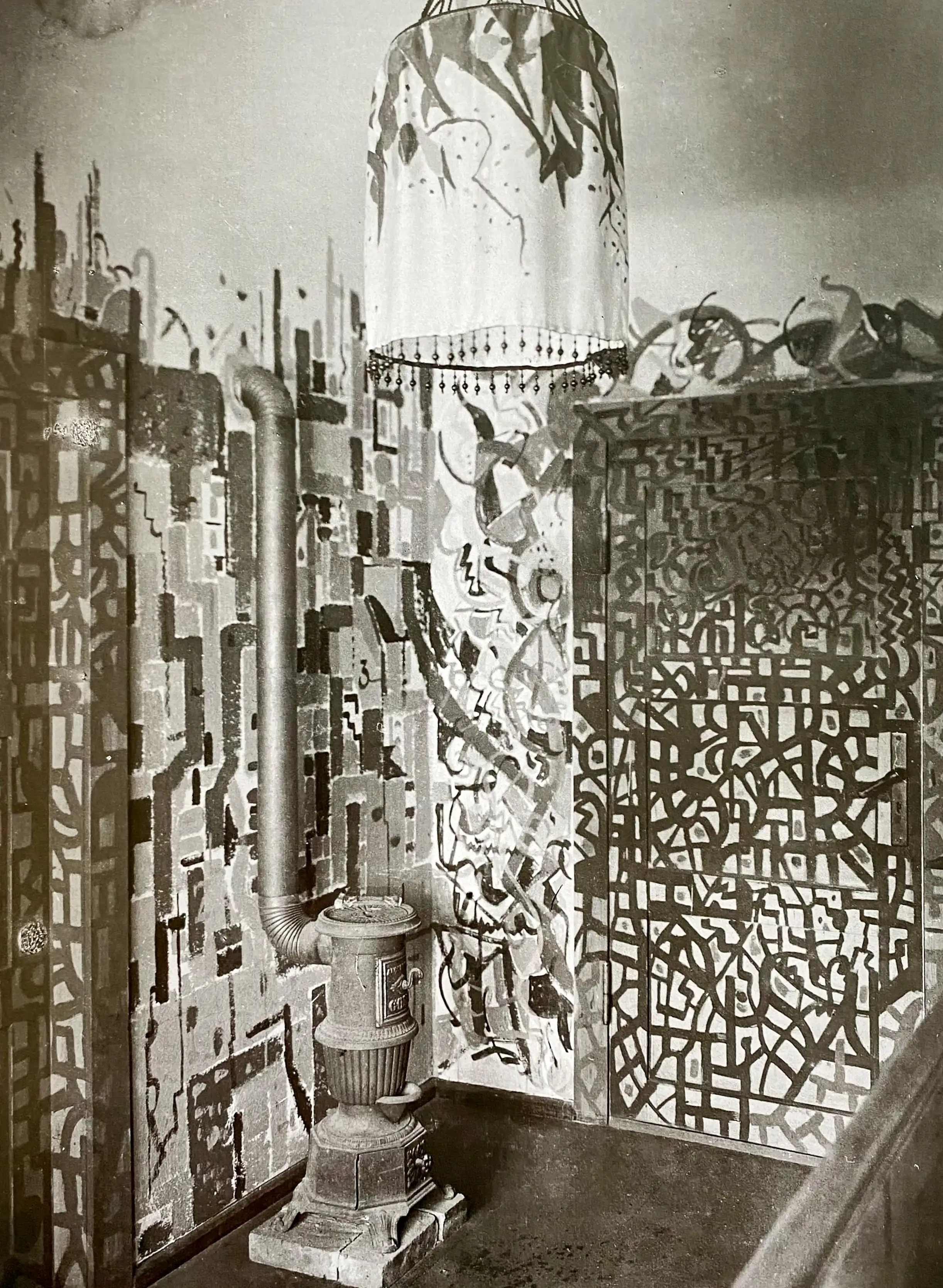

Carl Krayl House

In June 1921, he moved into a terraced house at 3 Bunter Weg in the newly built Reform garden city colony, designed by Bruno Taut. He made the house the subject of widespread interest by painting several interior rooms and pieces of furniture in vibrant colors.

Taut’s buildings for the Reform settlement were characterized from the outset by their colorful design. Krayl, a colleague of Taut’s at the building authority, was consulted on the color scheme for the houses.

Krayl also painted the interior of his own house. He continued the painting to the outside on the ground floor window at the front, creating a colorful frame for the façade opening.

The paintings on the walls and furniture clearly reflect the ideas and imagery of the Glass Chain, which was still prevalent in the summer of 1921.

Around 1927, Krayl changed the living room design, adopting the New Objectivity aesthetic of the time by painting the walls a single color.

Row house complex at Bunter Weg 3, Garden City Colony Reform, 1921. Architect: Bruno Taut. Carl Krayl’s residence with painted window frames, 1921/22

Row house complex at Bunter Weg 3, Gartenstadt Kolonie Reform, 1921. Architect: Bruno Taut. Residence of Carl Krayl. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Row house complex at Bunter Weg 3, Gartenstadt Kolonie Reform, 1921. Architect: Bruno Taut. Carl Krayl’s house with painted window frames. Photo: Daniela Christmann

House Krayl. Wall and door painting. Photo 1921/22

House Krayl. Wall and door painting. Photo 1921/22

Standard Clock on Staatsbürgerplatz

Krayl covered the public clock on today’s Universitätsplatz, which was built in 1908, with a network of colored areas. This adaptation was made to match the modern newspaper kiosk that stands next to it.

Standard clock at Staatsbürgerplatz with kiosk, 1921

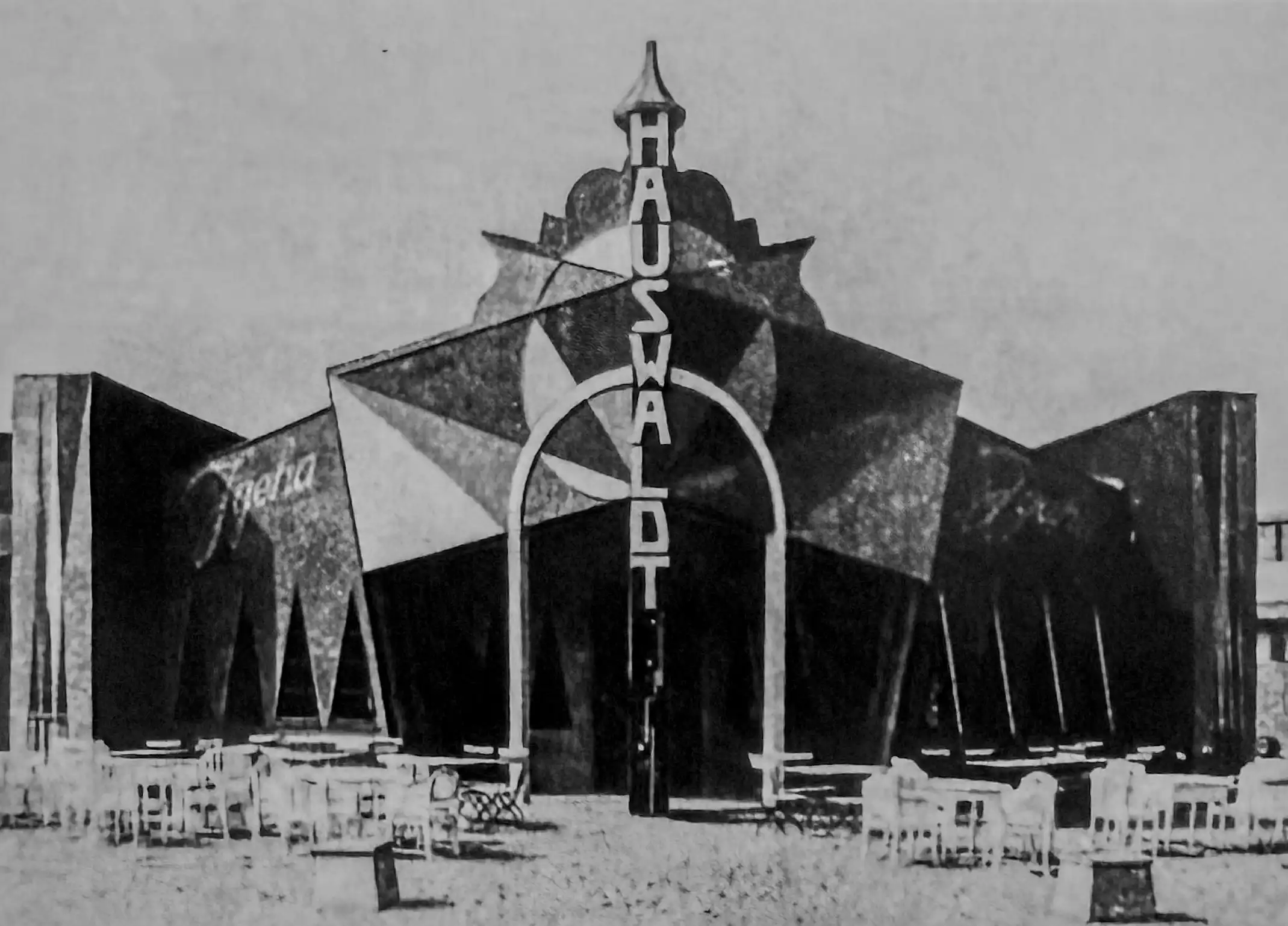

Hauswaldt Pavilion

In July 1922, Krayl began his first private project when he designed a pavilion for the chocolate manufacturer Johann Gottlieb Hauswaldt for the MIAMA exhibition (the Central German Exhibition for Settlement, Social Welfare, and Labor) in Magdeburg. Maximilian Worm supervised the construction of the pavilion, which led to a long-term collaboration.

Designed as a cocoa bar, the pavilion was located in a prominent position directly at the entrance to Lake Adolf-Mittag in Rotehornpark. Krayl designed a central building with an unusual shape and a multicolored exterior and interior that captivated onlookers.

After the exhibition ended, the city of Magdeburg leased the pavilion, which was not demolished until 1924.

The Magdeburg exhibition also led to Krayl’s direct contact with Rotterdam’s architect and city planner, J. J. P. Oud. He was Krayl’s guest on several overnight visits until 1923.

Beginning in March 1923, Krayl was granted unpaid leave from the building authority to collaborate with Maximilian Worm and Franz Hoffmann on the private construction projects “Central-Genossenschaft” and “Hotel Weißer Bär.”

Hauswaldt Pavilion, 1922. Architect: Carl Krayl. Photo 1922

Hauswaldt Pavilion, 1922. Architect: Carl Krayl. Photo 1922

New Objectivity

From 1923 onward, Krayl’s work underwent a transformative shift towards the New Objectivity style.

In February 1924, his resignation from the Building Authority took effect, after which he opened a joint office in Magdeburg with architect Maximilian Worm. He worked as a freelance architect in Magdeburg until November 1937.

He and Worm designed commercial buildings in Magdeburg, including the Landeskreditbank (1924) and the Allgemeine Ortskrankenkasse (1926), as well as the Schneidersgarten residential complex in Magdeburg’s Sudenburg district (1926).

New Building Movement

In 1926, Krayl joined the Der Ring architects’ association. Young architects came together in this association to promote the New Building movement.

Krayl incorporated the ideas of New Building into his housing estate projects in Magdeburg, for which he was solely responsible from 1927 onward. In June 1927, Krayl ended his collaboration with Maximilian Worm due to irreconcilable differences.

Housing Estates

After the Fermersleben, Cracau, and Curie (also known as Bancksche) housing estates were built starting in 1929, Krayl’s influence spread. These projects earned Magdeburg the title of “City of New Building.”

Krayl’s final projects in Magdeburg included expanding the Reform settlement, which was completed between 1932 and 1933; the trade union building; and the OLi-Lichtspiele cinema.

1933

After 1933, Krayl was classified as a “cultural Bolshevik” by the National Socialists and was no longer awarded public construction contracts.

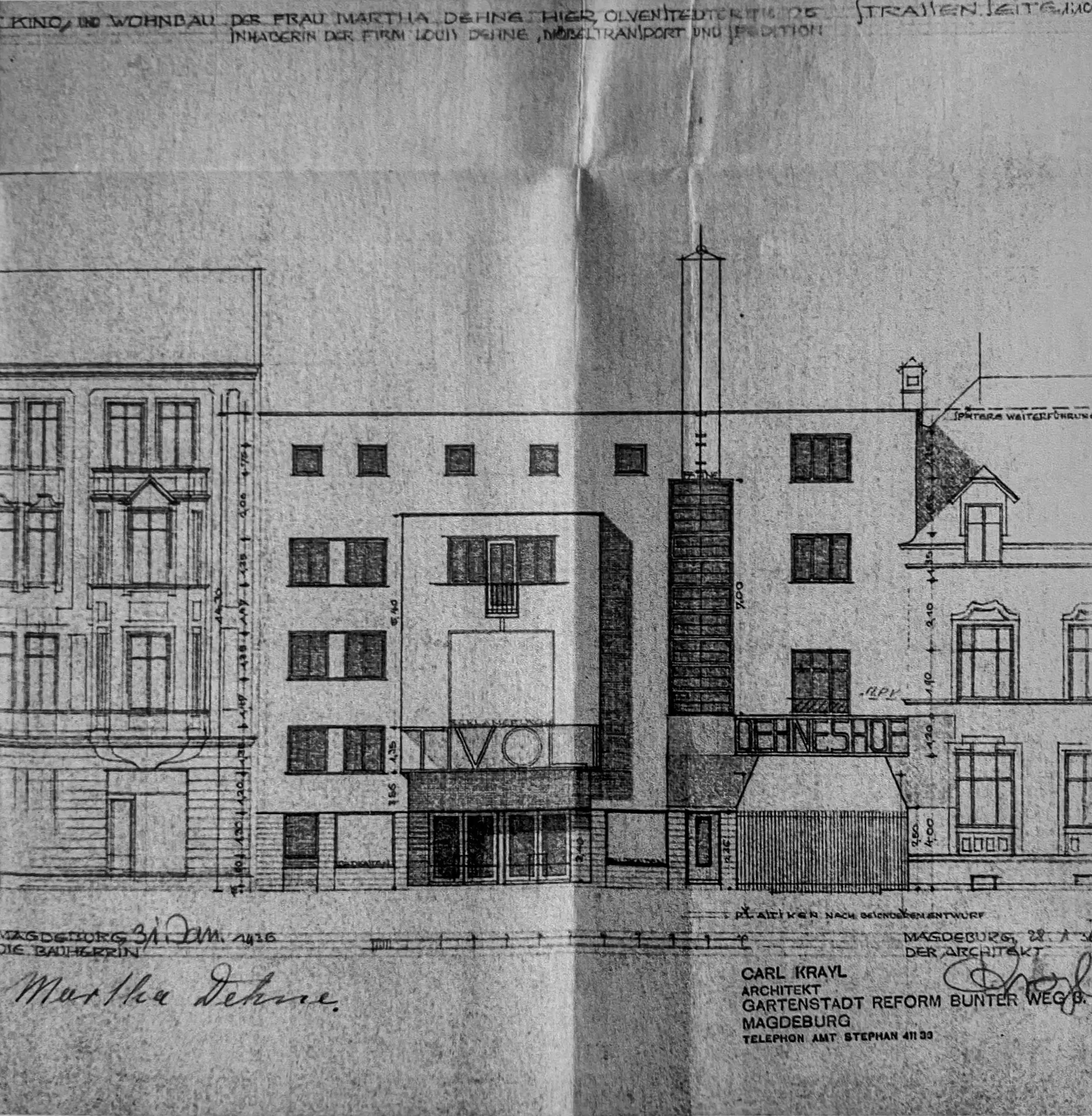

OLi Cinema

The Olvenstedter Lichtspiele cinema was built in 1936 for the freight forwarder Martha Dehne. Dehne commissioned Krayl to design and build a residential building and a cinema on the premises of her company, Möbeltransport und Spedition Louis Dehne.

OLi Cinema. Design: Carl Krayl, June 1936

OLi Cinema, 1936. Architect: Carl Krayl. Photo 1937

OLi Cinema, 1936. Architect: Carl Krayl. Photo taken after reconstruction in 1952

OLi Cinema, 1936. Architect: Carl Krayl. Photo 2003

OLi Cinema, 1936. Architect: Carl Krayl. Photo: Daniela Christmann

OLi Cinema, 1936. Architect: Carl Krayl. Photo: Daniela Christmann

The OLi cinema’s original modern design, featuring a flat pent roof and cubic bay window, received a building permit in 1936. However, the final design differed significantly from the original.

In 1937, Krayl was forced to give up his freelance work and became an architect employed by the Deutsche Reichsbahnbaudirektion Berlin (German Reich Railway Construction Authority in Berlin).

After the war ended, Krayl worked for Hans Scharoun for a while. As the city planning officer for the postwar Berlin magistrate, Scharoun was responsible for drafting the collective plan for Berlin’s reconstruction.

Residential building at Otto-Richter-Straße 2, 1922. Colour design: Carl Krayl

Residential building at Otto-Richter-Straße 2, 1922. Colour design: Carl Krayl