1919 (Design), 1922 – 1923 (Construction)

Design: Max Taut

Bahnhofstraße 2, Stahnsdorf, Brandenburg, Germany

The 156-hectare Stahnsdorf Forest Cemetery, located between Babelsberg and Stahnsdorf in southwest Berlin, was created around 1909 based on plans by landscape architect Louis Meyer.

The listed tomb of merchant and art patron Julius Wissinger’s family, designed by Max Taut in 1919, is located here.

Erbbegräbnis Wissinger, 1922-1923. Design: Max Taut. Photo: Daniela Christmann

The Wissinger Family

The Wissinger family originated from Spremberg in Saxony. In 1877, brothers Hermann Otto Julius Wissinger (1848–1920) and Paul Wissinger (1851–1919) founded J. & P. Wissinger, a seed trading company located at Landsberger Straße 46/47 in Berlin.

After the turn of the century, the brothers decided to build a new, five-story warehouse on a 5,000-square-meter plot of land. The South-East Warehouse, designed by architect Kurt Berndt, was built between 1906 and 1907 at Pfuelstraße 6a/7 in Berlin-Kreuzberg.

Julius Wissinger (1884–1967), Hermann Otto Julius’s son, and his wife, Helene Wissinger (née Schupp, 1892–1976), funded the construction of the tomb.

Between 1923 and 1932, Helene and Julius became patrons of artists and musicians. In 1922, the couple commissioned architects Fritz Schupp and Martin Kremmer to design a family home in the Karolinenhof villa colony in southeastern Berlin.

The friends who spent summer weekends at the villa included graphic designer Herbert Bayer, architect Marcel Breuer, painters Richard Ziegler, Bruno Krauskopf, and Robert Genin, as well as pianists Julius Goldstein, Alexander Rödiger, and Henny Bromberger. Psychoanalyst Edgar Michaelis and art historian Klara Steinweg were also among their number.

A small weekend house in the garden allowed members of the group to live and work there for extended periods. Meanwhile, the Wissingers owned a studio near Pariser Platz that they made available to friends.

Not only were Helene and Julius Wissinger generous hosts, they also provided financial support to various artists, including Otto Freundlich and Robert Genin. The Wissingers purchased paintings and commissioned Freundlich to design a stained glass window for Julius Wissinger’s study.

After the stock market crash of 1929, however, the family’s financial situation deteriorated significantly. In 1932, they gave up the Karolinenhof house and moved back to the city.

Wissinger Tomb

Following the deaths of Hermann Otto Julius Wissinger (1848–1920) and his granddaughter, Ingrid Wissinger (1920), on April 7, 1920, the Wissinger family purchased a 50-square-meter plot within their family burial plot at the Southwest Cemetery in Stahnsdorf.

They commissioned architect Max Taut to design the family tomb. It is unclear how he was chosen for the task. However, Helene and Julius Wissinger were probably familiar with Taut’s earlier designs and works, or at least knew of him through their circle of artist friends.

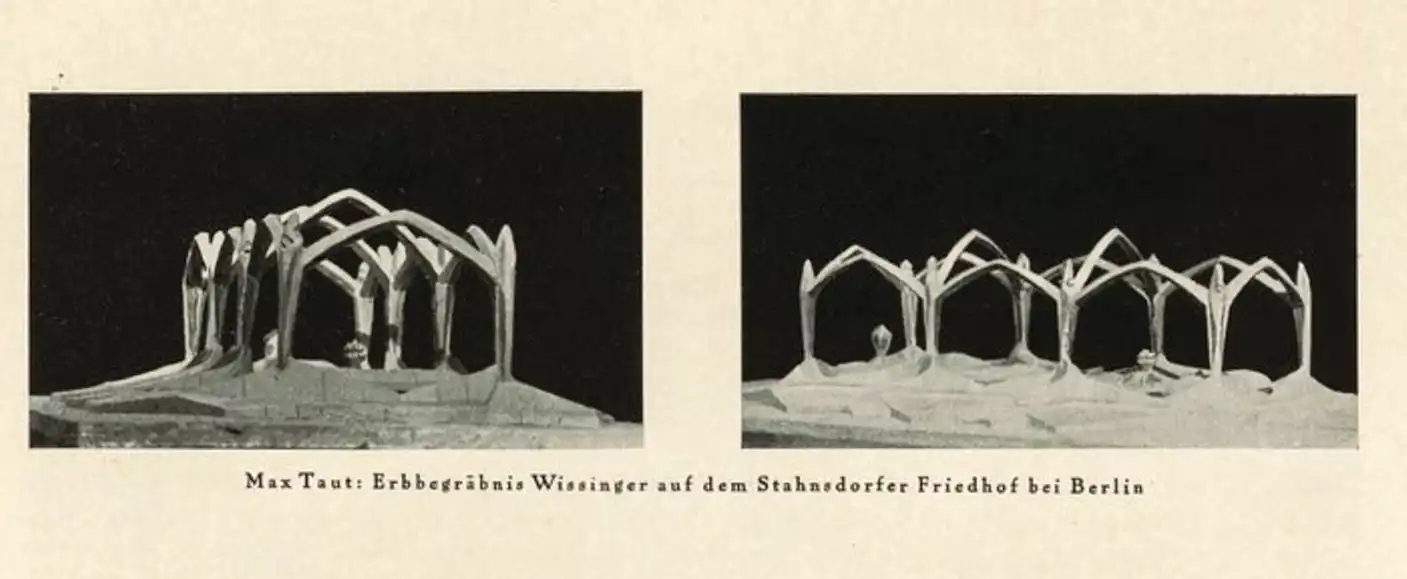

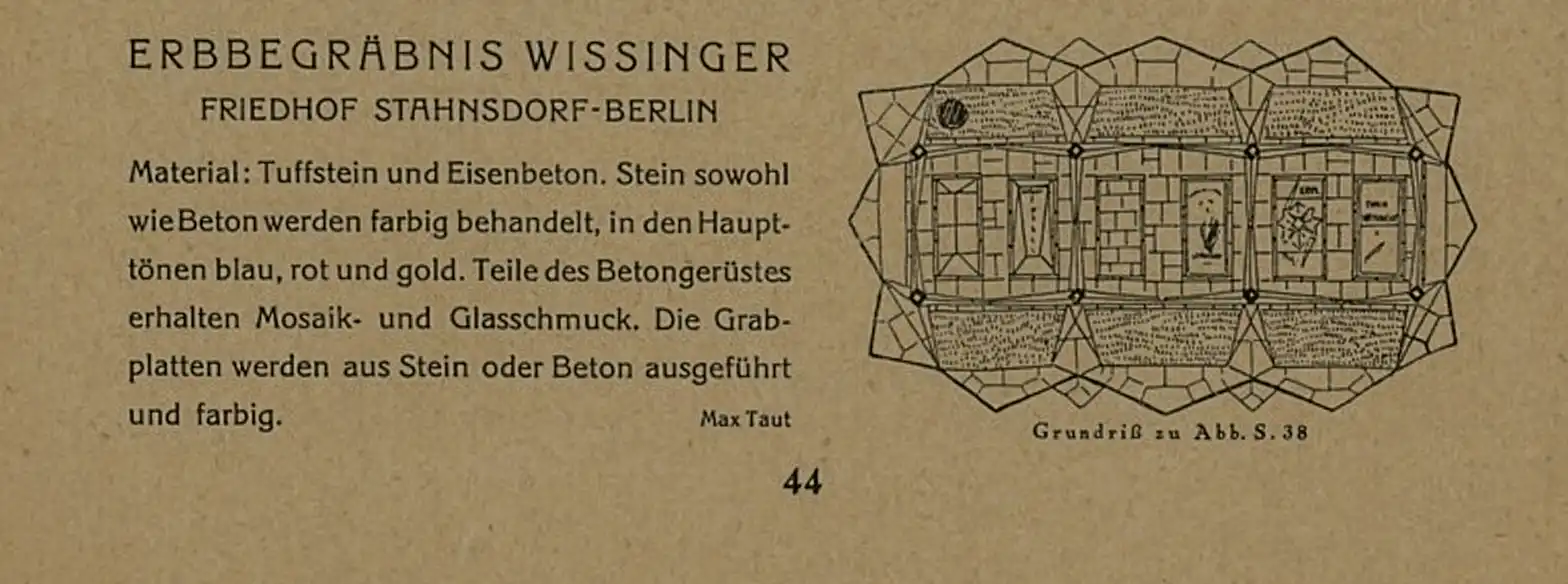

The tomb’s design was published in the second issue of the magazine Frühlicht (first year, Magdeburg, 1921), edited by Bruno Taut. It was built in a slightly modified form between fall 1922 and spring 1923.

Design Erbbegräbnis Wissinger. Frühlicht, 1921

Layout Erbbegräbnis Wissinger. Frühlicht, 1921

Max Taut, Blütenhaus (Flower House), 1921. Watercolor and pencil on cardboard. Estate of Max Taut, Archive of the Architecture Collection of the Academy of Arts, Berlin

The gravestone for Hermann Otto Julius Wissinger was designed by Otto Freundlich, a friend of Julius Wissinger’s.

The rectangular family grave is located in a clearing at one of the four corners of a crossroads. Two parallel rows of four concrete supports, connected lengthwise and crosswise by flat, pointed concrete arches, form a framework surrounding the grave area, which contains seven graves.

Erbbegräbnis Wissinger, 1922-1923. Design: Max Taut. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Erbbegräbnis Wissinger, 1922-1923. Design: Max Taut. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Erbbegräbnis Wissinger, 1922-1923. Design: Max Taut. Photo: Daniela Christmann

The cross-section of the downward-tapering supports is a square with overlapping corners that is cut several times on all four sides, forming sharp ridges and edges. The supports end in pointed roofs at the top, beneath which small concrete crabs are attached.

Erbbegräbnis Wissinger, 1922-1923. Design: Max Taut. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Erbbegräbnis Wissinger, 1922-1923. Design: Max Taut. Photo: Daniela Christmann

The pointed arches extending from the sides of the supports are irregular quadrangles with overlapping cross-sections that become smaller towards the top. The two middle arches are raised above the others.

The entire substructure is made of tuff stone. Tetrahedral thresholds that rise toward the supports surround the recessed space within the concrete structure, which is lined with slabs.

On the two narrow sides and between the two middle supports of the long sides, the lowest point of the thresholds is located directly beneath the tops of the arches. For the remaining thresholds on the long sides, this point is closer to the corner supports.

Pointed, crystalline concrete forms are attached to the bases of the supports; some face the interior, while others engage with the thresholds and other tetrahedral tuff stones. These stones become flatter toward the outside of the supports. Together with the thresholds on the long sides, they delimit three trapezoidal plant beds on each long side and one on each short side.

Erbbegräbnis Wissinger, 1922-1923. Design: Max Taut. Photo: Daniela Christmann

A jagged border of tuff stone slabs surrounds the entire grave, separating the plant beds from the outside. The border’s slabs protrude a few centimeters from the ground and slope outward slightly.

The structure sits atop a brick crypt filled with soil. Concrete beams placed at regular intervals above the crypt support the grave slabs.

The westernmost grave is unoccupied and marked only by a rectangular concrete frame. To its left is the grave of Ingrid Wissinger. Two concrete beams lie close together on a rectangular concrete frame. On top of these beams is another short concrete beam on which a square column stands in the center. On top of the column is a cube whose corners have been beveled to form small triangular surfaces. The child’s name and birth and death dates are carved into three sides of the column.

Hermann Otto Julius Wissinger was buried to the left of this grave. Originally, a sculpture by Otto Freundlich adorned the concrete gravestone. The names and dates of the deceased were carved into the front of the gravestone. Today, the grave is covered by a three-part limestone slab. The names and dates are engraved on the middle section of the slab. As with Ingrid Wissinger, an eight-pointed star symbolizes the date of birth here, too.

Erbbegräbnis Wissinger, 1922-1923. Design: Max Taut. Photo: Daniela Christmann

The fourth grave belongs to Amalie Wissinger (née Schunack; 1856–1942). Her gravestone is identical in design and material to that of her husband, Hermann Otto Julius Wissinger.

The next two graves are only marked by rectangular concrete frames. During restoration work, a coffin was found in the left grave. Charlotte Wissinger, a daughter of Helene and Julius Wissinger who died in 1946, may have been buried here without a gravestone.

The easternmost grave is that of Alfred Wissinger (1889–1940). Its three-part grave slab is identical in design and material to Hermann Otto Julius Wissinger’s.

The Glass Chain

Max Taut’s design can be traced directly back to drawings in correspondence between members of the Glass Chain architects’ association.

The Glass Chain was an artists’ community founded by Bruno Taut, consisting mainly of architects. The medium for mutual exchange was circular letters in the form of correspondence.

The Glass Chain

Max Taut’s design can be traced directly back to the drawings in the correspondence of the Glass Chain architects’ association members.

Founded by Bruno Taut, the Glass Chain was an artists’ community consisting mainly of architects. The medium for mutual exchange was circular letters in the form of correspondence.

These letters, signed with pseudonyms, were written from November 1919 to December 1920. The group included Bruno Taut (pseudonym “Glas”), Max Taut (no pseudonym), Wilhelm Brückmann (“Brexbach”), Alfred Brust (“Cor”), Hermann Finsterlin (“Prometh”), Paul Goesch (“Tancred”), Jakobus Goettel (“Stellarius”), Otto Gröne, Walter Gropius (“Maß”), Wenzel Hablik (initials “W. H.”), Hans Hansen (“Antischmitz”), Carl Krayl (“Anfang”), Hans Luckhardt (“Angkor”), Wassili Luckhardt (“Zacken”), and Hans Scharoun (“Hannes”).

Two sketches by Max Taut, which appear to refer to the Wissinger tomb, were published in the Frühlicht series: “Marmordom” (1919) and “Blütenhaus” (1921). According to Frühlicht, issue 2 (Magdeburg, 1921), the tomb was to be constructed of tuff stone and reinforced concrete in the main colors of blue, red, and gold, and decorated with mosaics and glass inlays.

Erbbegräbnis Wissinger, 1922-1923. Design: Max Taut. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Erbbegräbnis Wissinger, 1922-1923. Design: Max Taut. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Color Scheme

However, the absence of color is the decisive change that alters the overall appearance of the tomb compared to the original design. In Frühlicht, Max Taut provided the following description: “Material: tuff stone and reinforced concrete. Both the stone and the concrete will be colored, mainly in shades of blue, red, and gold. Parts of the concrete framework will be decorated with mosaics and glass. The gravestones will be made of stone or concrete and colored.”

However, a color analysis carried out prior to the restoration revealed that neither the mosaics nor the glass decorations had been implemented, and the color treatment had not been carried out.

Contemporary Reactions

The tomb, which was unusual then as it is today, caused a stir and protests after its completion. Initially, the Protestant Church Synod’s objections (the exact content of which is unknown) resulted in Otto Freundlich’s tomb slab being buried in the ground.

However, the removal of the sculpture did not stop the protests. About a year later, in July or August of 1924, newspaper articles reported that the Protestant synod passed a motion to remove the entire tomb. The details of how the dispute unfolded and how the demolition was prevented are unknown.

In December 1925, the Wissinger family purchased an additional 77 square meters of land in the cemetery. The exact location is unknown. It is possible that this purchase was related to the controversy surrounding the tomb, and that the family felt compelled to acquire land around the structure as a “buffer zone” from other graves.

Conclusion

The Wissinger tomb, designed by architect Max Taut, was built between 1922 and 1923 as an expressionist spatial structure made of concrete above the actual burial site.

An arcade of shafts and pointed arches emerges from stylized, crystalline rootwork, conveying the spatial idea of a three-bay Gothic hall.

The building’s striking effect is created by its purely imaginary space and pure construction, which serve no purpose other than themselves and their form. This creates a sacred space with the modern material of reinforced concrete. The frame construction realizes the romanticized formal canon of Gothic architecture of the utopian avant-garde.

Substantial restoration work was carried out on the Wissinger family tomb in 1987 and 1988. This work is documented in the publication Frühlicht in Beton by Christoph Fischer and Volker Welter, published in Berlin in 1989.

Extensive crack repair and surface treatment was carried out in 2004 and 2012.