Schocken Department Store, 1927-1930. Architect: Erich Mendelsohn. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Schocken Department Store, 1927-1930. Architect: Erich Mendelsohn. Photo: Daniela Christmann

1928 – 1930

Architect: Erich Mendelsohn

Stefan-Heym-Platz 1, Chemnitz, Germany

Erich Mendelsohn, who had already designed department stores for the Simon and Salman Schocken brothers in Nuremberg and Stuttgart, was commissioned in 1927 to plan the Chemnitz branch of the Zwickau-based group.

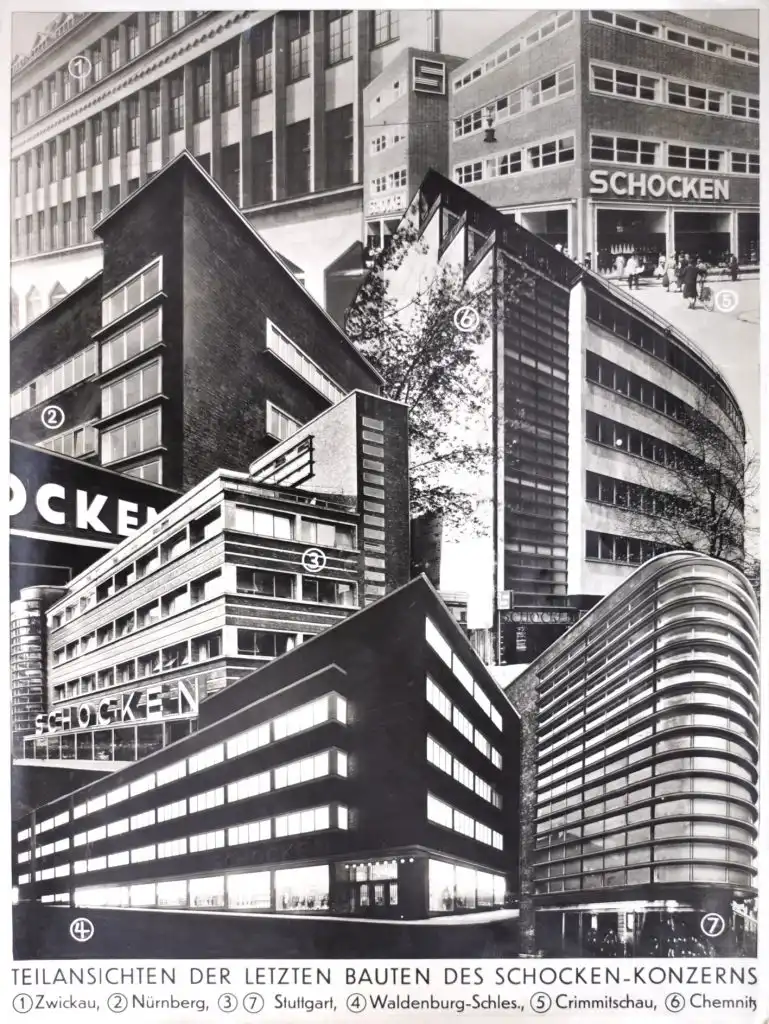

Schocken Department Stores. Contemporary collage

Schocken Department Store Nuremberg, 1925-1926. Architect: Erich Mendelsohn. Contemporary picture postcard

It was to be the largest Schocken department store in Germany. Construction began in 1929, and the department store opened on May 15, 1930.

The department store is a listed building and one of the icons of Modernist architecture.

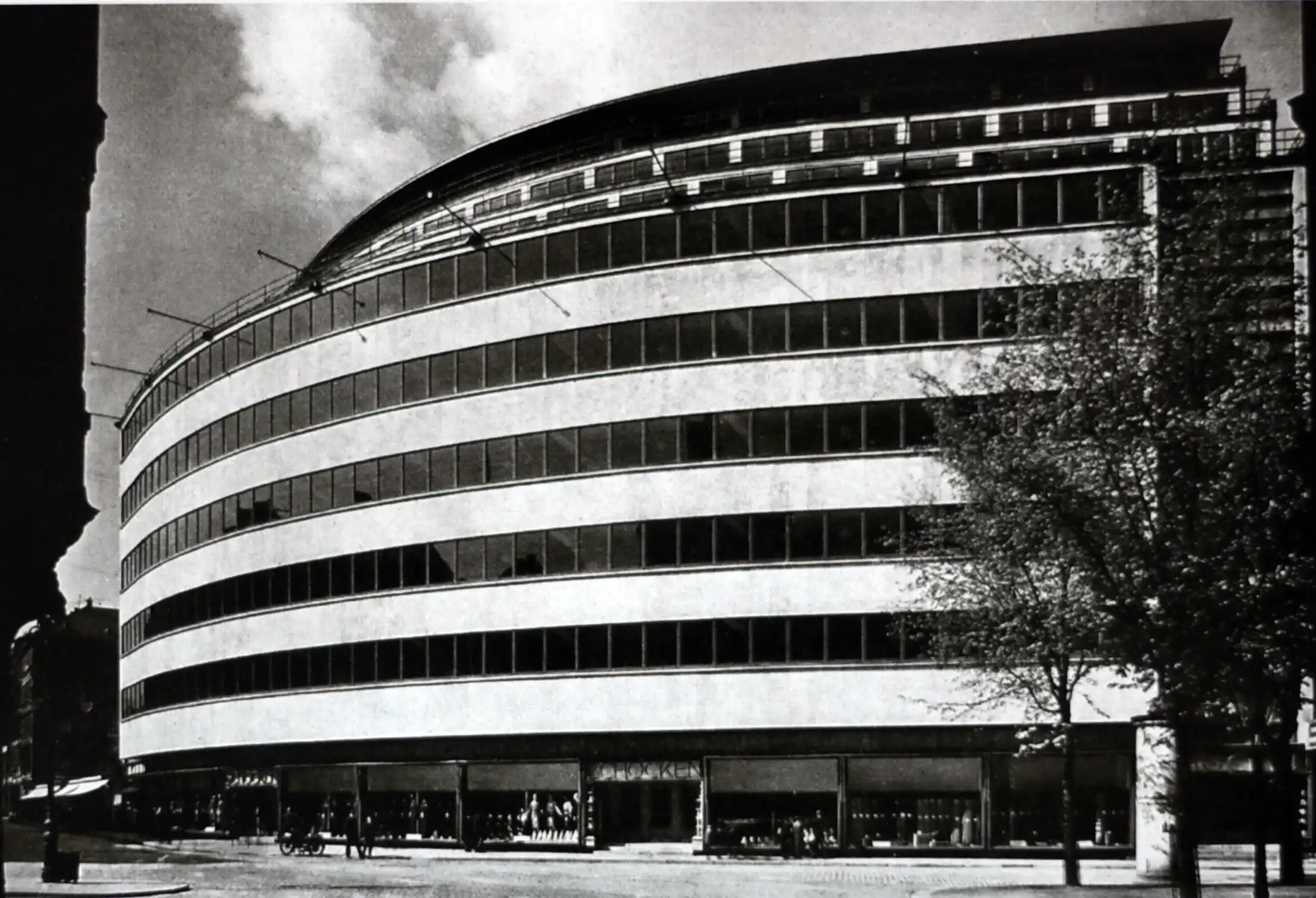

Schocken Department Store, 1927-1930. Architect: Erich Mendelsohn. Contemporary photograph. Source: Salman Schocken Family Archive

Chemnitz

The great success of his Nuremberg department store led to another commission from the Schocken Group for Mendelsohn, even before the Stuttgart building was completed. This time, he was tasked with planning the large Schocken department store in the flourishing industrial city of Chemnitz.

Even in 1930, when the consequences of the global economic crisis were already becoming apparent, the positive assessment of the opportunities in Chemnitz was well founded.

The same applied to Nuremberg and Stuttgart, which had similar conditions, especially in terms of economic sectors, degree of industrialization, and resulting purchasing power of the population.

Industrial Town

Chemnitz was the center of an industrial area stretching from the edge of the Ore Mountains to the Central Saxon Highlands. It was one of the most important industrial cities in Saxony and the central German region.

Its main products were hosiery, knitwear, textiles, textile machinery, machine tools, office machinery, chemicals, and motor vehicles, including accessories, and furniture.

Throughout the 19th century, the town developed into a rapidly growing industrial metropolis. Its location and proximity to the Lugau-Oelsnitz-Zwickau coalfield and the densely populated Central Ore Mountains favored its development.

In addition to Chemnitz’s 348,000 inhabitants and their purchasing power, the new department store could also count on the purchasing power of the numerous commuters who came to the city every day.

Planning and Execution

Erich Mendelsohn gave the department store an unmistakable appearance with just a few sketches that attracted the attention of all passersby. There are only five drawings in his estate.

Notes in letters to his wife, Luise Mendelsohn, indicate that the planning process began in December 1927 but continued until spring 1929, when the building application could finally be submitted.

Despite the need for further changes, construction began in the summer of 1929. Unlike with the two earlier Schocken buildings in Nuremberg and Stuttgart, the company entrusted the supervision of the work to its in-house construction manager, Heinze, much to Mendelsohn’s displeasure.

In February 1930, the city of Chemnitz approved the modified plans. By this time, the house was almost complete.

The grand opening took place on May 15, 1930, in the presence of Salman Schocken and Erich Mendelsohn.

Plot and Urban Location

The quarter-circle-shaped property on the edge of Chemnitz’s city center had its front side facing the circular section. The side façades were irrelevant in terms of urban space, and the design was characterized by considerations of use.

Therefore, Mendelsohn’s task was quite different from that of the department store, which could be seen from all sides and was under construction in the middle of Stuttgart’s old town.

In Chemnitz, the effect had to come from a single view. The goal was to express the department store’s character as a warehouse and to create a clear separation between the sales floors and the stairwells from the outside.

Schocken Department Store, 1927-1930. Architect: Erich Mendelsohn. Contemporary photograph. Source: Salman Schocken Family Archive

Construction

The Schocken department store in Chemnitz is a nine-story reinforced concrete building. Due to the curved shape of the façade, the columns are spaced at different distances.

The outermost row of columns is 2.5 meters behind the first-floor façade and 3.5 meters behind the first-to-fourth-floor façade to accommodate the projecting bay window.

The main façade is a curtain wall.

Mendelsohn interspersed four staircases and three elevators at the outermost points of the circular segment to break up the sales areas, which are only separated by the supporting structure. There were also four escalators, a freight elevator, and a lifting platform.

However, unlike older department stores, he dispensed with an atrium in favor of larger sales areas.

Schocken Department Store, 1927-1930. Architect: Erich Mendelsohn. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Schocken Department Store, 1927-1930. Architect: Erich Mendelsohn. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Schocken Department Store, 1927-1930. Architect: Erich Mendelsohn. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Façade and Windows

Mendelsohn focused primarily on designing the main façade. He developed window formats that connected the different parts of the façade. Two contrasting forms stand out: the horizontal character of the sales floors and the vertical lines of the two side stairwells. The horizontal window formats of the stairwells ran between the shop windows and the projecting bay window across the entire width of the façade. This emphasized the floating appearance of the 56-meter-wide, non-load-bearing façade.

Schocken Lettering

Mendelsohn originally planned to install huge letters spelling out “SCHOCKEN” on the roof of the building. However, he decided against it once the building was completed. Instead, he installed small letters above the department store’s four entrances.

The lettering had become superfluous as an advertising medium. The building itself, its architecture, became Shocken’s new signet. The staging of the architecture through artificial lighting was crucial to this effect. It created the positive-negative effect that Mendelsohn had already achieved with the Stuttgart building.

Schocken Department Store, 1927-1930. Architect: Erich Mendelsohn. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Schocken Department Store, 1927-1930. Architect: Erich Mendelsohn. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Interior Design

In keeping with the credo of Schocken and Mendelsohn that the primary feature of a store is the merchandise, the interior was simply furnished. The windows were 1.45 m high from the floor to accommodate shelves on the outer walls.

The windows extended to the ceiling, directing light upward and onto the merchandise and sales area. The highly rational building deliberately dispensed with all ornamentation.

Building Description and House Sign

When the project was finished, Schocken KG published Erich Mendelsohn’s description of the building, along with numerous illustrations and plans, in several trade journals. The company also printed the text as an advertisement in the Chemnitz daily press. The article was supplemented by a list of all the companies involved in the construction.

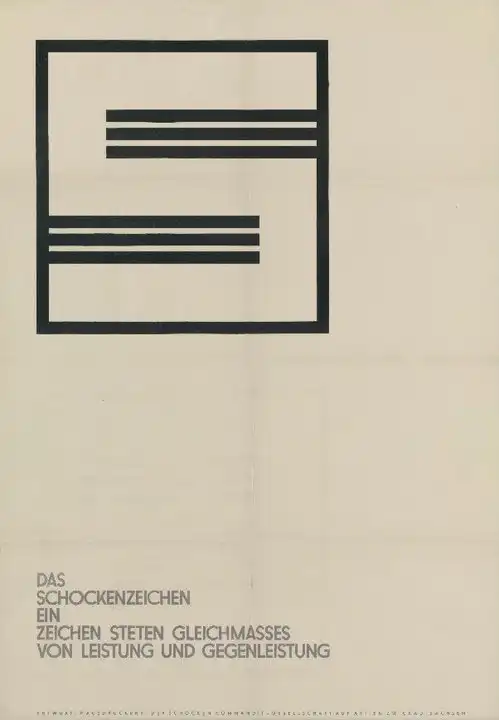

Each advertisement featured the company’s logo from the outset: a stylized “S” designed by Mendelsohn.

The following excerpts from Mendelsohn’s building description provide an overview of the building’s architecture and construction.

Schocken House Sign. Design: Erich Mendelsohn

Location (Mendelsohn Building Description)

‘The building site is located on the former utility building plot at Brückenstraße 9 and 11. It forms a circular section that opens up towards Brückenstraße, rounding off the protruding corner. This creates an architecturally effective, unbroken facade and improves the flow of street traffic.

The building plot is bordered by Brückenstraße on the periphery and by Brückenschule and the neighboring Schnicke on the sides. The courtyard can be accessed via a passageway from the street.

The entire building tract has six full stories, each with a height of five or three meters, as well as a continuous basement and a courtyard with a cellar. This results in a main cornice height of approximately 23.5 meters. There are also two additional set-back storeys at a 45-degree angle and a covered terrace above the top storey.

The main wing of the school is built to its full height. On the other side, the high-rise building extends 21 m from the street.

An approximately 56-meter-wide and 1-meter-projecting oriel protrudes from the middle of the front above the first floor. It is supported by cantilevers of the reinforced concrete skeleton.

The oriel is flanked on both sides by vertical staircases with glass surfaces that accommodate the ribbon of windows between the bay and the shop window. Four entrances are evenly distributed across the entire front.

Construction and Materials (Mendelsohn Building Description)

“The building has a reinforced concrete skeleton and is filled with brickwork. It is plastered on the courtyard and side fronts. The street front is clad in Auer limestone. The column construction steps back 3.50 meters from the front of the bay window, creating an open storefront and shop window.

Four stairwells, three standard passenger elevators with micro-fine adjustment, four escalators from the first to the fifth floor, a freight elevator, and a lifting platform serve traffic. The stairwells have a flight width of 2.20 meters and run from the first to the eighth floor.

A fourth staircase with a flight width of 1.20 meters is provided for the sixth, seventh, and eighth floors, which are used as office and storage spaces. From the first to the fifth floor, it is not connected to the department store.”

Lighting (Mendelsohn Building Description)

“The windows on the courtyard and street fronts are 1.80 m above the floor, allowing for shelves on the outer walls. The windows extend directly below the ceiling, casting light onto the ceiling, which reflects it onto the goods and sales area. This system has been used in all modern department stores since the Schocken Building in Nuremberg. On the street side, continuous bands of windows are present because the cantilevered construction at the front of the windows requires no supports. This avoids any loss of light area. The courtyard fronts have single windows.”

Heating and Ventilation (Mendelsohn Building Description)

“In conjunction with an air heating system, a low-pressure steam heating system provides heat to the building. The entire mechanical heating system is housed in the basement.

Artificial ventilation is provided for the basement and the first through fourth floors.”

Design of the Rooms and Façade (Mendelsohn Building Description)

“All rooms are kept in light colors. In conjunction with the large ribbon windows, they lend the entire building the greatest possible brightness.

All floors are covered with linoleum and the staircases with Yara wood. The walls of the front staircases on the first floor and the main staircase on the courtyard side are clad in Solnhofer tiles from floor to ceiling. The toilets and ancillary rooms are tiled, and the floor of the food room is made of sintered tiles.”

General Information (Mendelssohn Building Description)

“The very rational building deliberately dispenses with anything decorative. Even the shop windows have plain wooden frames. Only the parapet areas on the street front are clad in a noble material. The façade’s impressive appearance stems from its height, the fine proportions of the staggered building mass, the clear structure of the light-colored front, the supported, column-free, and consequently floating oriel structure, the ascending, continuous staircase windows, and the panels of the recessed floors that complete the structure. Visible from afar, the façade dominates the adjoining complex of houses and symbolizes the importance of the Schocken House.”

Column-free Façade

In addition to the facts, Erich Mendelsohn’s description of the building contains references to his design intentions, particularly in the general information section. The column-free façade seemed particularly remarkable to him.

With the help of the cantilever construction, he designed the façade without interruptions. This means that the window and parapet bands extend in a sweeping arc from one staircase to the next, spanning almost 57 meters.

The base level, with its large-format shop windows and four entrances, as well as the two fully glazed stairwells, forms the frame for the dynamically stretched surface of the bay window.

Mendelsohn creates the illusion of an additional storey by arranging 25 narrow, rectangular windows in front of each stairwell. This reinforces the vertical elements on the sides of the main façade.

These windows’ dimensions continue in a narrow band above the large shop windows of the ground floor. The cantilevered bay begins above that. Set back one meter behind the level of the windows and parapets, these elements make the bay appear to float.

The upper stories step back even further. The seventh and eighth stories span a smaller radius between the straight outer edges of the building. Their cornices are set back at a shallow angle.

The offset from the main façade is 4.5 meters for the seventh floor and an additional 3.5 meters for the eighth. These two floors also lose space in the depth of the plot. The ninth floor and covered terrace are set back another 3.50 meters and barely form a structure.

A flat roof placed over the superstructures closes off the building at the top. Beneath it is a glazed wall slab with no function and supports.

Schocken Department Store, 1927-1930. Architect: Erich Mendelsohn. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Schocken Department Store, 1927-1930. Architect: Erich Mendelsohn. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Schocken Department Store, 1927-1930. Architect: Erich Mendelsohn. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Schocken Department Store, 1927-1930. Architect: Erich Mendelsohn. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Schocken Department Store

After opening on May 15, 1930, the building operated as a department store for over seventy years. It was first known as Kaufhaus Schocken from 1930 to 1938, then as a Merkur store from 1939 to 1945. After that, it was a HOWA and Centrum department store until 1990, when it became Kaufhof.

1939

Following the ‘Aryanization’ of 1938, the former Schocken department stores operated as Merkur-Aktiengesellschaft beginning in January 1939. The head office remained in Zwickau, and the department stores and some of the company’s production facilities continued operating. The stocking factory operated by Schocken in Chemnitz also continued to produce items for sale.

After 1945

Following Germany’s capitulation in May, the Chemnitz department store resumed operations.

On June 30, 1946, all Schocken branches in Saxony were expropriated as part of a referendum.

While the department stores in the western zones were returned to Schocken by 1949, the company was unable to regain its pre-war size. In 1953, Salman Schocken sold his shares to the Horten department store group.

The Schocken Department Store in Chemnitz had only suffered minor damage during the war. This allowed at least the first floor of the building to be used for retail again.

In 1947, Volkssolidarität Chemnitz established an exchange center on the second floor of the department store to address the shortage of goods caused by the war.

Another name change occurred in 1948 when the Trade Organization took over the building. The former Schocken and Tietz stores became HO department stores, which later both bore the name CENTRUM.

From 1990 to 2001, a branch of Kaufhof was housed in the former Schocken department store.

Refurbishment and conversion

Following an extensive renovation from 2010 to 2014, the building became home to the Chemnitz State Museum of Archaeology. The façade has been restored in keeping with its listed status, and recessed walls have been used to bring the floor plan to life.

Three openings in the ceiling connect the floors of the permanent archaeological exhibition.

In addition to the permanent exhibition, other areas showcase the life and work of architect Erich Mendelsohn, the Schocken department store group, and entrepreneur Salman Schocken.

Kaufhaus Schocken, 1927-1930. Architekt: Erich Mendelsohn. Foto: Daniela Christmann

Kaufhaus Schocken, 1927-1930. Architekt: Erich Mendelsohn. Foto: Daniela Christmann

Hoi Daniela

Zuerst einmal einen ganz herzlichen Dank für all deine Beiträge! Einfach fantastisch und hochgradig interessant was du für Artikel und Bilder publizierst.

Vor ein paar Wochen waren wir in Chemnitz, wo keine Schweizer Touristen hingehen. Die gehen alle nach Dresden. Auf deiner Internetseite habe ich dann das Kaufhaus Schocken und Stadtbad entdeckt. Das Kaufhaus ist jetzt ja umfunktioniert, jedoch mit seiner hellen Fassade immer noch sehr beeindruckend von aussen. Früher, als all die alten dunklen Häuser drumherum standen muss des noch viel mehr der Fall gewesen sein. Das Stadtbad konnten wir leider nur von aussen, da geschlossen, betrachten. Mit seiner Klarheit ebenfalls einmalig und beispiellos. Wir waren nicht das letzte Mal in Chemnitz, der europäischen Kulturhauptstadt 2025.

Ich freue mich auf viele weitere Artikel von dir!

Gruss aus der Schweiz

Benno

Servus Benno

Das freut mich sehr! Chemnitz ist immer eine Reise wert und es gibt viel zu entdecken.

Herzliche Grüße