Einsteinhaus, 1929. Architect: Konrad Wachsmann. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Einsteinhaus, 1929. Architect: Konrad Wachsmann. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Einsteinhaus, 1929. Architect: Konrad Wachsmann. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Einsteinhaus, 1929. Architect: Konrad Wachsmann. Photo: Daniela Christmann

1929

Architect: Konrad Wachsmann

Am Waldrand 15-17, Caputh, Germany

In 1929, the Einstein House was built for Albert Einstein in Caputh, Brandenburg, according to plans by architect Konrad Wachsmann.

Both Albert and Elsa Einstein, their daughters and a maid lived in the house from 1929 to 1932.

Background

Gustav Böß, the mayor of Berlin, had the idea in 1929 to give the Nobel Prize winner and the city’s most famous scientist Albert Einstein a plot of land on the waterfront for his fiftieth birthday.

Böß was particularly committed to the construction of playgrounds and sports facilities and the creation of parks. During his tenure, the Post Stadium, the German Sports Forum, the sports fields in Charlottenburg, on the edge of Grunewald and in Volkspark Jungfernheide, the Dominicus sports field in today’s Schöneberg Sports Center and the Mommsen Stadium were built.

During his time, there were also major construction projects such as the Berlin Trade Fair and Tempelhof Airport, as well as the Berlin in Light campaign week from October 13 to 16, 1928.

Konrad Wachsmann

While the city administration was on the lookout for a suitable piece of land, the twenty-seven-year-old architect Konrad Wachsmann, who had been employed as a senior architect at the construction company Christoph & Umack in the Saxon town of Niesky since 1926, discovered a newspaper notice in the morning mail.

A note announced that the city of Berlin would donate a plot of land to Albert Einstein on which, according to his wishes, a wooden house was to be built.

At that time, the company Christoph & Unmack was a leader in the industrial production of wooden houses.

After reading the article, Wachsmann made the decision to plan and realize Einstein’s house.

He looked up Einstein’s address in the telephone book and drove to his apartment at Haberlandstraße 5 in Berlin on the same day.

Elsa Einstein

Wachsmann succeeded in convincing Elsa Einstein of his intention and together they visited a plot of land offered by the city.

While driving there, Elsa described what she and her husband were looking for: a house with French windows, terraces and a dark red tiled roof. Apart from the living room, which would have to have a fireplace, all the rooms in the house were to be small.

Wachsmann, a staunch advocate of modernism, had to take the clients’ rather conservative ideas into account in his designs.

Details such as the hipped roof with tiled roofing, the protruding cross beams, and the French windows met the wishes of the clients. In terms of modern construction techniques, wooden cladding, the spacious roof terrace, and the functional interior design, Wachsmann was able to hold its own.

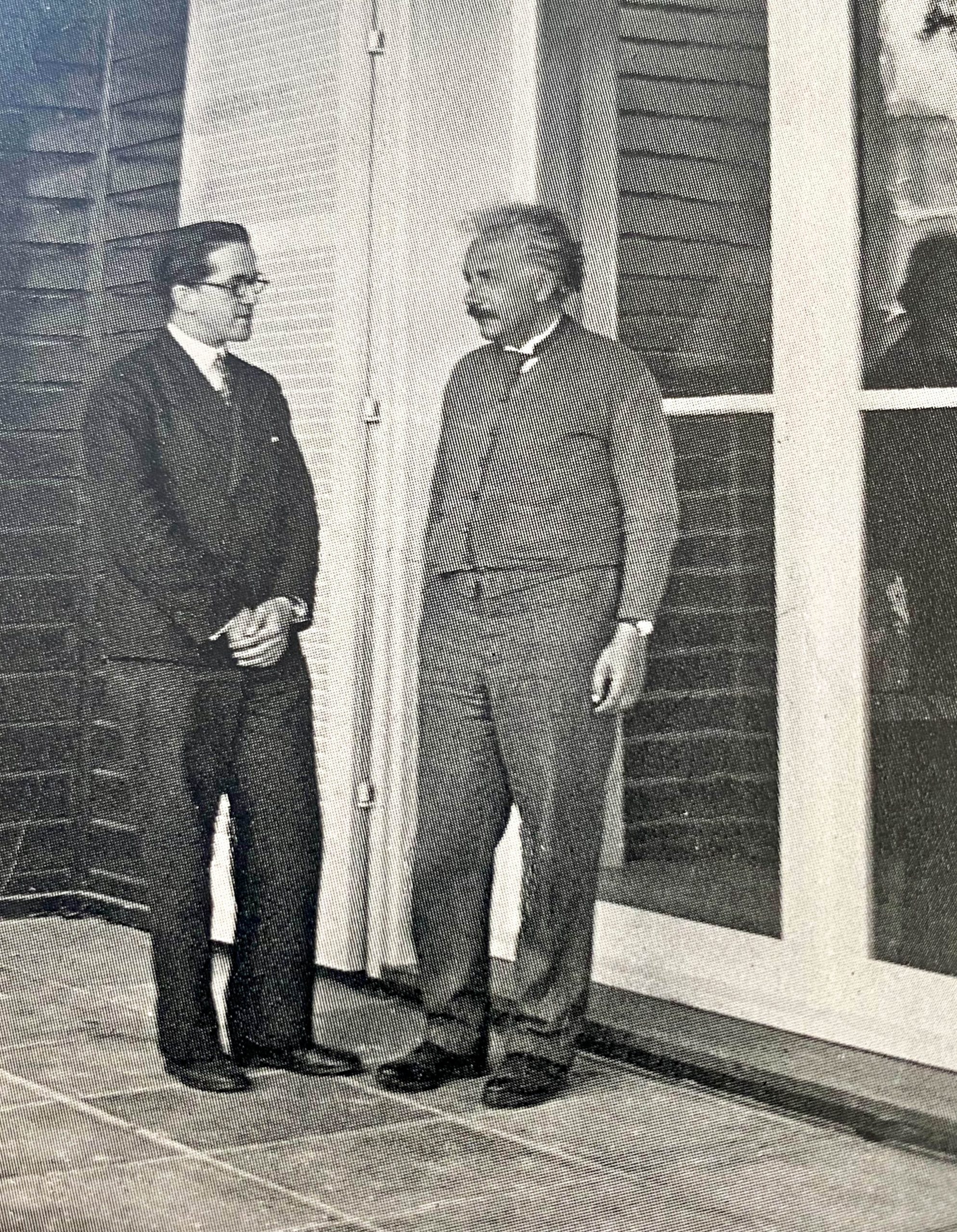

Albert Einstein and Konrad Wachsmann on the terrace of the Einstein House, 1929.

Construction

Friends of the family, who had heard about the Einsteins’ search for land outside Berlin, offered to sell part of their land in Caputh, located on Lake Templin and Lake Schwielow, for the construction of the house.

Located on a hill at the edge of the forest, the property overlooked Lake Templin, which was a ten-minute walk away.

Einstein inspected the property and decided the same day to buy it with his own funds.

On May 12, 1929, Einstein signed the construction documents, officially concluding the contract with Christoph & Unmack. On the same day, Wachsmann applied for a building permit, which was issued in mid-June.

While the house’s foundation was being laid on site, workers at Christoph & Unmack erected the house’s construction kit in a company-owned industrial hall in July.

As soon as the engineers had approved the construction, it was disassembled back into its individual parts and packed together with the remaining building materials and shipped to Berlin.

At the construction site, it took workers two weeks to complete the shell and cladding of the facade. Another two weeks were planned for the interior work, and by September 1929 the summer house was ready for occupancy.

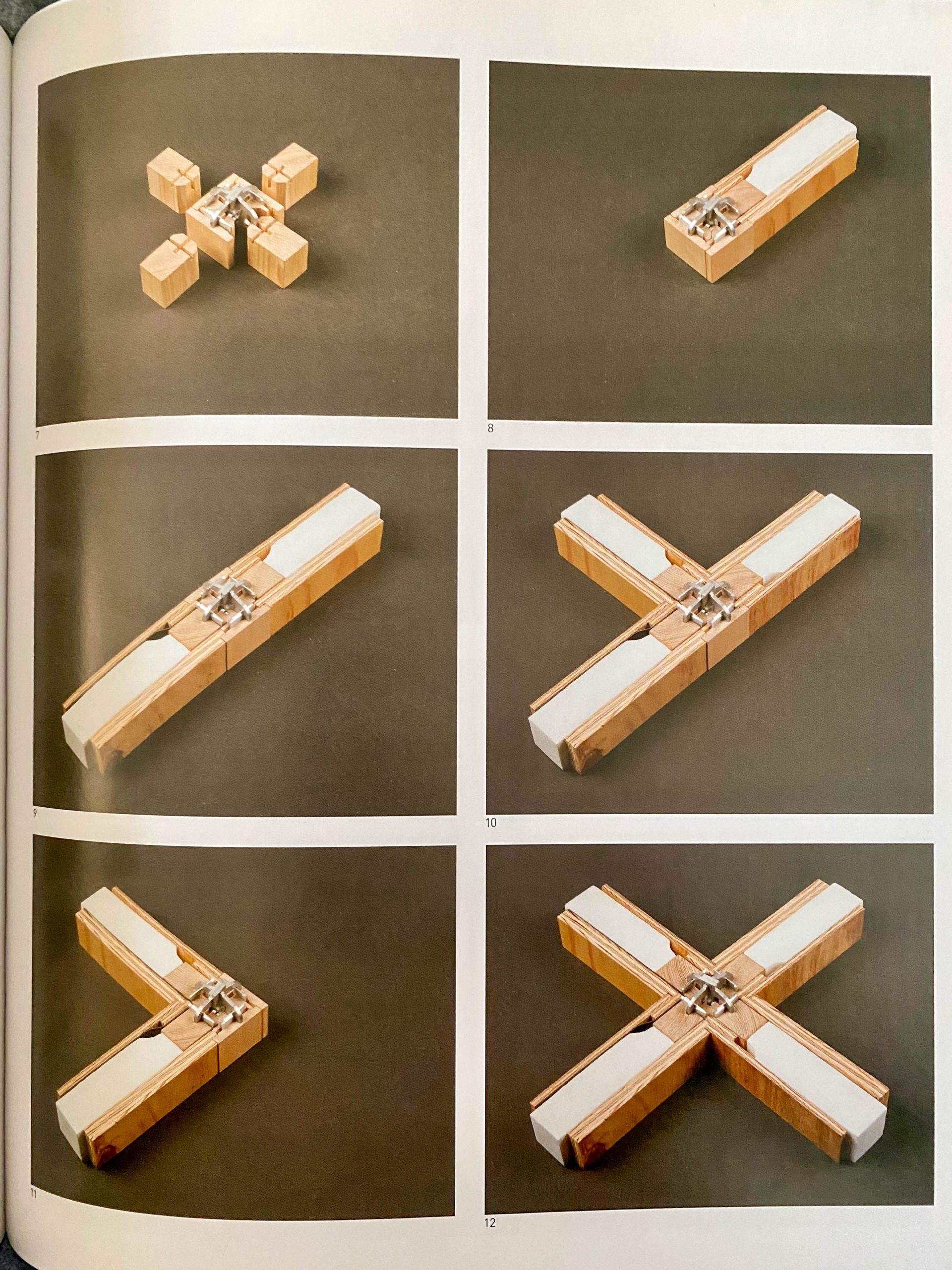

General Panel System. Konrad Wachsmann and Walter Gropius, 1941

Sommerhaus

It is a one- to two-story wooden house over an L-shaped ground plan, executed in truss-and-column construction (balloon frame system).

Externally, the house is characterized by horizontal boarding of dark-painted North American Douglas fir.

There are few windows on the street side, but on the garden side the house opens wide to the landscape. From the roof terrace a staircase leads to the garden.

Situated in the garden to the southwest of the summer house is the one-story garden house, also made of wood, which is now used as summer accommodation for visiting scientists.

Inside the summer house on the first floor on the street side is the kitchen and hallway with a staircase to the upper floor. A spacious living room, a bathroom and a bedroom are located on the west-facing side of the garden, and Albert Einstein’s study is located to the south.

The upper floor housed the daughters’ bedrooms, the maid’s room, and guest rooms.

Gardenhouse. Einsteinhaus, 1929. Architect: Konrad Wachsmann. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Interior

Numerous interior details have survived to the present day, including the interior doors, the black and white tile flooring in the hallway, kitchen, and bathroom, the fireplace in the living room, the built-in kitchen with pass-through, and the built-in cabinets in the private rooms.

Together with his wife Elsa, Einstein lived in the wooden house, originally designed as a summer residence, almost year-round between 1929 and 1932.

The house provided the ideal starting point for sailing trips on the Havel with his wooden boat “Tümmler”.

From April to November, he left the house only to attend lectures or make public appearances.

Einstein regularly invited scientists, political activists, writers, philosophers, journalists and artists to visit him in Caputh.

Einsteinhaus, 1929. Architect: Konrad Wachsmann. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Einsteinhaus, 1929. Architect: Konrad Wachsmann. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Einsteinhaus, 1929. Architect: Konrad Wachsmann. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Einsteinhaus, 1929. Architect: Konrad Wachsmann. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Einsteinhaus, 1929. Architect: Konrad Wachsmann. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Einsteinhaus, 1929. Architect: Konrad Wachsmann. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Einsteinhaus, 1929. Architect: Konrad Wachsmann. Photo: Daniela Christmann

The house in the years after 1932

On December 6, 1932, the Einsteins left Caputh to travel to Pasadena in the United States, where Einstein gave guest lectures at the California Institute of Technology for two months.

Between April and May 1933, after Hitler came to power, Einstein’s accounts were confiscated, his sailboat seized, and his apartment ransacked.

Since the notarial deed to the house in Caputh was in the name of his stepdaughters, it was initially spared.

From America, the Einsteins asked a lawyer friend to rent the house to a Jewish children’s home in the neighborhood.

After Einstein’s German citizenship was officially revoked in 1934, the property was confiscated on January 10, 1935.

Renovation

Despite changing uses, the house survived the war years without significant damage.

Shortly before Einstein’s death in April 1955, the house was listed as a historical monument.

In 1978, the Academy of Sciences of the GDR was appointed the official custodian, receiving a substantial sum to renovate the house.

On the centenary of Einstein’s birth in 1979, the house was opened to the public.

After the dissolution of the Academy of Sciences of the GDR in 1991, the house was returned to the municipality of Caputh, which in turn gave it to the state of Brandenburg.

Current Use

The Einstein House remained open to the public two days a week during the 1990s before humidity problems on the roof and the general state of the house in need of repair made closure unavoidable in 2001.

Plans for extensive repair work were made while the repair work was still being carried out.

One of the main issues after the reunification of Germany concerned ownership. After lengthy legal disputes, it turned out that the house belonged to a community of heirs and that the Hebrew University in Jerusalem was the main owner of the house.

The legal heirs were entered in the land register in 2004.

The house was reopened in May 2005 after a thorough renovation.

It is managed by the Einstein Forum Potsdam, which uses it as a venue for events and makes it accessible to the public.