1923 – 1925

Architect: Robert Mallet-Stevens

47 Montée de Noailles, Hyères, France

In the spring of 1923, French aristocrat, patron, and art collector Charles de Noailles commissioned architect Robert Mallet-Stevens to design a villa for him above Hyères in the south of France.

Villa Noailles, 1923-1925. Architect: Robert Mallet-Stevens. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Villa Noailles. Picture postcard, 1929

Charles de Noailles

Originally, Charles de Noailles had planned a small residence on the Côte d’Azur for the winter months, which he intended to transform into a gathering place for the avant-garde. By that time, he had already amassed an extensive collection of modern paintings, including works by Pablo Picasso, Juan Gris, Marc Chagall, Max Ernst, and Joan Miró.

He also supported artists such as Man Ray, Luis Buñuel, and Marcel L’Herbier, who were experimenting with film as a new medium.

De Noailles financed Man Ray’s film Les Mystères du Château de Dé (1929), which revolves around the Villa Noailles in Hyères. De Noailles also supported Jean Cocteau’s film Le Sang d’un Poète (1930) and Luis Buñuel’s L’Âge d’Or (1930), which was co-written by Salvador Dalí.

Charles und Marie Laure de Noailles, 1929. Villa Noailles Private Collection

Marie-Laure de Noailles

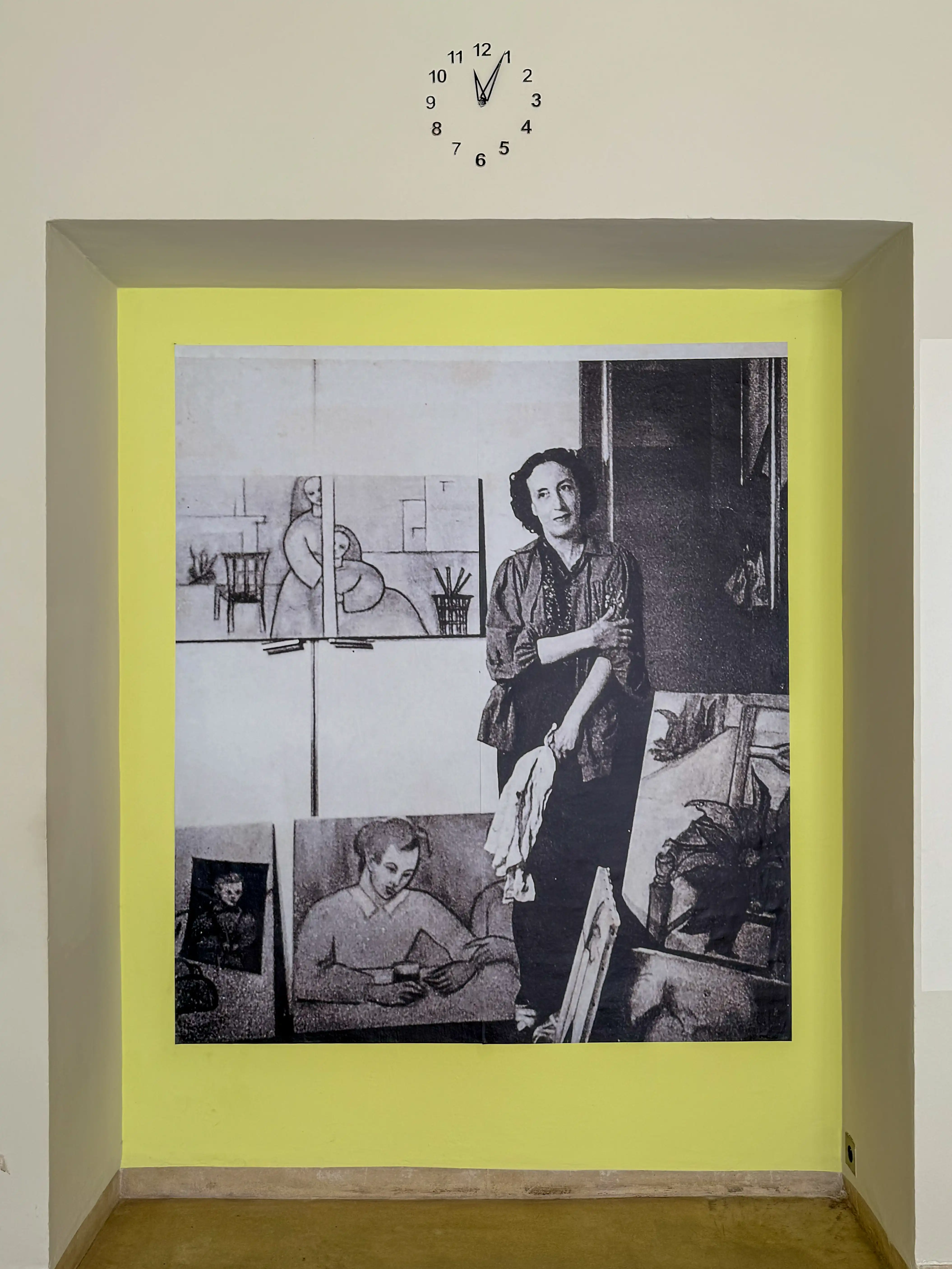

Marie-Laure Vicomtesse de Noailles was a writer, poet, painter, art collector, and patron of the avant-garde.

The only child of Parisian banker Maurice Bischoffsheim and his wife, Marie-Thérèse de Chevigné (daughter of Comte Adhéaume de Chevigné and Laure Marie Gabrielle de Sade), she was born in Paris in 1902.

Marie-Laure never met her father, who died of tuberculosis when she was still a child. A family council initially managed her large fortune.

She spent her youth in a sophisticated, educated environment. She spent her summers at the Villa Croisset in Grasse. She was friends with Jean Cocteau since childhood and remained in love with him throughout her life, albeit intermittently.

On February 9, 1923, Marie-Laure married Charles de Noailles, the second son of François de Noailles, Prince de Poix, and his wife, Madeleine-Marie Dubois de Courval, in Paris. The couple had two daughters.

Marie-Laure de Noailles. Photo from the Villa Noailles exhibition.

Robert Mallet-Stevens

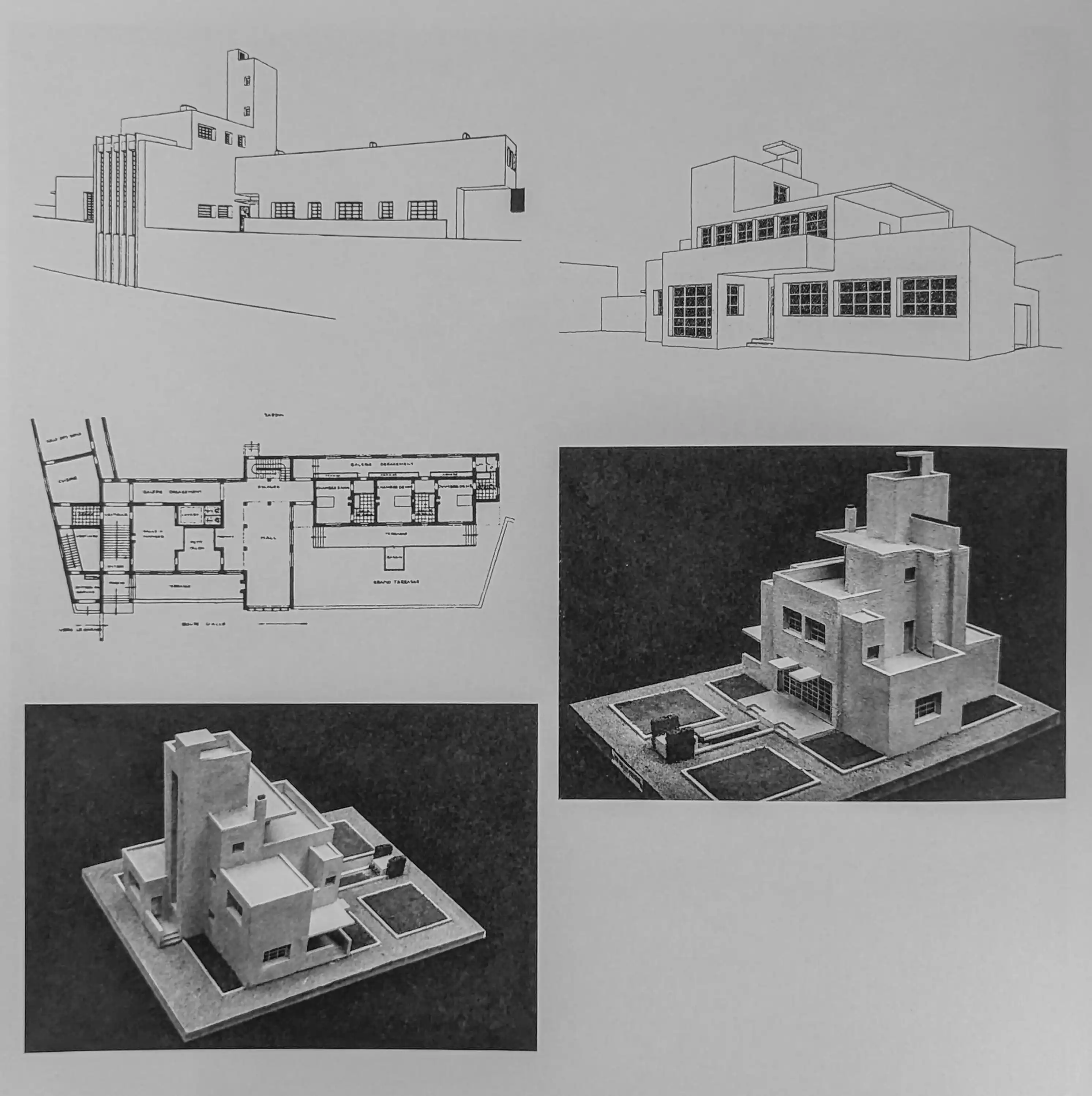

The new building project in Hyères was planned from the beginning as a modernist manifesto. For this reason, Charles de Noailles traveled to the Bauhaus in Weimar, made contact with Mies van der Rohe, and negotiated with Le Corbusier.

In 1922, at the Salon d’Automne in Paris, de Noailles met Robert Mallet-Stevens, who presented the model of his “Pavillon de l’Aéro-Club” there.

Until then, Mallet-Stevens had only made a name for himself with film decorations, but he seized the opportunity to work as an architect for the first time.

Property

For his wedding on February 9, 1923, Charles de Noailles received a plot of land measuring approximately 1.5 hectares from his mother, Madeleine Dubois de Courval. The land was located near Hyères. The ruins of the Saint-Bernard monastery were located on the property. These were overlooked by the remains of the castle of the Counts of Provence, which was razed in the 11th century.

Villa Noailles, 1923-1925, architect: Robert Mallet-Stevens. Contemporary photo

Project

Charles and his wife, Marie-Laure de Noailles, commissioned Mallet-Stevens to design a villa between the walls, terraced gardens, and ruins.

The experienced local architect, Léon David, was entrusted with on-site construction management and essential parts of execution planning.

Design

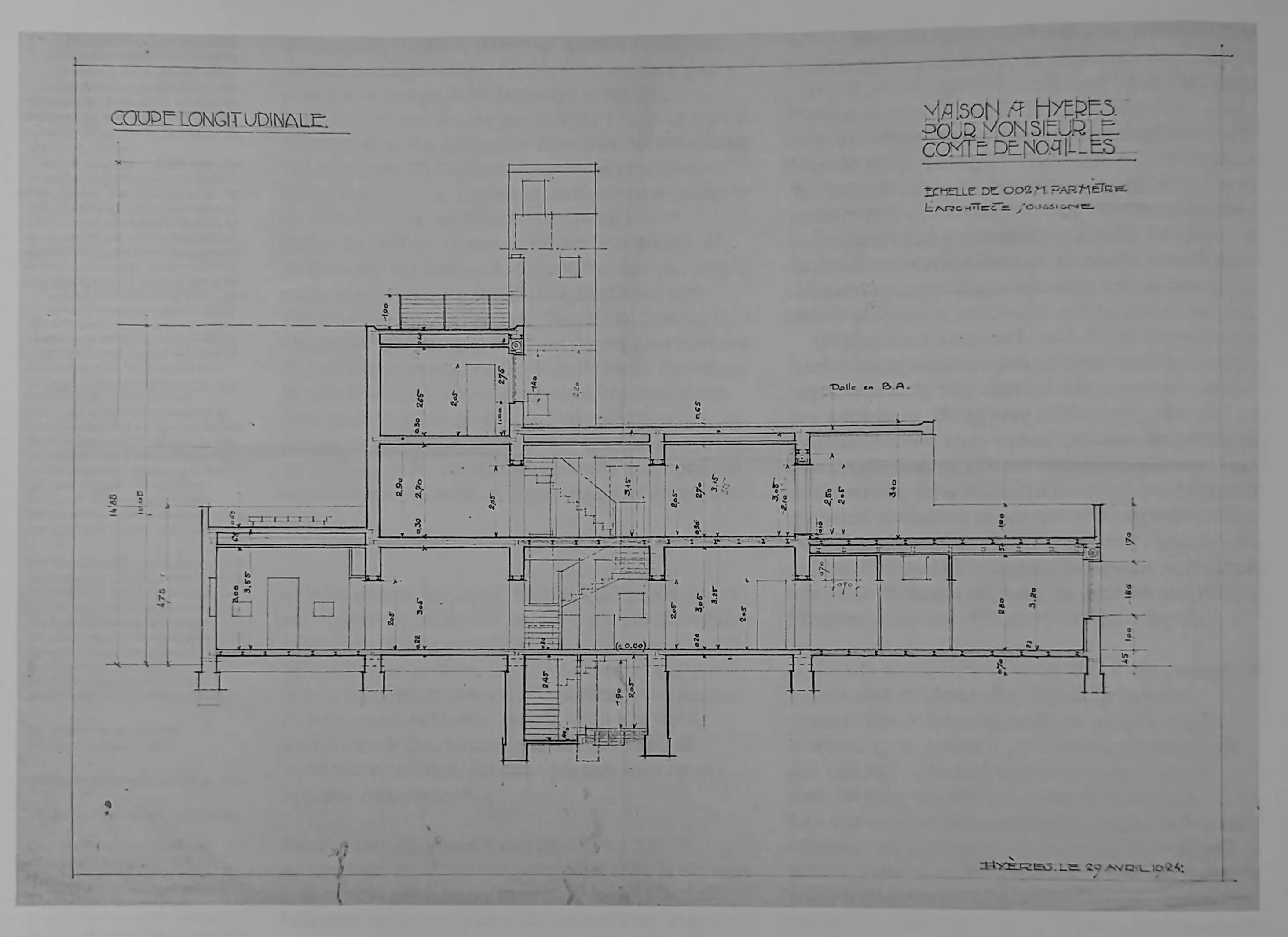

The first drafts of the project, created in January 1924, show how the new building is integrated into the existing structure.

The villa’s design consists of a composition of rectangles, cubes, and prisms arranged in a strictly geometric fashion.

A vertical core containing the main staircase forms the central point of the complex and is surmounted by a high stair tower with a belvedere.

A footpath runs alongside the villa and gardens, and a driveway for cars runs one level below along the retaining wall of the former Cistercian vault. Both lead to the villa.

Villa Noailles, 1923-1925. Architect: Robert Mallet-Stevens

Villa Noailles, 1923-1925. Architect: Robert Mallet-Stevens

Villa Noailles, 1923-1925. Architect: Robert Mallet-Stevens. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Construction

The geometric blocks, expansive window openings, and projecting canopies, balconies, and gargoyles create the illusion of a reinforced concrete structure.

In reality, however, the building was constructed using traditional brick-and-stone methods. Concrete was only used to support the wide openings, beams, and cantilevered elements.

The plaster is a mortar made with on-site aggregates. Consequently, the light yellow to sand-colored tint matched the walls of the terraces and ruins.

Villa Noailles, 1923-1925. Architect: Robert Mallet-Stevens. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Villa Noailles, 1923-1925. Architect: Robert Mallet-Stevens. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Villa Noailles, 1923-1925. Architect: Robert Mallet-Stevens. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Villa Noailles, 1923-1925. Architect: Robert Mallet-Stevens. Photo: Daniela Christmann

A Modern House — Small and Simple

In his letters to Robert Mallet-Stevens, the client repeatedly emphasized that he wanted a small, simple house. All elements were to be derived exclusively from their functions, with nothing serving the purpose of representation or the celebration of a “côté architecturale.”

In this case, “small” meant 200 square meters of living space, and “simple” meant unconditional functionality. The client said, “I want to build an extraordinarily modern house. By modern, I mean using all modern means to achieve maximum efficiency and comfort.” (Cécile Briolle, Agnès Foisnet, and Gérard Monnier: La Villa Noailles, Paris, 1990, p. 22).

Villa Noailles, 1923-1925. Architect: Robert Mallet-Stevens. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Villa Noailles, 1923-1925. Architect: Robert Mallet-Stevens. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Villa Noailles, 1923-1925. Architect: Robert Mallet-Stevens. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Villa Noailles, 1923-1925. Architect: Robert Mallet-Stevens. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Completion

The house was completed in November 1925 based on the initial design from 1923. This allowed the Noailles to spend their first winter there.

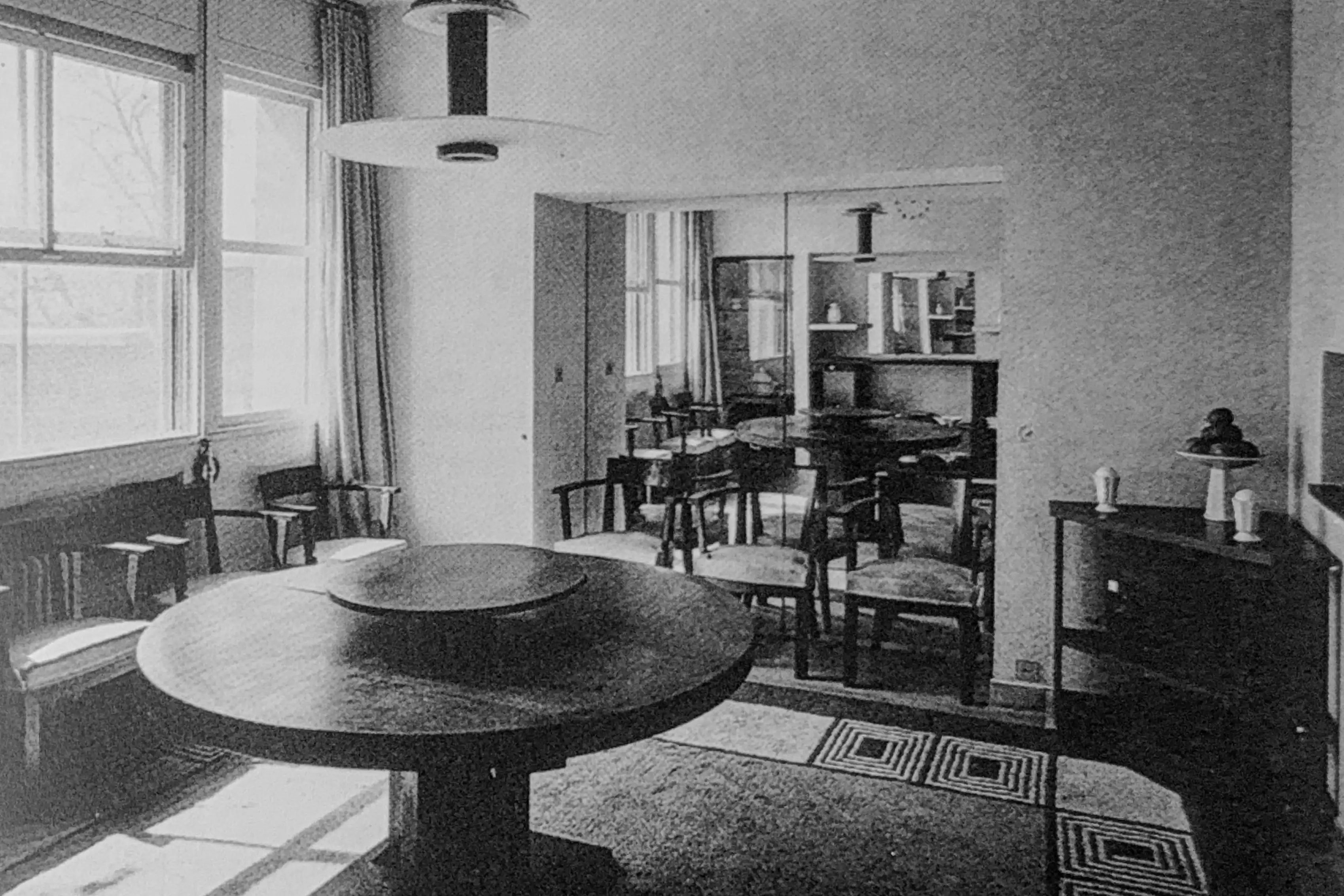

All of the rooms faced south and were as small as possible. The reception rooms were only the size of an upper-class apartment.

The drawing room measured 21 square meters, and the dining room measured 17. Only the vaulted ceilings of the former monastery were spacious. They had been carefully restored.

Extensions

Soon after the initial design of the villa was completed, it became clear that extensions were unavoidable. The dining room on the first floor was almost doubled in size, and a kitchenette was added. Three additional guest apartments, comprising a total of five rooms, were also carved into the hillside.

Dining room extension with furniture by Georges Djo-Bourgeois, 1928

Salon Rosé

A square room measuring 50 square meters was also built into the retaining walls on the slope side in 1926/27. Since it is below ground, it is lit exclusively from above. The previous salon proved to be too small for the lavish parties.

The underground room, known as the “Salon Rosé” because of its rose-colored walls, has a flat, simply plastered ceiling in the first third.

The salon then reaches its full height in the next two thirds and is fitted with a suspended glass ceiling inserted between box girders made of welded sheet steel. This construction is suspended from a steel framework that supports a north-facing, fully glazed monopitch roof.

Salon Rosé, Villa Noailles. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Salon Rosé, Villa Noailles. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Salon Rosé, Villa Noailles. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Glass Ceiling

The inner glass ceiling is divided into five perpendicular fields located at different heights within the beam. These fields are closed with opaque, monochrome glass. The geometric composition of the ceiling continues onto the walls in the form of a relief.

Salon Rosé, Villa Noailles. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Salon Rosé, Villa Noailles. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Furnishings

The furnishing of Villa Noailles began before the first phase of construction was completed in 1925.

Since the villa was conceived as a complete work of art, all the furniture and design elements were created according to a consistent concept and color scheme.

Architect Mallet-Stevens commissioned artists and architects with whom he had previously collaborated on film set designs or exhibitions.

These artists and architects included Georges Djo-Bourgeois, Pierre Chareau, Eileen Gray, Louis Barillet, Theo van Doesburg, Alberto Giacometti, Jan and Joël Martel and Sybold van Ravensteyn.

Alberto Giacometti : Applique main (main et coupe droite, main et coupe gauche), Plaster, 1931. Jan et Joël Martel : Polyhedral mirror. Photo : Daniela Christmann

Alberto Giacometti: Applique main (hand and right cup), plaster, 1931. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Jan and Joël Martel: Polyhedral mirror, Villa Noailles. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Petite Chambre des Fleurs

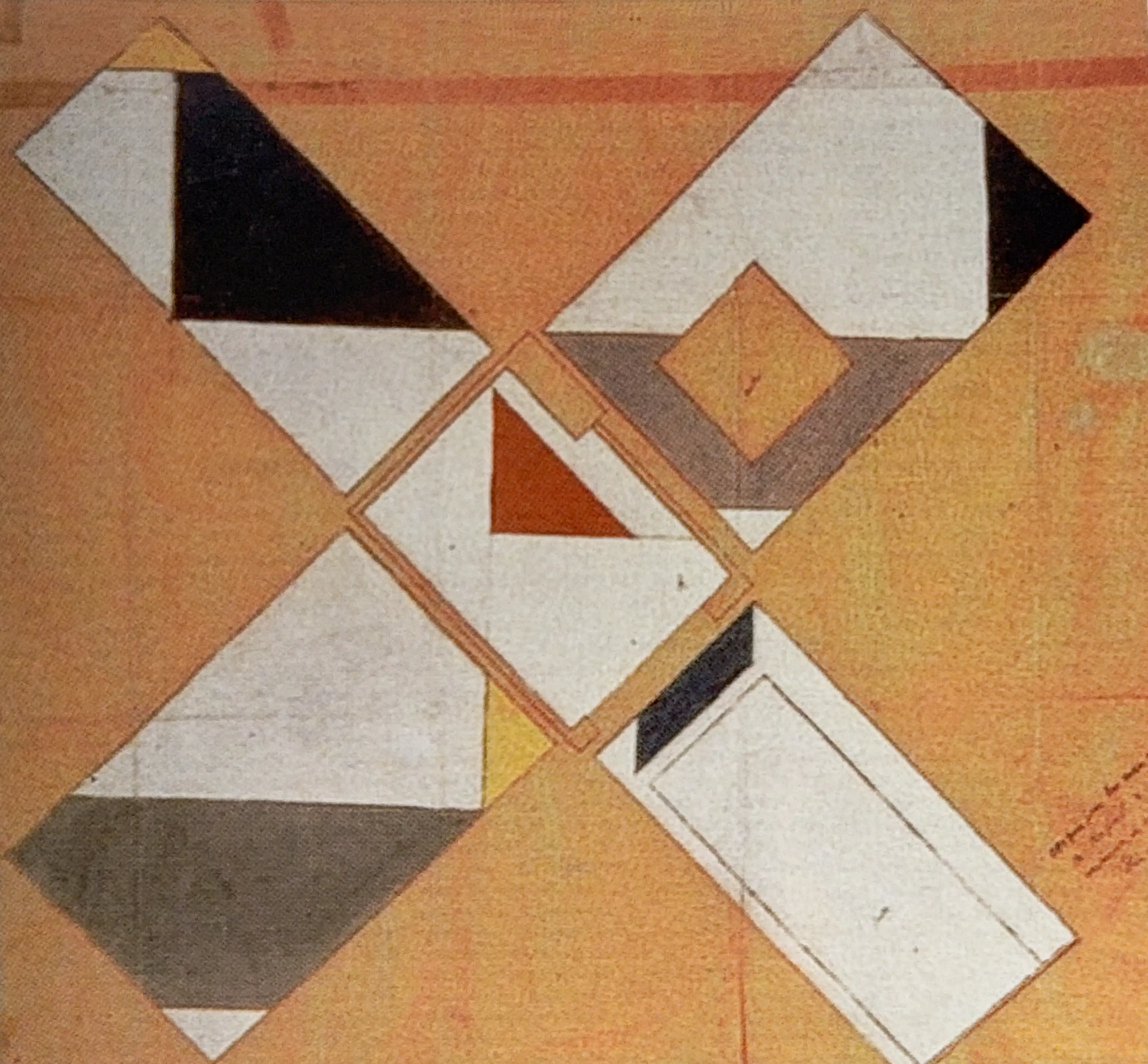

Theo van Doesburg was commissioned to paint the “Petite Chambre des Fleurs,” a room measuring less than two square meters where the villa’s flower arrangements were assembled.

Van Doesburg designed an abstract composition of colored triangles on the walls and ceiling that is laid out independently of the room’s architectural features, such as the windows and doors.

Small Room of Flowers at Villa Noailles. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Small Room of Flowers at Villa Noailles. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Wall development of the ‘Petite Chambre des Fleurs’ by Theo van Doesburg, 1924-1925

Building Services

Charles de Noailles, the client, attached particular importance to the technical equipment of the villa. Apart from the central heating installation, the bathroom building services were developed by the English engineer Thomas Lowe, who was based in Nice.

After 1926, the house was fitted with floor-to-ceiling glass windows and doors that could be lowered into the floor. Simple doors were replaced with sliding walls or doors.

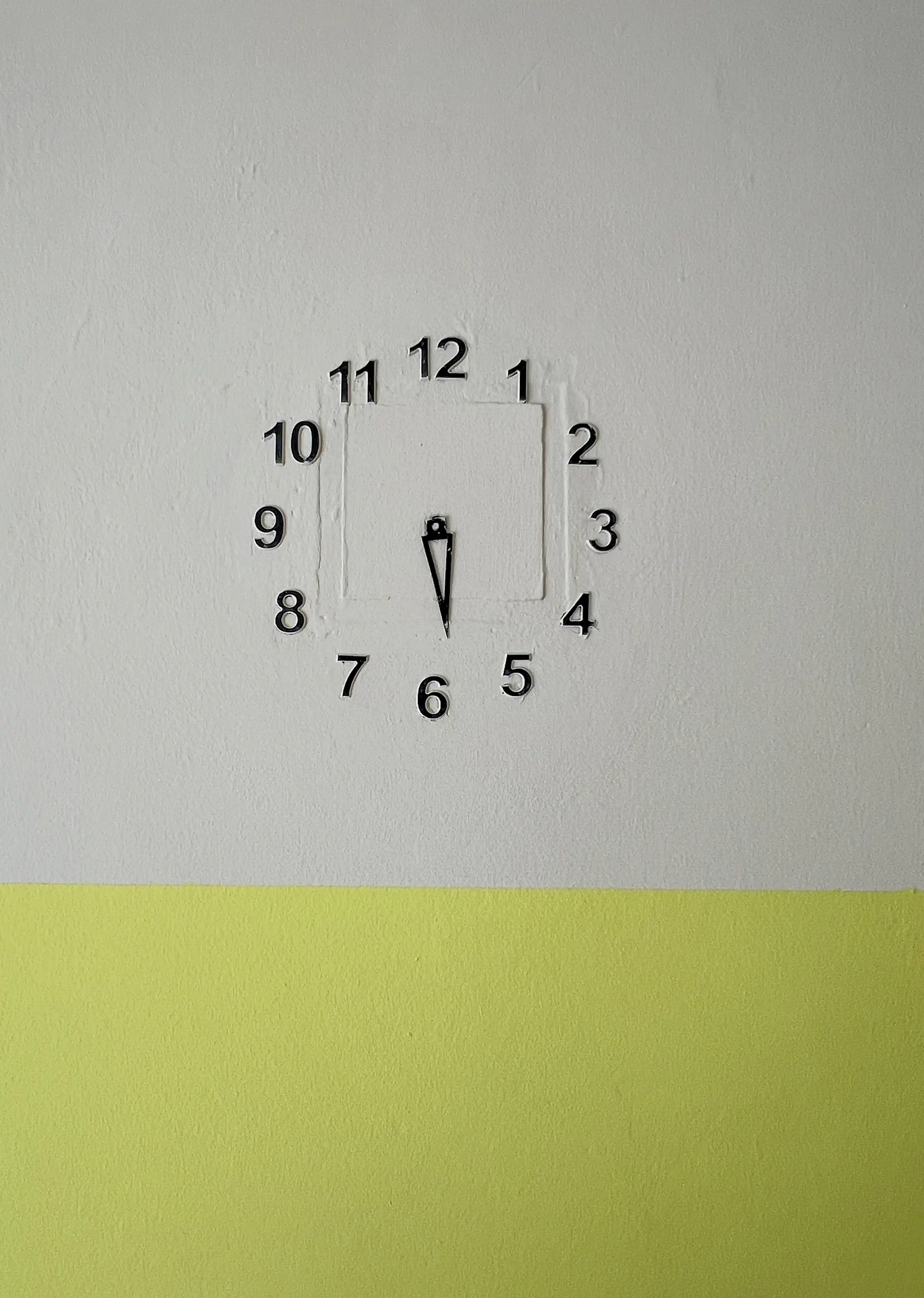

In 1925, de Noailles also had fourteen identical clocks installed. The electric clockwork is recessed into the wall, leaving only the 25-centimeter dial visible. Francis Jourdain designed the dial. A central control system ensured that the same time was displayed in all rooms.

Wall Clock. Design: Francis Jourdain. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Wall Clock. Design: Francis Jourdain. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Open-Air Room

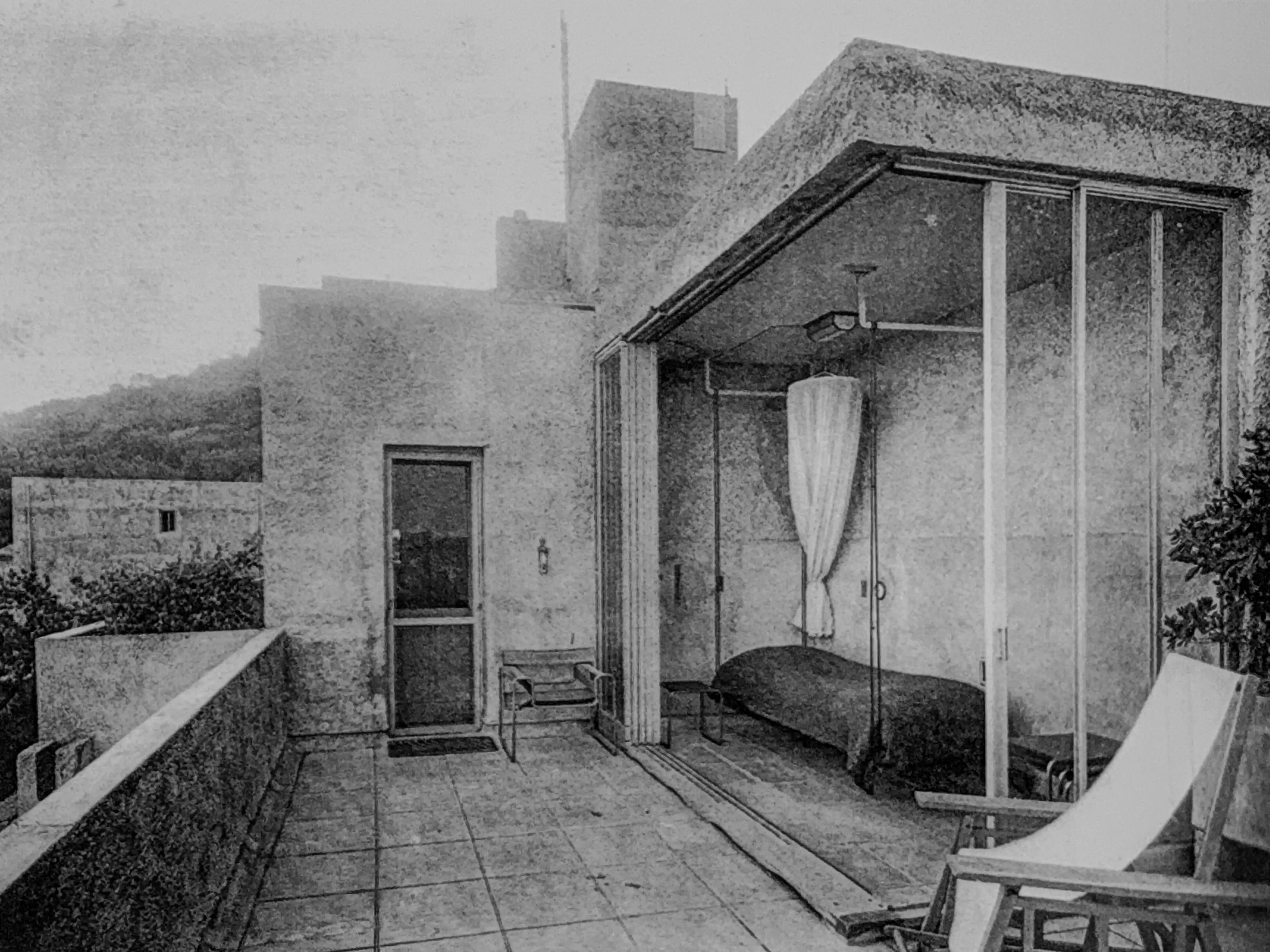

The gentleman’s apartment also had an open loggia that could be closed off with sliding glass doors. A bed hung from the cantilevered ceiling panel in this loggia, attached with ropes.

This open sleeping area, furnished with pieces designed by Pierre Chareau, was reminiscent of life aboard a ship. These included a balançoire bed, which was suspended from four attachment points and could compensate for a ship’s rolling motion in its original function, as well as a tropical mosquito net. The other furniture in the loggia was a Wassily chair and a canvas armchair, both of which were designed by Marcel Breuer.

A staircase led directly from the loggia to the north garden.

Open-air room at Villa Noailles, 1928. Photo: Thérèse Bonney

Villa Noailles, 1923-1925. Architect: Robert Mallet-Stevens. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Hanging Garden

The 500-square-meter Hanging Garden is located on the three barrel-vaulted rooms of the former monastery. Six rectangular openings cut into the nearly four-meter-high wall give the view the appearance of a series of framed pictures.

Villa Noailles, 1923-1925. Architect: Robert Mallet-Stevens. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Cubist Garden

The Cubist triangular garden was designed by Gabriel Guévrékian and constructed from 1926 to 1927.

In 1925, Charles de Noailles visited the “Jardin d’eau et de lumière,” designed by Guévrékian for the “Exposition des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes” in Paris.

Similar to the 1925 exhibition, the land designated for the Villa Noailles garden was a triangular area on the narrow side of the house.

Guévrékian added a wall to the third side of the plot, creating a sunken garden shaped like a ship’s bow with strict boundaries. The area is divided into square and rectangular fields.

In the upper corner, a water basin set into the ground was intended to hold a figure. However, the intended location was too small for the 2.25-meter-high, gilded bronze “Joie de Vivre” by Jacques Lipchitz, which Charles de Noailles had purchased for this purpose. This is why it was placed at the top of the garden.

Cubist garden, Villa Noailles. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Marie-Laure and Charles de Noailles posing in front of the Bronze ‘Joie de Vivre’ by Jacques Lipchitz

Cubist garden, Villa Noailles. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Cubist garden, Villa Noailles. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Cubist garden, Villa Noailles. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Reception

The villa was initially barely noticed by critics, but became famous overnight when Man Ray shot the silent film Les Mystères du Château du Dé there in January 1929. In it, he combined his surrealist narratives with the architecture of the house.

The title of the film, ‘The Mysteries of the Castle of Dice’, alludes to dice as a symbol of chance determining the course of events.

Current Use

The villa was sold to the municipality in 1973 and remained empty for a long time, falling into disrepair. It was added to the list of listed buildings in 1975 and 1987.

Architectural firm Cécile Briolle, Claude Marro and Jacques Repiquet then restored the building in several stages, converting it into an art and architecture centre in 1996.

Today, it hosts temporary exhibitions on art, architecture, design, photography and fashion. The villa has been open to the public since 1989.