Siedlung Bruchfeldstrasse, 1926-1927. Planning: Ernst May, Herbert Boehm. Photo: Daniela Christmann

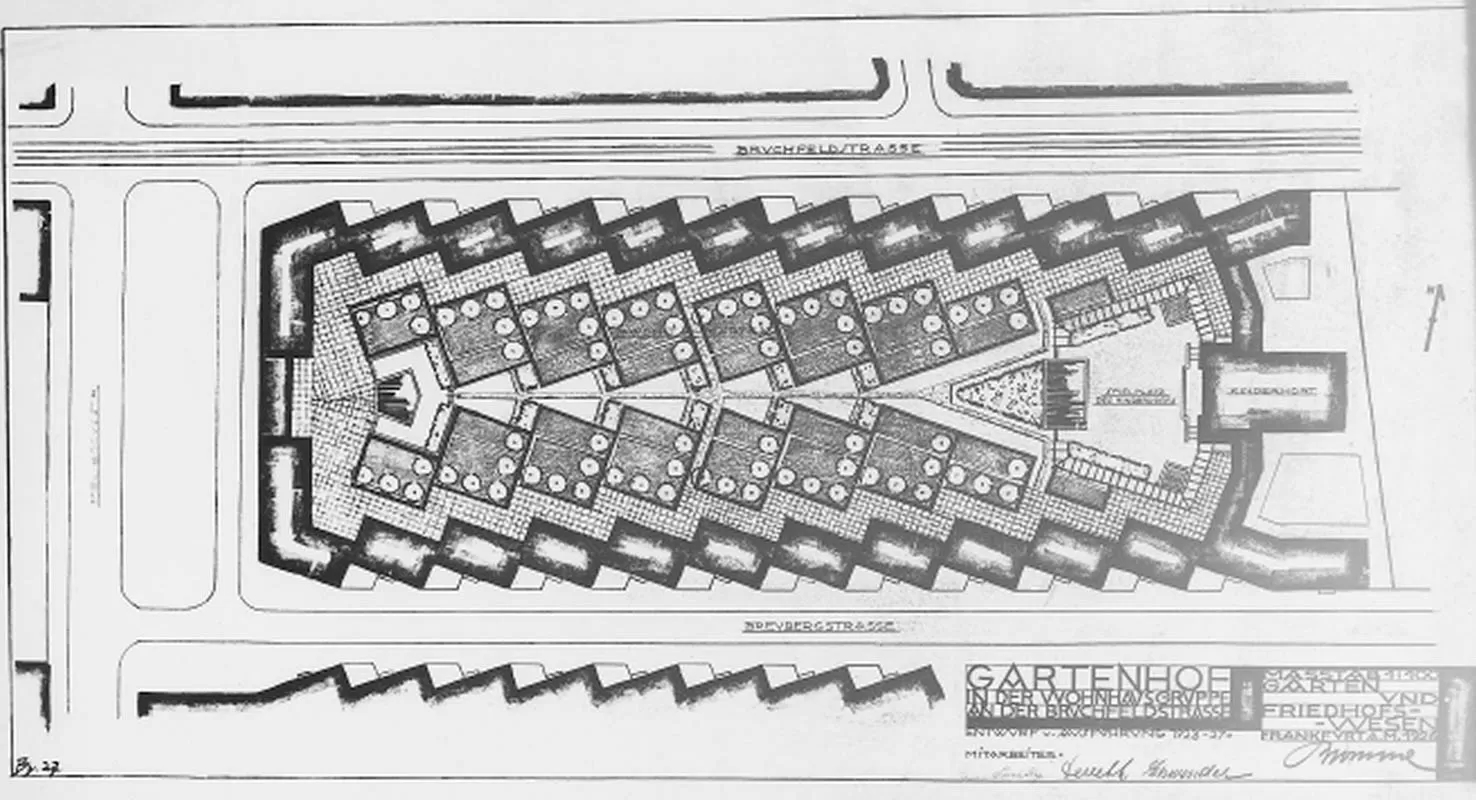

Siedlung Bruchfeldstrasse, 1926-1927. Planning: Ernst May, Herbert Boehm

Siedlung Bruchfeldstrasse, 1926-1927. Planning: Ernst May, Herbert Boehm. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Siedlung Bruchfeldstrasse, 1926-1927. Planning: Ernst May, Herbert Boehm

Siedlung Bruchfeldstrasse, 1926-1927. Planning: Ernst May, Herbert Boehm

Siedlung Bruchfeldstrasse, 1926-1927. Planning: Ernst May, Herbert Boehm. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Siedlung Bruchfeldstrasse, 1926-1927. Planning: Ernst May, Herbert Boehm. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Siedlung Bruchfeldstrasse, 1926-1927. Planning: Ernst May, Herbert Boehm. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Siedlung Bruchfeldstrasse, 1926-1927. Planning: Ernst May, Herbert Boehm

1926 – 1927

Overall planning housing estate: Ernst May, Herbert Boehm; Architects: Ernst May, Carl-Hermann Rudloff

Bruchfeldstrasse, Breubergstrasse, Donnersbergstrasse, Frankfurt am Main-Niederrad, Germany

Housing Estate

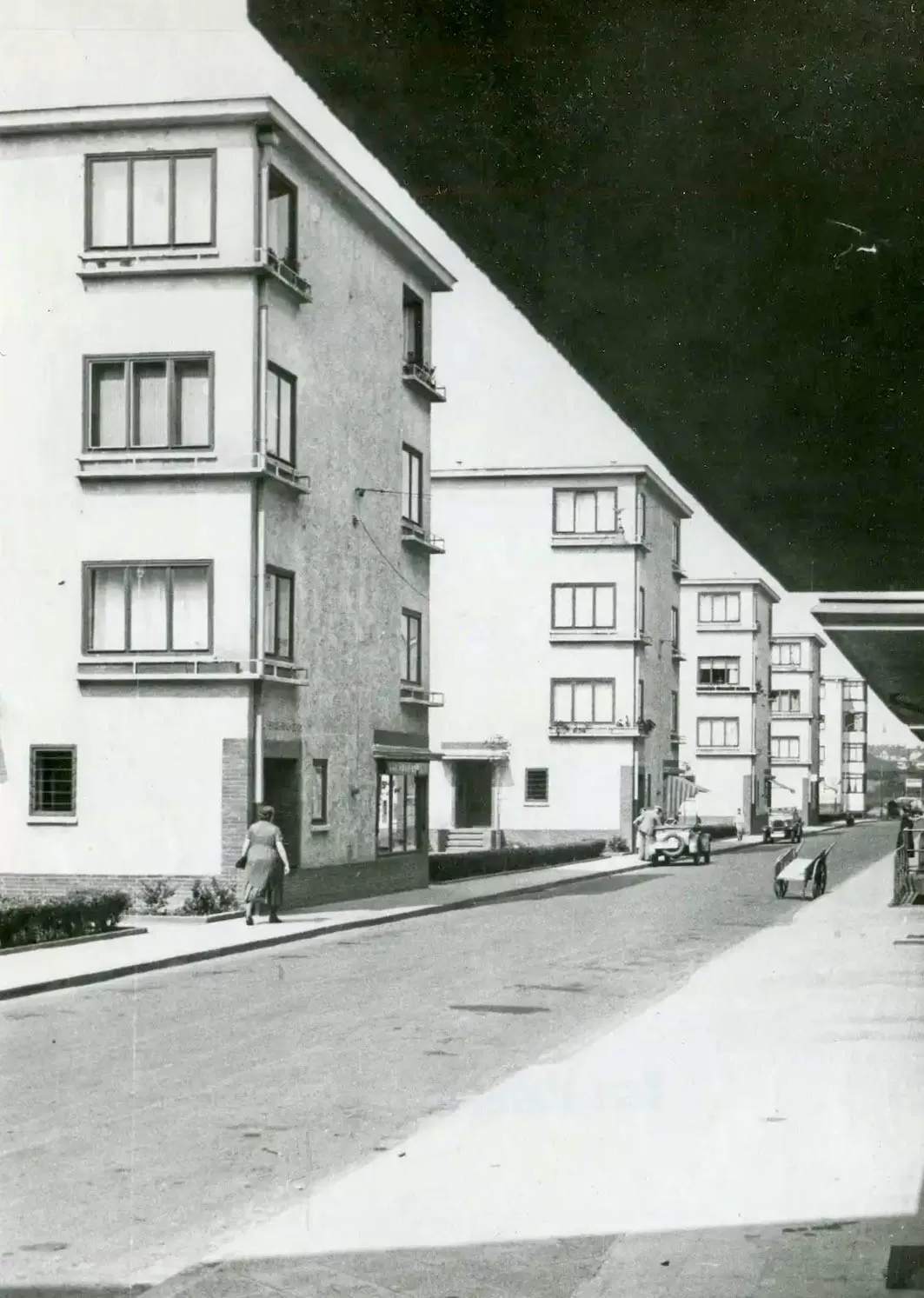

The Bruchfeldstrasse housing estate, popularly known as Zickzackhausen, was built between 1926 and 1927 in Frankfurt-Niederrad according to plans by architects Ernst May and Carl-Hermann Rudloff.

It is one of the first completed housing estates of the New Frankfurt and comprised 643 apartments in total. The developer was the Aktienbaugesellschaft für kleine Wohnungen (ABG).

In total, mainly 2- and 3-room apartments with a size of 56 or 65 m² were built in multi-story buildings with flat roofs in conventional brick construction.

These also included 49 terraced single-family houses of the same floor plan type in the west of the development area near the railroad line.

Upon moving in, the tenants had to pay a one-time share of 700 to 1,200 Reichsmark.

With monthly rents of 48 to 88 Reichsmark, the regular burden was almost half of a worker’s wage, so that the first tenants were mainly white-collar workers and civil servants.

The housing estate was inserted into the already existing urban district on vacant lots. Consequently, different forms of development resulted, ranging from perimeter block development to rows of terraced houses.

Buildings

Most of the apartments are multi-family houses, only the section on Donnersbergstraße consists of single-family row houses.

Central residential block on Bruchfeldstraße is a classic perimeter block development with an enclosed courtyard.

To optimize the incidence of light, the buildings were offset in a zigzag pattern. This striking facade pattern gave the housing development its name.

Each of the three floors contained six apartments, and the attic floor under the flat roof was used for storage.

Siedlung Bruchfeldstrasse, 1926-1927. Planning: Ernst May, Herbert Boehm. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Siedlung Bruchfeldstrasse, 1926-1927. Planning: Ernst May, Herbert Boehm. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Design

Up to the lintel height of the first floor, the plinth surfaces of the houses were finished in dark pebble wash plaster. The facades were otherwise plastered white, with colored bands at the height of the attics.

All living spaces and the roof terraces were oriented towards the inner courtyard, where social life would take place.

The utility gardens located in the inner courtyard and assigned to the apartments were staggered and structured in a zigzag pattern. These were accessible only through the basement.

The second floor apartments had no garden of their own and possessed instead sun terraces whose light scaffolding of iron bars allowed them to stretch cloths and thus take sunbaths protected from the gaze of strangers.

A large water basin and playgrounds for the settlement’s children were located in the inner courtyard.

Each apartment was equipped with a Frankfurt kitchen.

Facilities

According to the lease agreement, the estate’s own central heating system for 600 apartments, a central laundry and the estate’s own radio station had to be used and paid for by the residents. These facilities were housed in a building located in the symmetry axis of the complex.

Ferdinand Kramer designed the furnishings of the kindergarten, which was also housed here, as well as those of most of the other communal facilities in the May housing estates.

Single-family row houses on Donnersbergerstrasse and Kalmitstrasse differ in height and in having pure white facades with sculptural, semi-circular breezeways with parapets for two dwelling units each.

Here, the facades are plastered white, while the window frames were painted in a rich colored tone.

In its urban conception as a closed self-sufficient unit with portal buildings and water areas in the inner courtyard, the residential courtyard Zickzackhausen is indebted to the residential buildings of Red Vienna and Taut’s Hufeisensiedlung in Berlin-Britz.

Siedlung Bruchfeldstrasse, 1926-1927. Planning: Ernst May, Herbert Boehm. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Siedlung Bruchfeldstrasse, 1926-1927. Planning: Ernst May, Herbert Boehm. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Siedlung Bruchfeldstrasse, 1926-1927. Planning: Ernst May, Herbert Boehm. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Conclusion

Ernst May succeeded in combining his extremely modern, purpose-optimized concept of living with an equally modern, identity-creating design in the Bruchfeldstraße housing estate.

The zig-zag staggering of the residential cubes gave the estate a distinctive and recognizable character.

Details such as the design of the walls and plaster surfaces through color and materials as well as the provision of roof terraces and utility gardens contributed significantly to the quality of living.

Identification of the residents with their settlement can already be seen in the fact that they gave the settlement the name Zickzackhausen as early as the 1920s.

One year after a CIAM conference was held in Frankfurt in October 1929 on the subject of “Housing for the subsistence level”, Ernst May took stock. Some 12,000 apartments for around 60,000 residents had been created within five years.

However, the onset of the world economic crisis made it impossible to continue the New Frankfurt, despite ever further optimization and typification of construction. The city had become increasingly indebted and political pressure was growing.

Postwar period

Between 1930 and 1934, May left Frankfurt to build settlements in the industrial cities of the Urals on behalf of the government in Moscow. After that he emigrated to Africa, where he worked again as an architect in Nairobi from the late 1930s. In 1954 he returned to Germany and took over the planning management of the settlement company Neue Heimat in Hamburg.

In the 1970s, the first of May’s housing estates in Frankfurt were listed as historic monuments. Following initial structural analyses in the 1980s, some of them have since been renovated in line with the requirements for monument preservation.