Rundbau, 1926-1928. Architect: Hermann Hussong

Rundbau, 1926-1928. Architect: Hermann Hussong

Rundbau, 1926-1928. Architect: Hermann Hussong

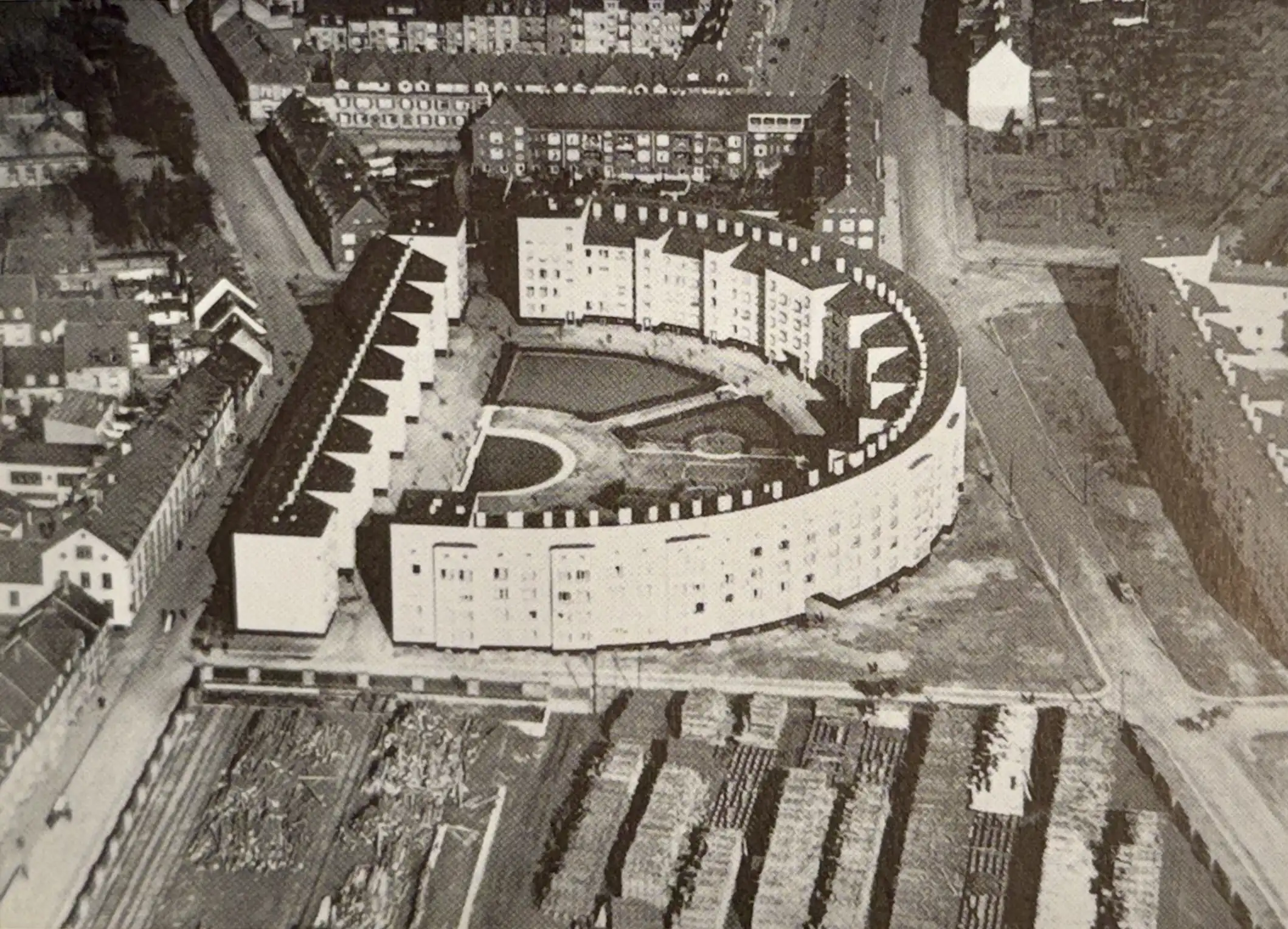

1926–1928

Architect: Hermann Hussong

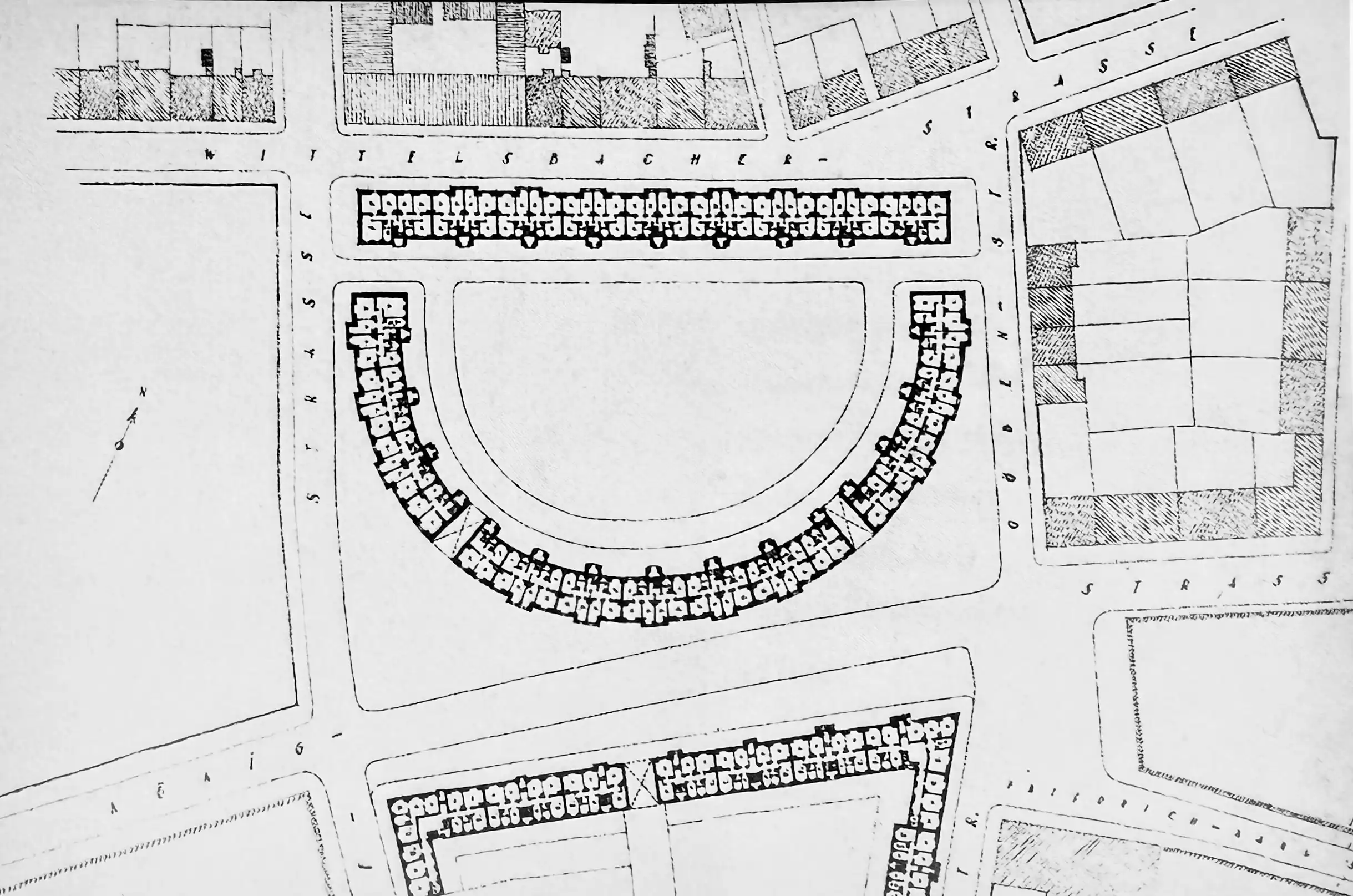

Königstraße 84-96, 97-109; Albert-Schweitzer-Straße 47-63; Goebenstraße 1-7; Pfaffstraße 24-30; Roonstraße 15, 17; Kaiserslautern, Germany

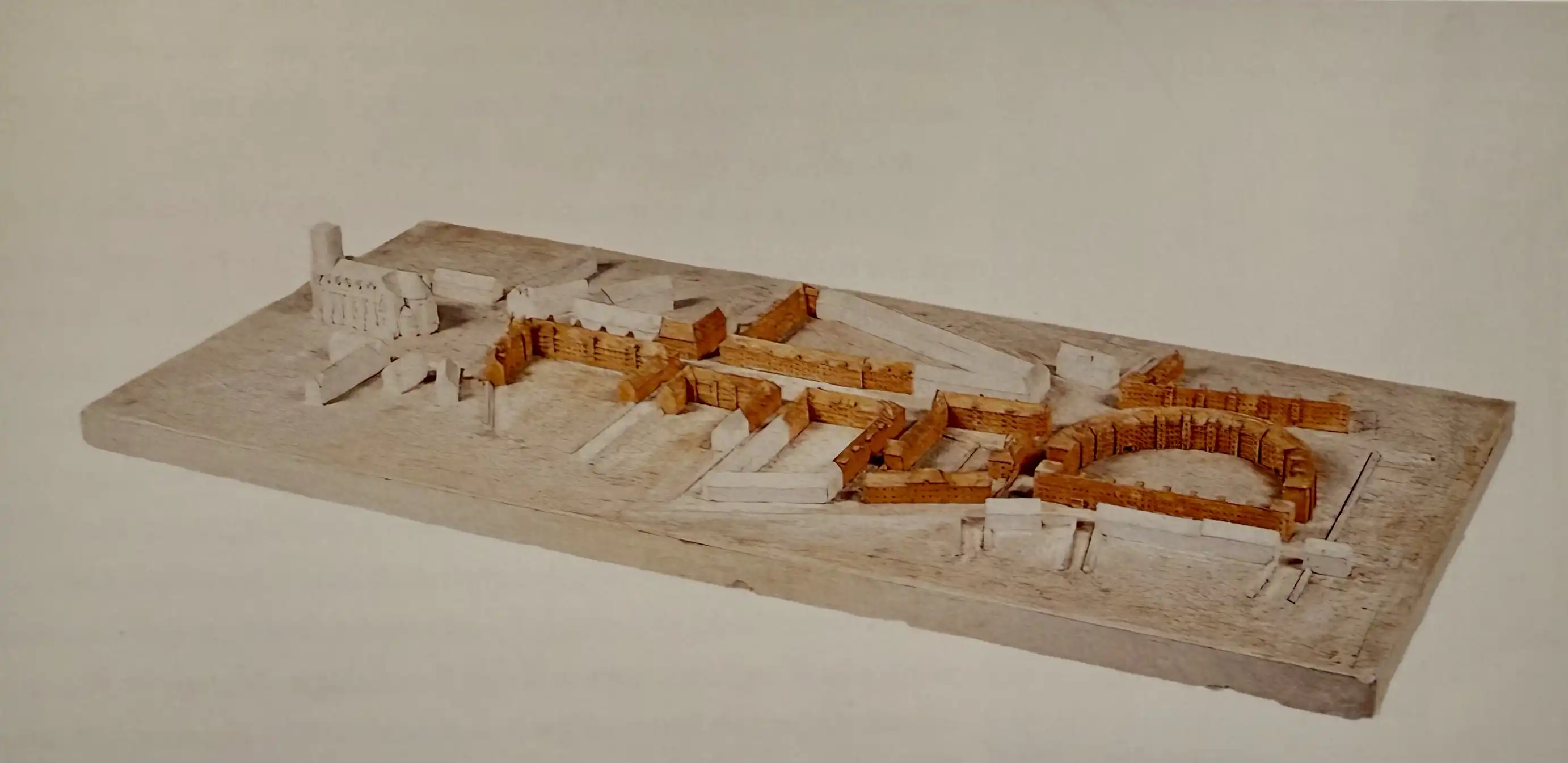

The Gemeinnützigen Baugesellschaft Kaiserslautern (Kaiserslautern Non-Profit Building Society’s) listed housing estate was built in the New Objectivity style according to plans by Hermann Hussong between 1926 and 1928.

The buildings are elongated, two- to four-story structures with flat or pent roofs. They are grouped around a green inner courtyard with a water basin.

Hermann Hussong

Hussong was born on September 20, 1881, in Blieskastel, Saarland. From 1900 to 1905, he studied architecture at the Technical University of Munich.

From 1905 to 1908, he worked as a trainee lawyer for the city of Homburg/Saar, where he was involved in the construction of a new sanatorium and nursing home.

Three years later, he was appointed to the Bamberg Regional Building Authority, where he oversaw the construction of new buildings for the State Basket Weaving Factory in Lichtenfels and two canons’ houses.

Kaiserslautern

He was appointed to Kaiserslautern on July 1, 1909, where he was responsible for urban planning and construction at the city planning office.

During his tenure, the deaconess house on Friedrich-Karl-Straße and the Zschokke factory building on Mainzer Straße were built in 1911. Hussong revised the city of Kaiserslautern’s expansion plan, which had been drawn up by Eugen Bindewald in 1887; it no longer met contemporary urban planning requirements.

After Bindewald retired in mid-1912, Hussong was solely responsible for planning a forest cemetery in Kaiserslautern.

During World War I, Hussong began planning a large housing construction program in Kaiserslautern. In April 1919, two nonprofit building associations were founded for this purpose.

Senior Building Officer

In 1920, Hussong was appointed City Planning Officer, making him the head of the City Planning Office. On November 26 of that year, he was promoted to Senior Building Officer. On March 10, 1921, he was elected to the City Council.

As city planning officer, he played an instrumental role in the construction of extensive residential complexes by nonprofit housing associations.

The residential complexes on Fischerstraße were built between 1919 and 1925, followed by the buildings in the Bunte Viertel (Colorful Quarter), located between Königstraße and Marienplatz, which were built from 1924 to 1925. The buildings on the exhibition grounds on Entersweilerstraße were built in 1925. From 1926 to 1928, the round building between Königstraße and Wittelsbacherstraße was constructed.

In 1926, he and architect Alois Loch planned the Graviusheim on Friedrich-Karl-Straße. From 1927 to 1928, the Grüner Block on Altenwoogstraße was constructed based on his designs. From 1927 to 1929, the Gelterswoog lido was constructed based on his designs. In 1929, he designed the new building for the Höhere Weibliche Bildungsanstalt (Higher Education Institution for Women) on Burgstraße, as well as the Protestant Vereinshaus (clubhouse) on Fackelrondell, once again collaborating with Alois Loch.

In 1931, Hussong was appointed Chief Building Director.

1933

On September 12 of that year, he was forced into retirement by the National Socialists under the “Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service”.

That same year, he moved to Zweibrücken, then to Heidelberg in 1934. In 1943, as part of the reemployment of retired civil servants, he was appointed head of local emergency measures in Kaiserslautern, where he oversaw the construction of air-raid shelters and the repair of war damage.

Heidelberg

From 1945 on, he served as chief building director, overseeing the technical departments of the Heidelberg city administration. Initially, his work consisted of repairing war damage. Several bridges that shaped the cityscape were restored or rebuilt under his responsibility, including the Old Bridge (1947), the Friedrichsbrücke (1949), the Ernst-Walz-Brücke (1950), and the newly designed main railway station (starting in 1950).

Until his retirement in 1952, he devoted himself to urban planning and restructuring housing and public buildings.

He died on September 16, 1960, in Heidelberg.

Throughout his life, Hussong was a member of the German Werkbund.

Kaiserslautern Non-Profit Building Cooperative

The Gemeinnützige Baugenossenschaft zur Errichtung von Kleinwohnungen eGmbH (Non-Profit Building Cooperative for the Construction of Small Apartments) and the Gemeinnützige Bauverein e.V. (Non-Profit Building Association) were founded in April 1919 to build new residential complexes. Two years later, the two associations merged to form the Gemeinnützige Bau-Aktiengesellschaft (Non-Profit Building Corporation).

Thanks to the close collaboration of Eugen Rhein (head of the Gemeinnützige Bau-AG), Mayor Franz Xaver Baumann, and City Planning Officer Hermann Hussong, Kaiserslautern still has a number of high-quality buildings from the 1920s that continue to shape the city’s image today.

Rundbau (Round Building)

The apartment building earned its name during construction because of its basket-arch-shaped floor plan.

A row of buildings encloses the large courtyard on the open side of the arch. Four residential paths connect this courtyard to the surrounding streets. The front sides of the buildings are accentuated by four- and five-story, flat-roofed elements. The pitched roof slopes toward the courtyard and is not visible from the outside.

In the center of the complex, there is a green inner courtyard with a water basin.

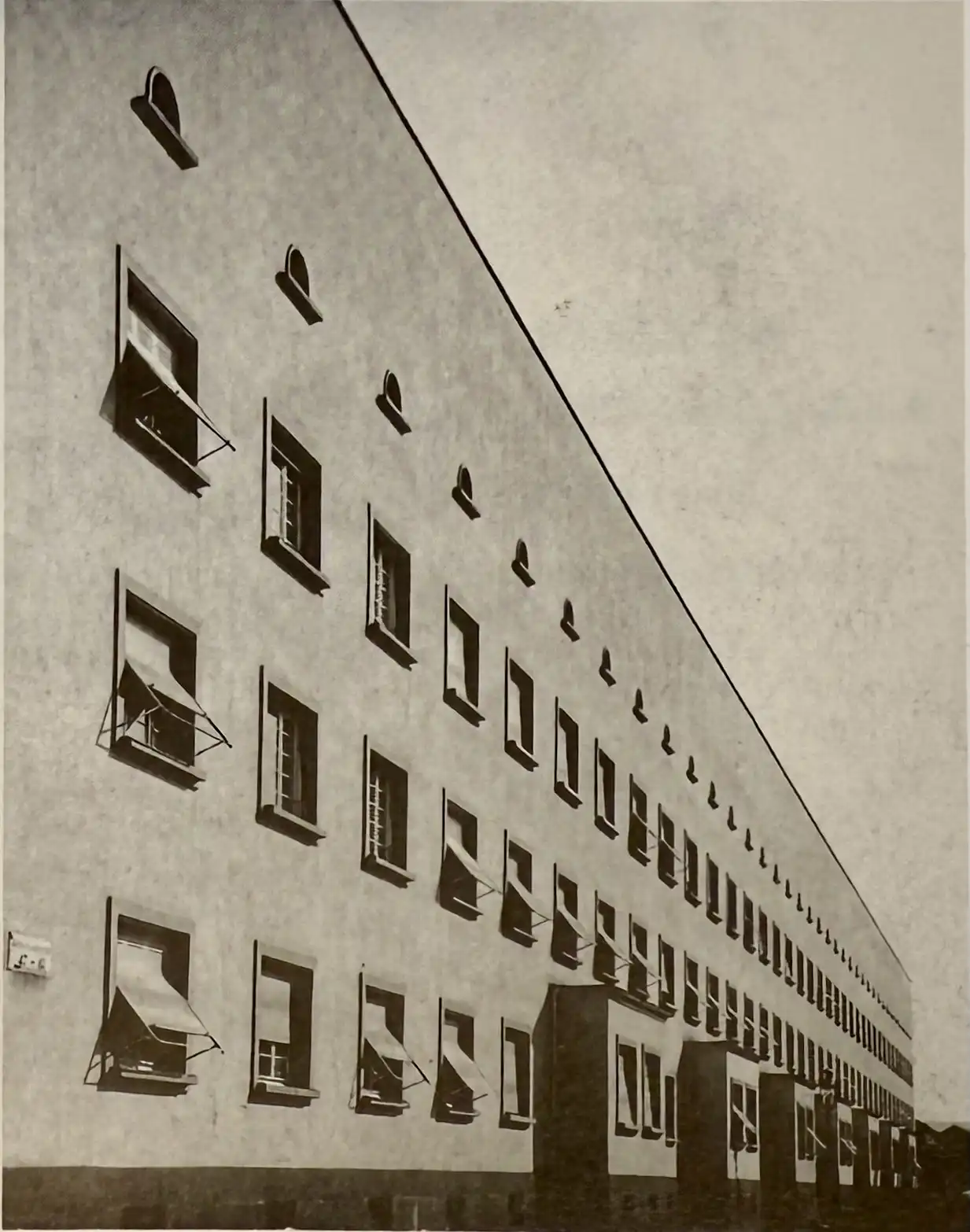

The buildings’ effect on the cityscape is based on their mass and grouping. The facades are structured by evenly spaced rows of windows and projections, as well as a row of small window openings under the roof that reflect the floor plan’s shape.

Rundbau, 1926-1928. Architect: Hermann Hussong

Rundbau, 1926-1928. Architect: Hermann Hussong

Design

A wide frame of dark sandstone surrounds the windows. Any architectural ornamentation has been avoided.

Rundbau, 1926-1928. Architect: Hermann Hussong. Photo: Daniela Christmann

The buildings exude practicality and tranquility. The unity of the complex is further emphasized by the pent roof that slopes toward the courtyard.

All entrances to the hallways, apartments, and basements are on the courtyard side. The special quality of living here only becomes apparent once you enter the courtyard. Hussong designed the green, semicircular courtyard with playgrounds and a large water basin to serve as a neutral, communal area for tenants.

The building’s original lemon-yellow paint caused quite a stir among tenants and the city population because it was considered too modern and garish.

Rundbau, 1926-1928. Architect: Hermann Hussong. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Rundbau, 1926-1928. Architect: Hermann Hussong. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Rundbau, 1926-1928. Architect: Hermann Hussong. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Rundbau, 1926-1928. Architect: Hermann Hussong. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Rundbau, 1926-1928. Architect: Hermann Hussong. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Mentors

The Horseshoe Estate in Berlin-Britz, designed by Bruno Taut and Martin Wagner in 1925, served as a model for the floor plan. Its core structure is laid out in a horseshoe shape around a body of water.

Taut commented on the design concept of the Horseshoe Estate: “What appeals to the senses in such developments is not the formation of squares and square walls or baroque lines, but rather the moment of movement and transition between rows and groups when such a development is successful. Certainly, in this view, streets are framed by house walls, but there is no focal point.” (Bruno Taut: Neue und alte Form im Bebauungsplan [New and Old Forms in the Development Plan]. In: Wohnungswirtschaft, 3(2026), pp. 198f.)

Other comparable buildings from this period include the Hamm-Marsch residential complex near Hamburg, built between 1928 and 1930 according to Heinrich Schöttler’s plans under Fritz Schumacher‘s supervision, and the Rundling settlement in Lößnig near Leipzig, completed in 1930 by Hubert Ritter.

This form ultimately stems from the “King’s Circus” and “Royal Crescent” residential complexes designed by John Wood the Elder and John Wood the Younger in Bath in the 18th century.

Apartments

The circular building has 164 apartments spread over four floors. The floor-to-ceiling height is 2.91 meters, and the clear room height is 2.73 meters.

All apartments are the same size. Each apartment has 53 square meters of floor space and comprises two rooms, a kitchen, a bathroom, and a toilet. Each apartment has a lockable storage room and access to the basement storage area.

Tenants have access to a laundry room and a drying room in the basement on a rotating basis. Eight apartments also have an additional 17-square-meter heated room on the third floor. At the time of completion, apartments with this additional room cost between 540 and 612 Reichsmarks per year, whereas apartments without this room were rented for 396 Reichsmarks per year.

Good amenities at affordable rents

The construction company intended to use the circular building to provide as many small-floor-area apartments as possible with good amenities and affordable rents.

During the planning stage, all furnishing options were considered to make optimum use of the available space. Each apartment had to have room for at least five beds.

Two apartments shared access to the stairwell on each floor. The plans included the possibility of removing the stairwell wall at a later date to combine two apartments. All apartments had the same floor plan and furnishings, which significantly reduced costs.

To enable mass production, only two different window sizes and door formats were used on each floor.

Despite limited resources, Hermann Hussong prioritized quality of living. Thermally insulated walls, solid ceilings, and fireproof stone staircases were standard for him.

The large, three-part windows with shutters were designed to provide pleasant lighting conditions. The architect paid attention to distinctly functional forms for construction details such as the stove, as recommended by the German Werkbund.

Criticism

The round building was heavily criticized by the homeowners’ association due to its high-quality furnishings and comparatively low rent, as it represented significant competition for their interests. In their publication, the Bürger- und Hausbesitzerzeitung (Citizens’ and Homeowners’ Newspaper), they mockingly referred to the building as a “Bug Palace.”

Hermann Hussong: Urban Planner and Architect

Hussong described himself first and foremost as an urban planner, then as an architect and artist.

His urban planning skills were praised in contemporary reviews:

“Hussong loves designing buildings in three dimensions. He handles space with confidence and generosity, grading it in depth, layering it in height, and expanding it in width.” He needs a lot of space, but he also creates a lot of space, such as large forecourts from which the complexes grow to their full potential.” He also excels at designing the relationship between the surroundings and the core of the building.” He captures the radiance of the streets, creates spaces for lingering within the rhythm of the design, and permeates and shapes the city in broad strokes. He leaves nothing to chance but rather seeks to translate the movement of the city into a dynamic architectural image according to meaningful and appropriate laws.” (Wilhelm Westecker: Modern Architecture in the Palatinate. In: Kurpfälzer Jahrbuch 1928, Heidelberg, 1928, p. 166).

With a keen sense of scale and proportion, he created an urban framework through the arrangement of his buildings, which defines space and contributes to the lasting enhancement of the urban environment. Through his consistent application of symmetry in floor plans and elevations, he achieved an increased intensity. The effect was austere and functional yet clear and manageable.

New Objectivity

Hussong applied the design principles of the style particularly consistently in the Rundbau. Each apartment had a functional floor plan with sufficient lighting and ventilation on two sides. Social hygiene was always a major concern of his, and he was now able to incorporate it into social housing construction. Another aspect of social reform is the color concept. Hussong developed it for both the façade and the interiors.

Post-war period

By 1950, the war-damaged buildings had been repaired. In 1975, new windows and doors were installed, altering the complex’s overall character.

By the end of the 1970s, the simple water basin in the inner courtyard had been converted into a fountain. On June 26, 1989, Fritz Korter‘s sculpture Die zwei Schwestern (The Two Sisters) was added to the complex.

Originally, the sculptor created it as a fountain sculpture for Villa Stähler at Rittersberg 13 in Kaiserslautern. After the villa was demolished in 1989 to make way for the new theater, the artificial stone sculpture was placed on the edge of the basin inside the complex.

Rundbau, 1926-1928. Architect: Hermann Hussong. Photo: Daniela Christmann

A comprehensive restoration of the buildings, including redesigning the apartments and renovating the residential area, was completed in 2005.

The complex has been a listed building since 1986 and is considered an outstanding example of New Objectivity architecture in terms of urban planning and design.