Planning: 1919-1921; Construction: 1922-1924

Architect: Hermann Hussong

Fischerstraße 16-28, 15-37; Friedrichstraße 13-19; Wilhelmstraße 2-6; Bismarckstraße 27, 29, 31, 37c; Kanalstraße 34-46, Kaiserslautern, Germany

The residential buildings on Fischerstraße in Kaiserslautern were completed between 1922 and 1924. The German Reich commissioned them at the request of the French occupying power based on designs by Hermann Hussong, Kaiserslautern’s town planning officer. Hussong’s planning for the project began in 1919, after the conclusion of World War I.

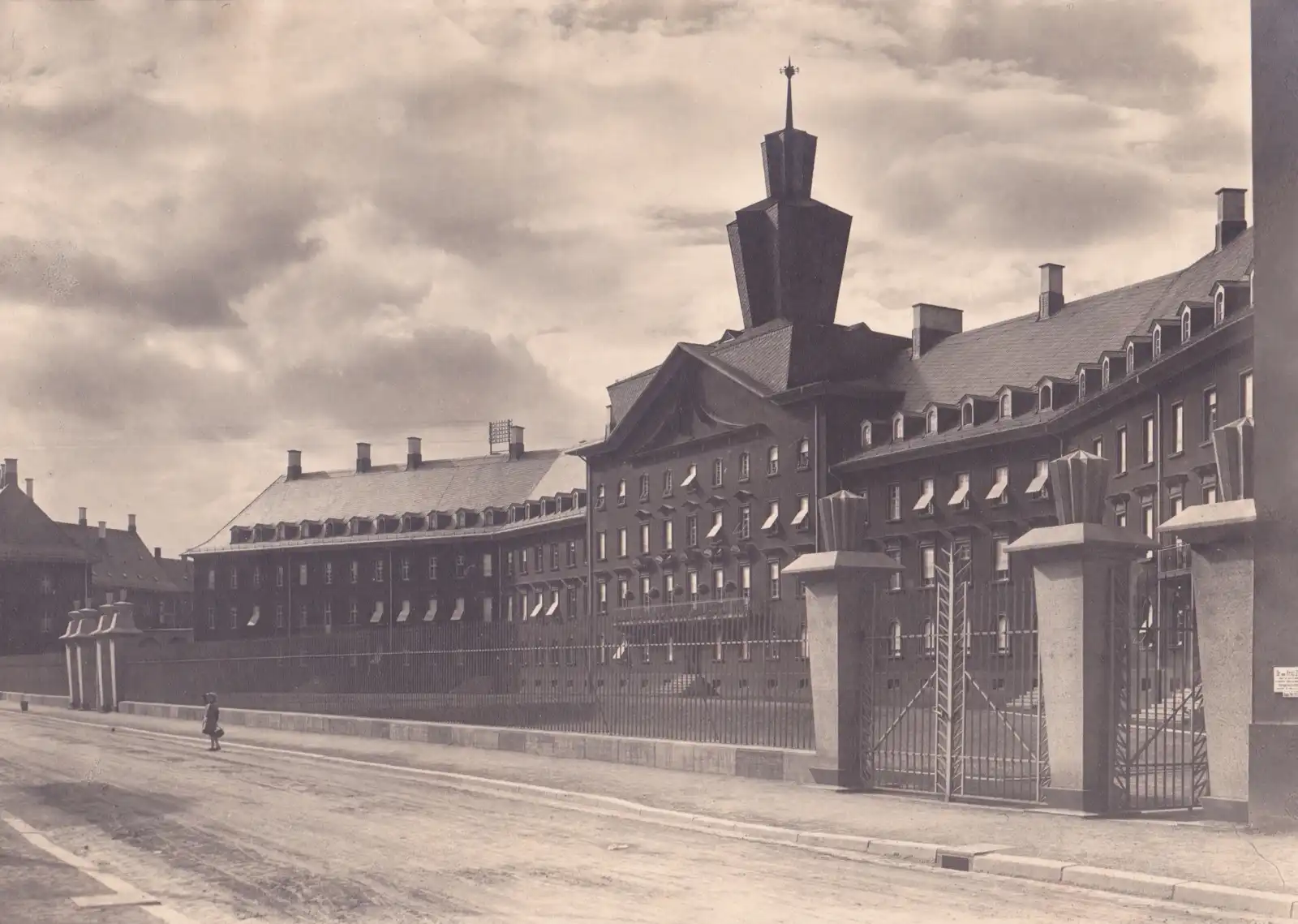

Fischerstrasse Housing Estate, 1925. Photo: Reinhold Wilking

Fischerstraße Housing Complex, 1922-1924. Architect: Hermann Hussong. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Hermann Hussong

Hermann Hussong was born on September 20, 1881, in Blieskastel, Saarland. From 1900 to 1905, he studied architecture at the Technical University of Munich.

From 1905 to 1908, he worked as a trainee teacher for the city of Homburg/Saar‘s district administration and was involved in the construction of a new sanatorium and nursing home.

Three years later, he was appointed to the Bamberg Land Construction Office, where he oversaw the construction of a state basket-weaving factory in Lichtenfels and two canons’ houses.

Hermann Hussong. Photo: Tille Berger-Haake

Kaiserslautern

On July 1, 1909, Hussong was appointed to the city planning office in Kaiserslautern, where he was responsible for urban planning and construction.

During his time in office, the deaconess house on Friedrich-Karl-Straße and the Zschokkewerke factory building on Mainzer Straße were built in 1911. Hussong revised the city of Kaiserslautern’s expansion plan, which had been drawn up by Eugen Bindewald in 1887, as it no longer met contemporary urban planning requirements.

After Bindewald retired in mid-1912, planning the Waldfriedhof (forest cemetery) in Kaiserslautern became Hussong’s first solo project.

During World War I, Hussong began planning a major housing construction program in Kaiserslautern. For this purpose two nonprofit building associations were founded in April 1919.

City Planning Director

In 1920, Hussong was appointed city planning officer, thus becoming head of the city building department. On November 26 of that year, he was promoted to senior building officer, and on March 10, 1921, he was elected to the city council.

As city planning officer, he played an instrumental role in the construction of extensive housing estates by non-profit housing associations.

From 1919 to 1925, the Fischerstrasse housing estates were completed. From 1924 to 1925, the residential buildings of the Colored Quarter, located between Königstrasse and Marienplatz, were finished. In 1925, construction was completed on the exhibition grounds on Entersweilerstrasse. From 1926 to 1928, the Rundbau residential buildings were constructed between Königstrasse and Wittelsbacherstrasse.

In 1926, he and architect Alois Loch planned the Graviusheim on Friedrich-Karl-Straße. From 1927 to 1928, the Green Block on Altenwoogstrasse was constructed based on Hussong’s designs. From 1927 to 1929, the Gelterswoog lido was constructed based on his designs. In 1929, he designed the new building for the Höhere Weibliche Bildungsanstalt on Burgstrasse, as well as the Protestant clubhouse on Fackelrondell, once again collaborating with Alois Loch.

In 1931, Hussong was appointed senior building director.

1933

On September 12, 1933, the National Socialists forcibly retired him as part of the “Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service.”

That same year, he moved to Zweibrücken, followed by Heidelberg in 1934. In 1943, he was appointed head of local emergency measures in Kaiserslautern, one of many retired civil servants reassigned to manage the construction of air raid shelters and the repair of war damage.

Heidelberg

Beginning in 1945, he managed the technical tasks of the Heidelberg city administration as senior building director. Initially, his work consisted of repairing war damage. Several bridges that shaped the cityscape were restored or rebuilt under his responsibility, including the Old Bridge (1947), the Friedrich Bridge (1949), the Ernst Walz Bridge (1950), and the redesign of the main railway station (starting in 1950).

Until his retirement in 1952, Hussong devoted himself to urban planning and restructuring housing and public buildings.

He died in Heidelberg on September 16, 1960.

Hussong was a member of the Deutscher Werkbund.

Historical Background

In 1918, the Prussian Parliament made the right of every citizen to a healthy home within their financial means a law of the Weimar Constitution.

The Prussian Housing Act of March 28, 1918, authorized the enactment of building codes to ensure healthy living with adequate lighting and ventilation in the interest of housing welfare.

State measures such as rent control, the provision of public land for the construction of new housing, state housing loans, and the subsidization of building societies are examples of an unprecedented involvement of the state and local authorities in the creation of housing.

At the same time, the Treaty of Versailles obligated the German Reich to provide sufficient housing for the French occupying forces.

Because of the existing housing shortage, it was decided to build a new residential complex for French officers and their families in Fischerstrasse at the expense of the German Reich, beginning in 1921, in addition to the existing apartments.

Fischerstrasse Housing Estate, 1925. Photo: Reinhold Wilking

Fischerstrasse Housing Estate, 1925. Photo: Reinhold Wilking

Housing Cooperatives

In 1919, two building societies were founded in Kaiserslautern: the “Gemeinnützige Baugenossenschaft zur Errichtung von Kleinwohnungen e.G.m.b.H.” for those with compulsory insurance and the “Gemeinnützige Bauverein e.V.” for those without compulsory insurance. In 1921, the associations merged into a non-profit corporation with a share capital of 1.8 million marks.

One-quarter of the capital was contributed by the members of the former Bauvereine and three-quarters by the city. Their financial participation gave the city a say and required close cooperation with the municipal building department.

Housing in Kaiserslautern

After the end of the First World War, all the conditions were in place for extensive housing construction. On Hussong’s advice, the city of Kaiserslautern had pursued a successful policy of land accumulation and had taken timely action against land speculation.

The funds approved by Speyer, Munich and Berlin for occupation buildings and the development and implementation plans prepared by Hussong during the war were available.

Hussong, who had taken over as head of the municipal building department in 1920, was instrumental in planning the housing estates of the “Gemeinnützige Baugesellschaft AG”.

Fischerstrasse

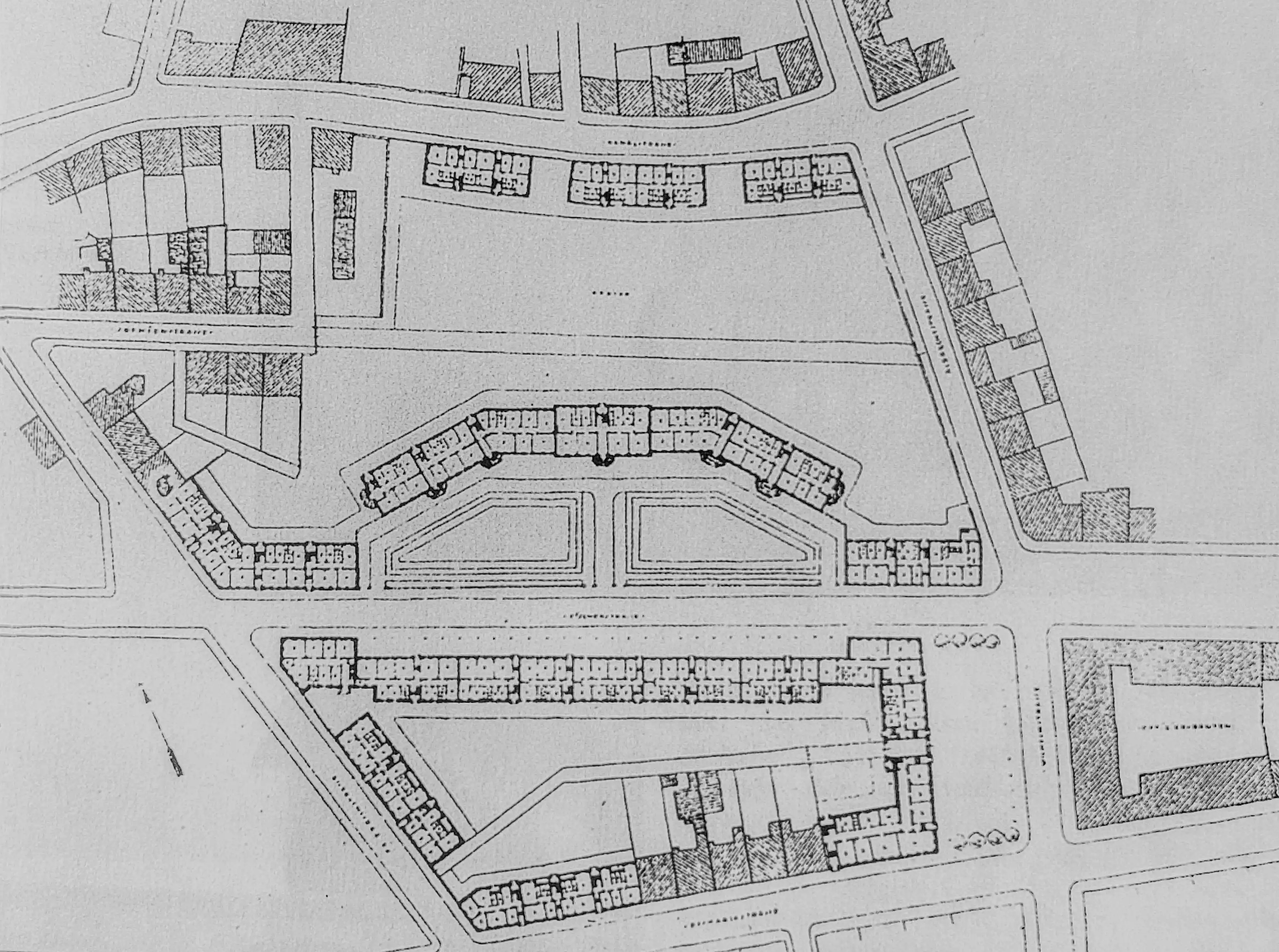

At the request of the French Occupation, planning began in 1919-1920 for a large housing development on Fischerstraße, Albrechtstraße, and Bismarckstraße. The Imperial Government initially granted the City of Kaiserslautern funds for the construction of 24 officers’ apartments, which soon grew to a total of 144 apartments.

Property

The search for a suitable plot of land proved to be lengthy. The city administration finally offered the Reich a large area east of the synagogue, which extended on both sides of Fischerstrasse.

Since this was a swampy and spring-fed area, Hussong used the then-advanced method of laying the foundations on reinforced concrete piles. The relatively low price of the land justified this costly technique.

Construction during the inflationary period

Despite a shortage of materials, the first construction phases were carried out during the inflationary period. In 1923, however, the German government was unable to finish the work due to currency stabilization. Fortunately, the city of Kaiserslautern took over and finished the work that had been started.

Design

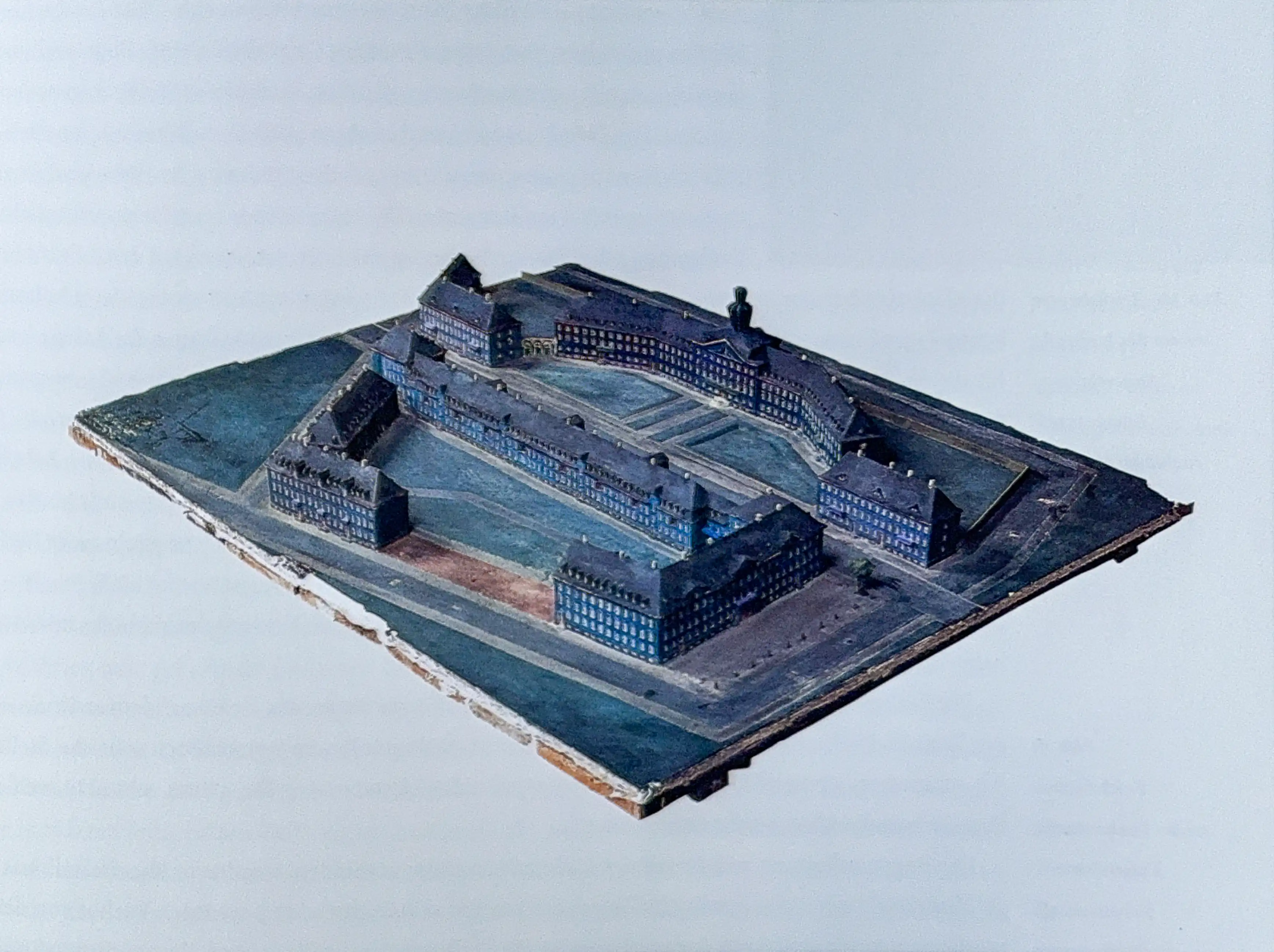

Hermann Hussong designed a representative, axially symmetrical complex with a high hipped roof and a series of dormer windows.

To the north of Fischerstrasse, a three-story development with a four-story central wing and large apartments for officers’ families was built.

The dominant central wing was intended for the commandant’s office and the garrison telephone exchange.

Three-story wings extend from the nine-axis, four-story central building. These wings bend diagonally forward after six axes, and each has a further twelve axes.

Polygonal stair ramps lead to the mezzanine floor and the five entrances.

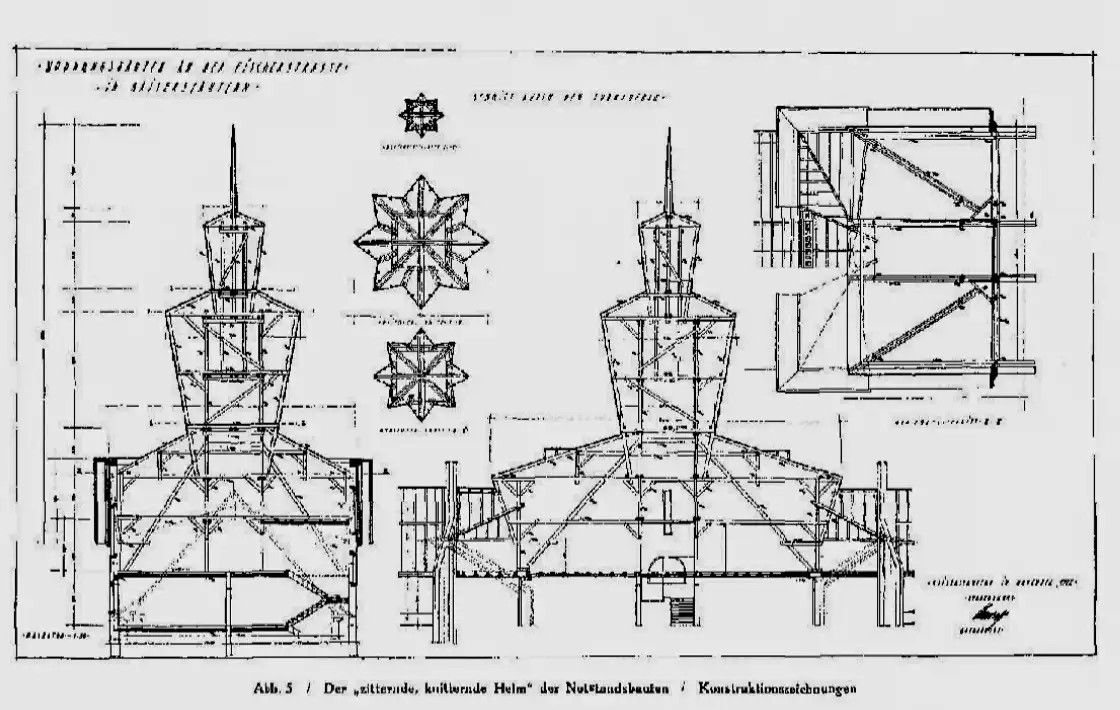

A trapezoidal forecourt separates the northern residential block from the street. The central section is adorned with a large triangular gable and a star-shaped ridge turret that is almost 24 meters high.

Fischerstrasse Housing Estate, 1925. Photo: Reinhold Wilking

Fischerstraße Housing Complex, 1922-1924. Architect: Hermann Hussong. Construction Drawings

Fischerstraße Housing Complex, 1922-1924. Architect: Hermann Hussong. Floorplan

Residential Buildings Fischerstraße. Original plaster model, painted in color. Photo: Gunther Balzer

Residential Buildings Fischerstraße. Contemporary photograph

Windows and Roofs

The wing buildings have gabled roofs with dormers that end in hipped roofs at the outer ends.

The windows on the lowest full story have round arches and horizontal roofs above the openings on the second floor.

Fischerstraße Housing Complex, 1922-1924. Architect: Hermann Hussong. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Fischerstraße Housing Complex, 1922-1924. Architect: Hermann Hussong. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Fischerstraße Housing Complex, 1922-1924. Architect: Hermann Hussong. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Apartments Furnishing

Although kitchen balconies, guest rooms, and luggage compartments were not planned for the standard apartments financed from Reich funds, Hussong complied with the demands of the French occupying power for the apartments to be furnished to a higher standard.

The apartments on the south side of Fischerstrasse were intended for non-commissioned officers. These apartments were located in a two-story central section adjoined by three-story wings.

Color Schemes

Hussong placed great importance on the color schemes of the facades and interiors, taking regional traditions into account and following the examples and suggestions of contemporary colleagues such as Bruno Taut.

The façades of the southern group of houses and the buildings flanking them to the north have a steel-green tone. The house stones of the door and window frames are bluish-purple. The main cornice and all the wood are white. The main building to the north has deep blue plastered surfaces and bluish-green house stones, and the wood is white again. The green lawn in the recessed fields of the forecourt and the light tone of the fencing complement the color scheme.” (Building description by Hermann Hussong)

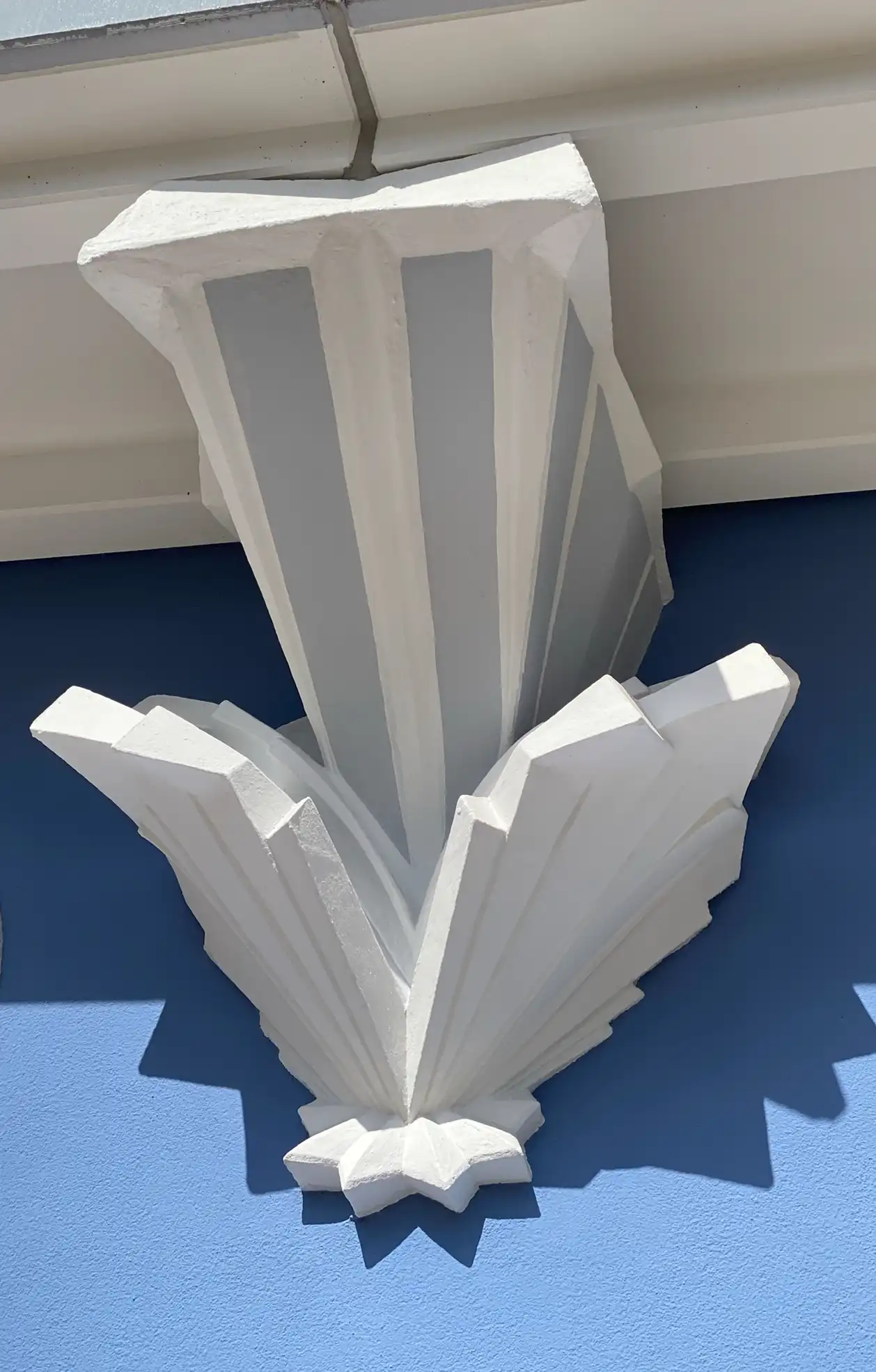

Details

The structural details were just as important to Hussong as the color scheme. Based on his designs, students at the Kaiserslautern Craftsmen’s School produced balcony brackets, doors, banisters, stucco decorations, and grilles. The elaborate balcony brackets, in particular, exhibit clear Expressionist influences in their design.

Fischerstraße Housing Complex, 1922-1924. Architect: Hermann Hussong. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Fischerstraße Housing Complex, 1922-1924. Architect: Hermann Hussong. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Fischerstraße Housing Complex, 1922-1924. Architect: Hermann Hussong. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Fischerstraße Housing Complex, 1922-1924. Architect: Hermann Hussong. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Fischerstraße Housing Complex, 1922-1924. Architect: Hermann Hussong. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Criticism

The buildings on Fischerstrasse were heavily criticized in the contemporary trade press for their elaborate detailing. This overlooked the fact that the buildings were originally representative structures for the French occupying forces, not simple residential buildings.

The tower structure and elaborate balcony brackets were particularly provocative. The complex’s design and execution cannot be compared with the 1920s’ residential buildings, which were designed to maximize living space with minimal resources.

Due to the completely different conditions during the planning phase, the Fischerstrasse buildings did not meet the rational housing construction requirements of the time.

However, Hussong demonstrated his understanding of this concept in his later buildings, including the Rundbau, located near the former Pfaff sewing machine factory in Kaiserslautern.

During the National Socialist Era

In 1936, the bars and pillars of the forecourt were demolished. Due to a widening of the street, the corner pavilions of the buildings at Fischerstraße 16-28 were opened up by arcades on the first floor in 1938.

In 1939, the ridge turret, popularly known as the “Maggiflasche” or “umbrella stand,” was demolished as so called “kulturbolschewistisch” and “not fitting into the street scene.”

Today’s Condition

After the war, the interior was renovated, and the building was repaired from war damage.

The residential complex has been a listed building since July 8, 1994. In 1995, the northern building’s façade was significantly altered by installing a new entrance.

Fischerstraße Housing Complex, 1922-1924. Architect: Hermann Hussong. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Fischerstraße Housing Complex, 1922-1924. Architect: Hermann Hussong. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Fischerstraße Housing Complex, 1922-1924. Architect: Hermann Hussong. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Further Reading

Architekt Hermann Hussong. In: Daniela Christmann, Die Moderne in der Pfalz. Künstlerische Beiträge, Künstlervereinigungen und Kunstförderung in den zwanziger Jahren. Heidelberg 1999, S. 98-117.

Präger, Christmut: Barock, expressiv und modern. Architektur von 1919 bis 1930. In: Es kommt eine neue Zeit! Kunst und Architektur der zwanziger Jahre in der Pfalz. Köln 1999, S. 210-223.

Daniela Christmann: Vom Pathos zur Sachlichkeit. Hermann Hussong – Fischerstraße und Rundbau in Kaiserslautern. Zwei Beispiele für den Wohnungsbau der zwanziger Jahre in Deutschland. In: RückSicht. Festschrift für Hans-Jürgen Imiela. Mainz 1997, S. 199-212.

Wohnanlagen Fischerstraße, 1922-1924. Architekt: Hermann Hussong. Foto: Daniela Christmann

Wohnanlagen Fischerstraße, 1922-1924. Architekt: Hermann Hussong. Foto: Daniela Christmann