Villa Bechtolsheim, 1897-1898. Architect: Martin Dülfer. Photo: Daniela Christmann

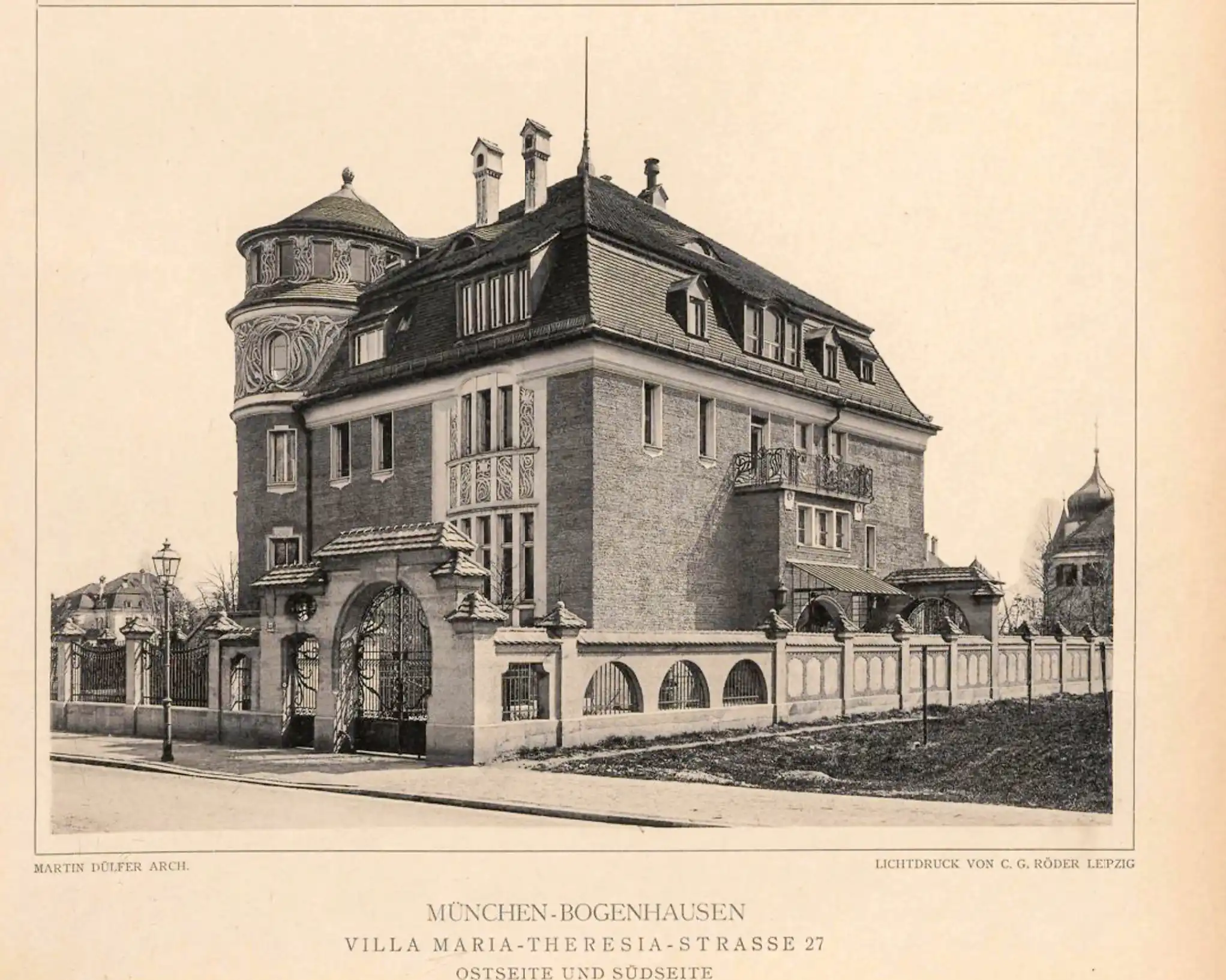

Villa Bechtolsheim, 1897-1898. Architect: Martin Dülfer. Contemporary image

Villa Bechtolsheim, 1897-1898. Architect: Martin Dülfer. Contemporary image

Villa Bechtolsheim, 1897-1898. Architect: Martin Dülfer. Contemporary image

Villa Bechtolsheim, 1897-1898. Architect: Martin Dülfer. Photo: Daniela Christmann

1897 – 1898

Architect: Martin Dülfer

Maria-Theresia-Strasse 27, Munich-Bogenhausen, Germany

The villa designed by Martin Dülfer for Baron Clemens von Bechtolsheim in Munich-Bogenhausen is probably the oldest surviving Art Nouveau building in Germany.

The Engineer Clemens von Bechtolsheim

Born in Munich in 1852, Clemens von Bechtolsheim was a German engineer and entrepreneur.

As early as 1867, his initial ideas and developments attracted the attention of the physicist Philipp von Jolly, who gave Bechtolsheim private tuition in preparation for studying mechanical engineering at the Polytechnic Institute in Munich. There Bechtolsheim met the mechanical engineer Carl von Linde. Together they worked on refrigeration and heat pumps. He soon became a close friend of Rudolf Diesel as well.

Recognizing the high energy consumption of traditional salt production in saltworks, Bechtolsheim developed the process of pre-drying using a centrifuge and post-drying on a rack.

He received 44 patents for his inventions. In 1886, he built the Alfa separator for milk centrifuges, which improved cream separation through the use of refined disk inserts in the separator drum and was immediately installed in all machines.

In 1889, Bechtolsheim married Therese Countess Fugger of Kirchberg and Weissenhorn in Augsburg. His inventions attracted more attention abroad than in his native Germany. Shortly after the wedding, he moved to Stockholm, where two of his three children were born.

He worked for the Alpha-Laval company in Stockholm. By 1902, some 275,000 Alfa centrifuges had been sold. In 1904, Bechtolsheim built his own factory, Alphawerke Gauting, to manufacture his separator.

The Architect Martin Dülfer

Dülfer graduated from the Technical University of Munich in 1886 and set up his own architectural office in Munich a year later. At first, he built buildings in the neo-baroque style of historicism, which was typical of the time and the region.

Around 1900, Dülfer turned to Art Nouveau. This resulted in commercial buildings and villas for the upper middle class – such as the commercial building of the publishing house of the Münchner Allgemeine Zeitung on Bayerstraße, which was completely modernized in 1929, or the Villa Bechtolsheim.

Villa Bechtolsheim

In 1895, Clemens von Bechtolsheim acquired a 3940-square-meter plot of land opposite the Maximiliansanlagen from the City of Munich.

The house at Maria-Theresia-Strasse 27, with its projecting oval tower and central heating, was built between August 1896 and April 1898.

The stucco decorations are by Richard Riemerschmid. Riemerschmid was inspired by the work of architect Louis Henry Sullivan, who added ornamental elements to his steel frame buildings.

Louis Henry Sullivan, Wainwright Building, Saint Louis, USA, 1890. Detail

Villa Bechtolsheim, 1897-1898. Architect: Martin Dülfer. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Villa Bechtolsheim, 1897-1898. Architect: Martin Dülfer. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Except for the perimeter walls of the basement, which are concrete masonry, the entire building is masonry, with sparse use of local stone, and has a tile roof.

The facades are finished with rough plaster. The floors are made of concrete between steel beams.

In the design of the building, which is detached on all four sides and whose main façade is separated from the street to the northwest by a 10-meter wide front garden, the architect visibly avoided any reference to historical styles in order to give the building a modern appearance.

This is particularly evident in the ornamentation of the tower frieze, which was freely applied in cement to the rough lime mortar base according to designs by Richard Riemerschmid of the Alfred Völker stucco company in Munich.

The metalwork and garden fences were made by the Grohmann metalworking company.

Villa Bechtolsheim, 1897-1898. Architect: Martin Dülfer. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Villa Bechtolsheim, 1897-1898. Architect: Martin Dülfer. Photo: Daniela Christmann

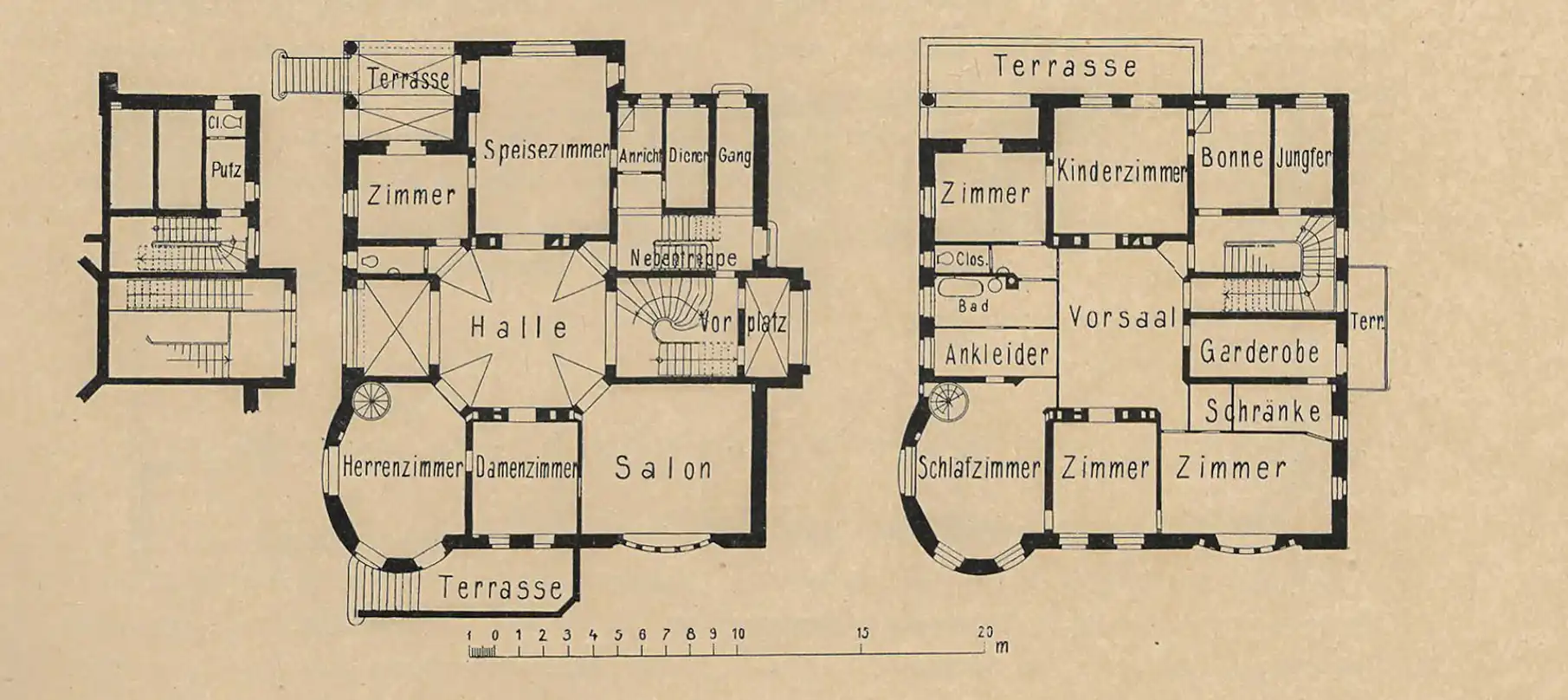

Floor plan and interiors

On the mezzanine floor, all the common rooms lead off from a central octagonal hall, the sloping corners of which are used as distribution rooms or entrances to the lounges. By moving two wide glass partitions, it was possible to connect the staircase with the hall and the conservatory, creating a generous suite of rooms about 15 meters long.

Villa Bechtolsheim, 1897-1898. Architect: Martin Dülfer. Floorplan

The bedrooms were on the upper floor and the servants’ rooms were in the attic. The tower room with its surrounding windows overlooked the Maximilian grounds and served as the master’s drawing studio. There was a lockable opening in the floor through which a small laid table could be pulled up.

The floral ornamentation of the Liberty style can be found in the wrought iron railings and the stucco work in the interior.

Villa Bechtolsheim, 1897-1898. Architect: Martin Dülfer. Contemporary image

Villa Bechtolsheim, 1897-1898. Architect: Martin Dülfer. Contemporary image

The restoration of the villa in 1970 was largely based on its original condition. Today the villa is a listed building.