1929 – 1930

Architect: Adolf Gustav Schneck

Hanner Steige 1, Bad Urach, Germany

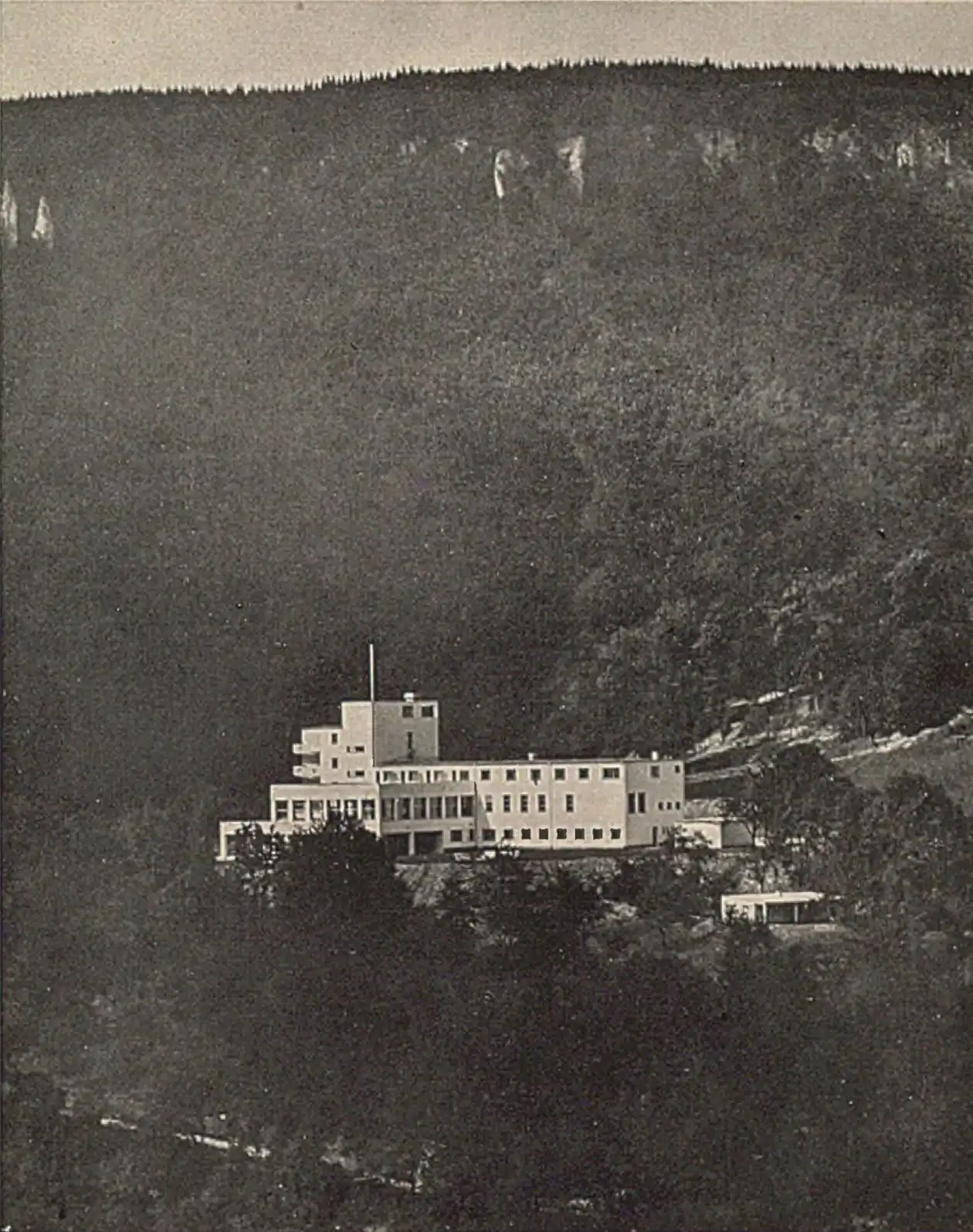

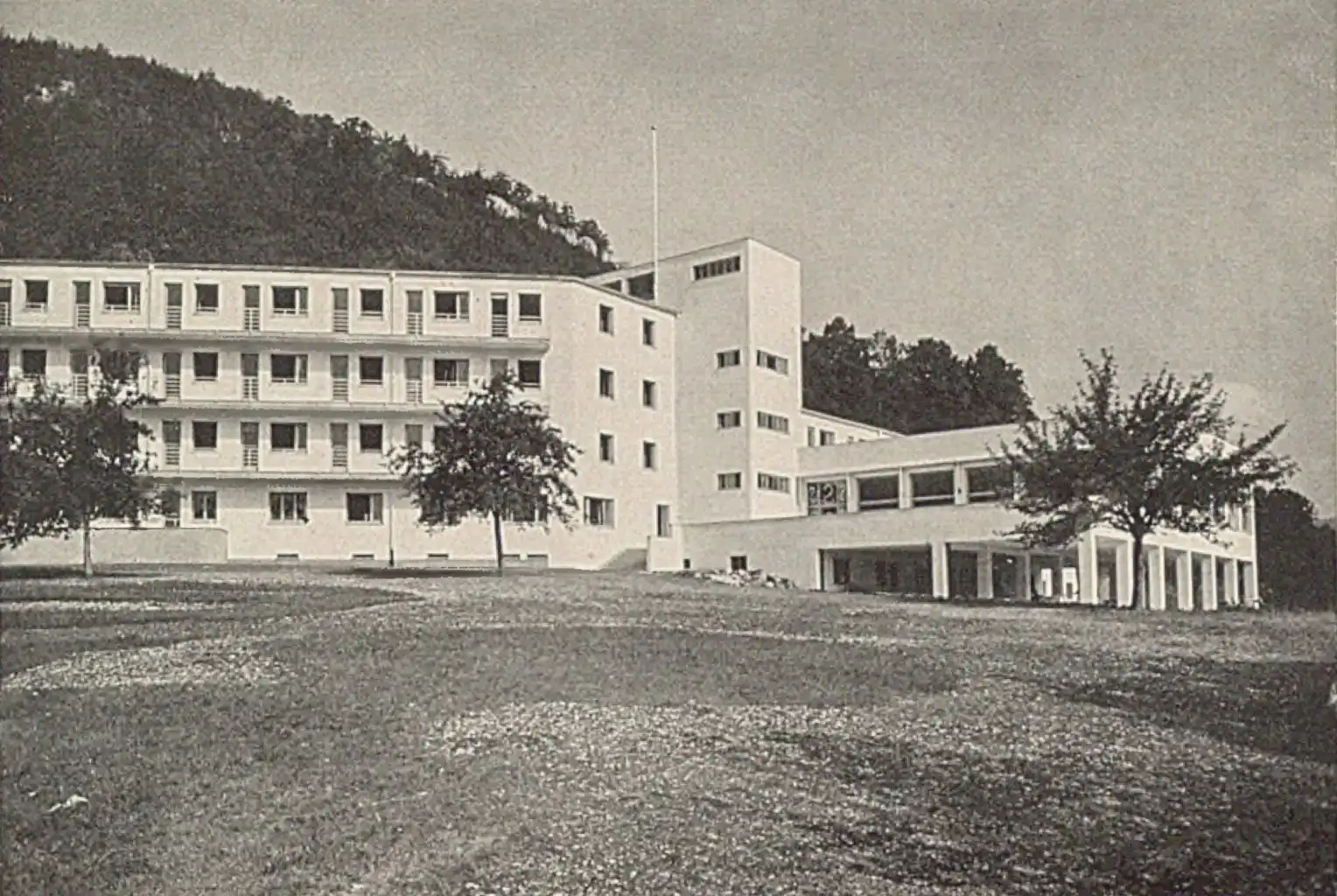

The Haus auf der Alb in Bad Urach, on the northern edge of the Swabian Alb, was built between 1929 and 1930 as a merchants’ retreat in the classical modernist style according to the plans of architect Adolf Gustav Schneck.

After a varied history of use, it has been a listed building since 1983 and has been used as a conference center for the Landeszentrale für politische Bildung Baden-Württemberg since 1992.

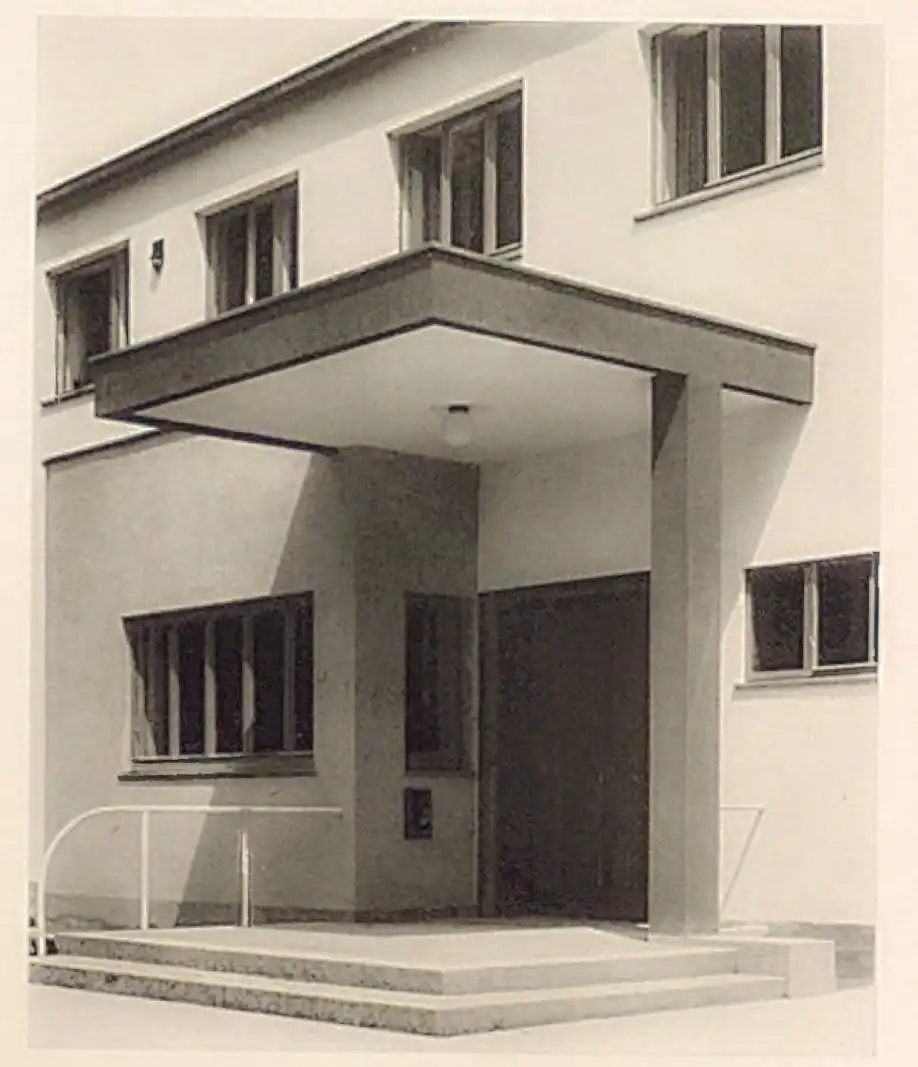

Haus auf der Alb, 1929-1930. Architect: Adolf Gustav Schneck. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Haus auf der Alb, 1929-1930. Architect: Adolf Gustav Schneck. Contemporary photography

Haus auf der Alb, 1929-1930. Architect: Adolf Gustav Schneck. Contemporary photography

Haus auf der Alb, 1929-1930. Architect: Adolf Gustav Schneck. Contemporary photography

Gustav Adolf Schneck

The son of a furniture maker, Schneck completed a three-year apprenticeship as a saddler and upholsterer in his parents’ business in Esslingen am Neckar in 1897. He then began his apprenticeship with a period of travel and attendance at the trade school in Basel.

After returning to Esslingen, he took over his parents’ business in 1907 and at the same time began studying at the Stuttgart School of Arts and Crafts under Bernhard Pankok, among others.

In 1912 he switched to architecture studies at the Technical University of Stuttgart, which he completed in 1918 with a thesis on the Stuttgart Central Station under Paul Bonatz.

His studies enabled him to become a freelance architect and furniture designer in 1919, and two years later he was offered a teaching position at the Stuttgart School of Arts and Crafts.

There he became head of the department for furniture construction and interior design in 1922 and professor in 1923.

Hellerau

One year later he curated the exhibition “Die Form [ohne Ornament]”. In 1926/1927 Schneck designed the standardized furniture program “Die billige Wohnung” for Karl Schmidt-Hellerau, which was produced with great success in the Deutsche Werkstätten Hellerau until the 1930s.

Weissenhof Estate

Schneck was the second Stuttgart architect, after Richard Döcker, to work on the Weissenhof Estate. In 1926/1927 Schneck designed and built two single-family houses: House 11 at Friedrich-Ebert-Straße 114, in which he lived, and House 12 at Bruckmannweg 1.

He also designed the interior of an apartment in the house of architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe.

Haus auf der Alb

The following year, he received another major commission that would further enhance his fame: he was commissioned by the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Kaufmannserholungsheime (DGK) to design the Haus auf der Alb near Bad Urach.

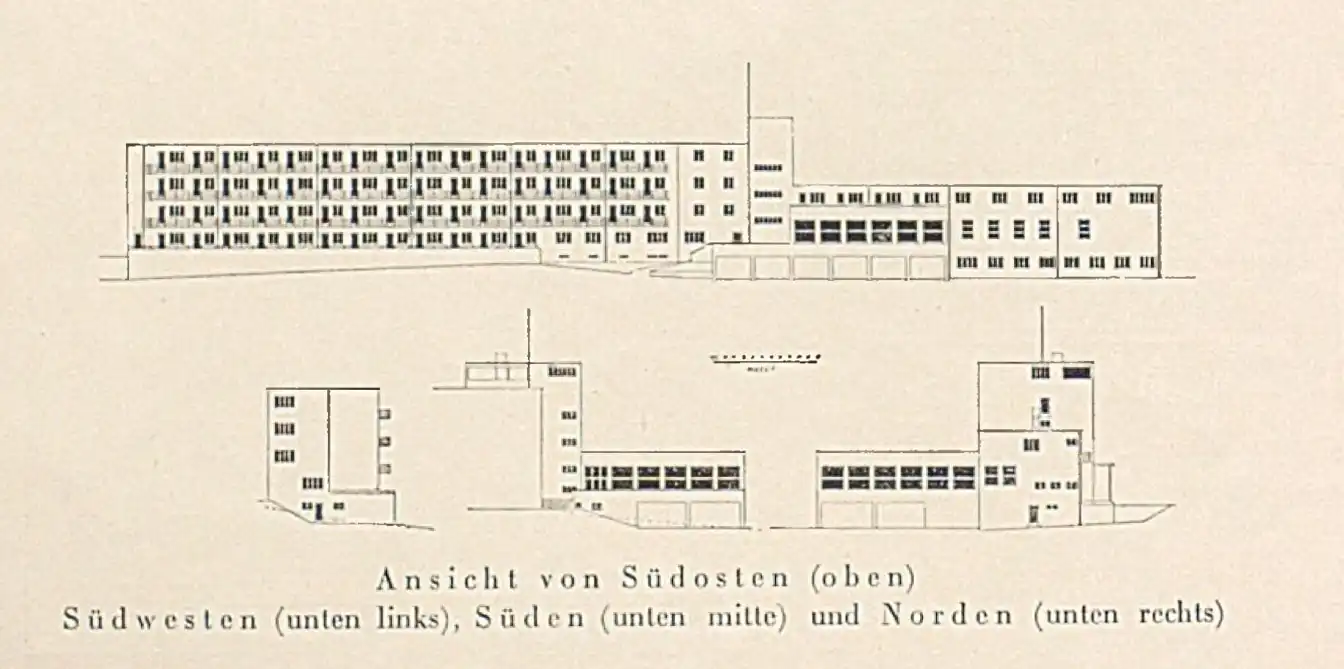

Haus auf der Alb, 1929-1930. Architect: Adolf Gustav Schneck

Haus auf der Alb, 1929-1930. Architect: Adolf Gustav Schneck

Haus auf der Alb, 1929-1930. Architect: Adolf Gustav Schneck

German Society for Merchants’ Recreation Homes

The Society, based in Wiesbaden, was founded in December 1910 on the initiative of Wiesbaden textile industrialist Joseph Baum.

The purpose of the nonprofit organization was to enable commercial and technical employees in trade and industry, as well as “less well-off” self-employed tradesmen, to take a vacation or health cure “every year or at least for several years” “for a small fee that does not significantly exceed domestic consumption.

Those seeking recreation should not be restricted in their choice of accommodation and should be able to choose from the most attractive recreational areas in Germany: from the high mountains to the North Sea and the Baltic Sea. This was intended to counteract the social and health burdens of industrialization and urbanization for those working in trade and industry, and to enable them to take a ‘time-out from a working life that was stressful for nerves, mind and body’.

The Competition

In 1929, the competition for the construction of the Urach Merchants’ Recreation Home was announced among seven renowned Württemberg architects. The building program for the vacation home for 120 people called for “no luxury building, but comfort and coziness” as well as “good sunlight and ventilation of all living and social rooms” – all under the aspect of “greatest economy and simplicity.

Adolf Gustav Schneck’s design, which ultimately won the contract, was praised for its overall layout: “The building masses are set into the terrain with great security, the good south-east orientation of all rooms and the energetically projecting wing with the common rooms and dining room are particularly noteworthy. In the angle between the residential wing and the wing with the social and dining rooms, there is a beautiful and usable terrace to the east and south’.

The Design

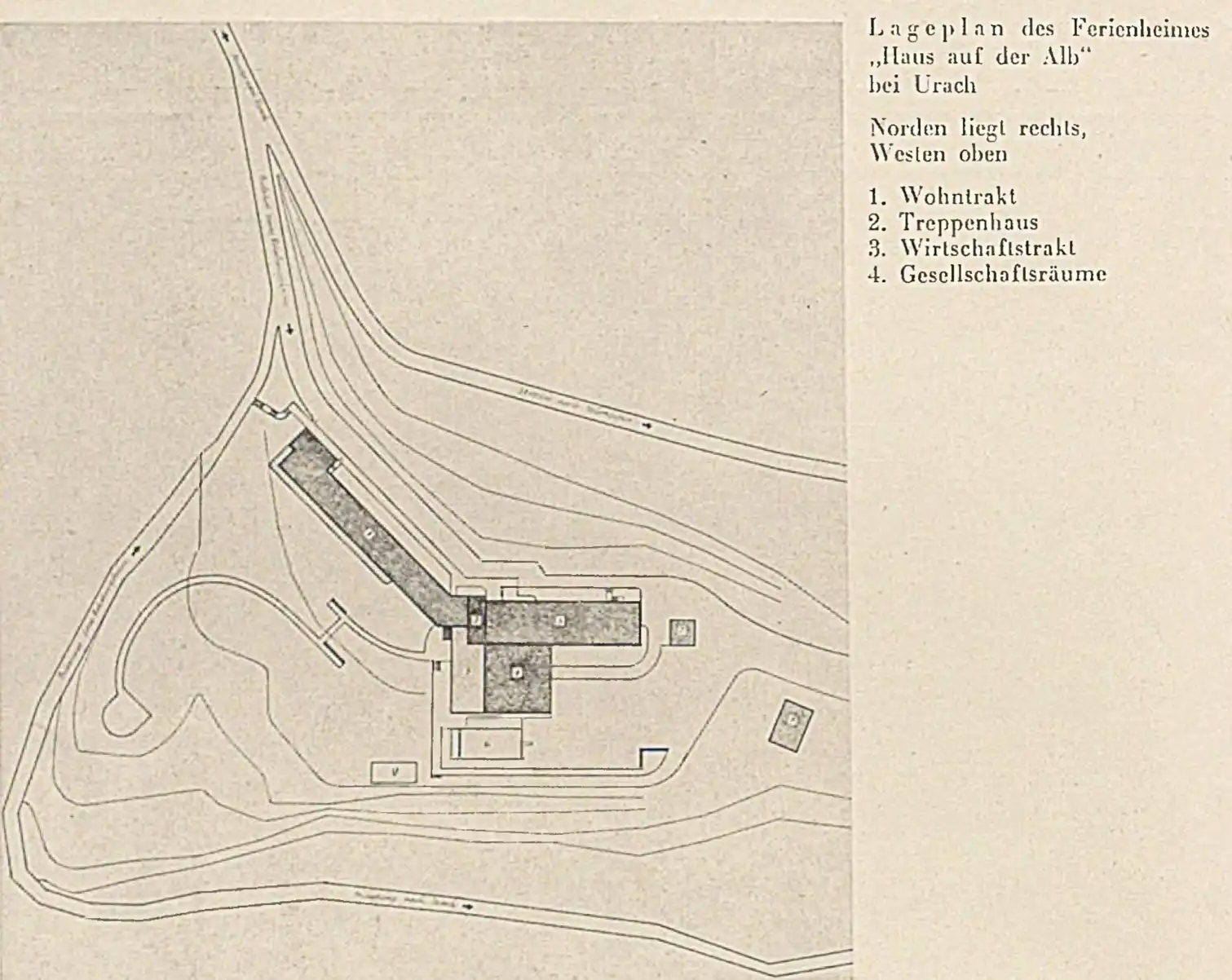

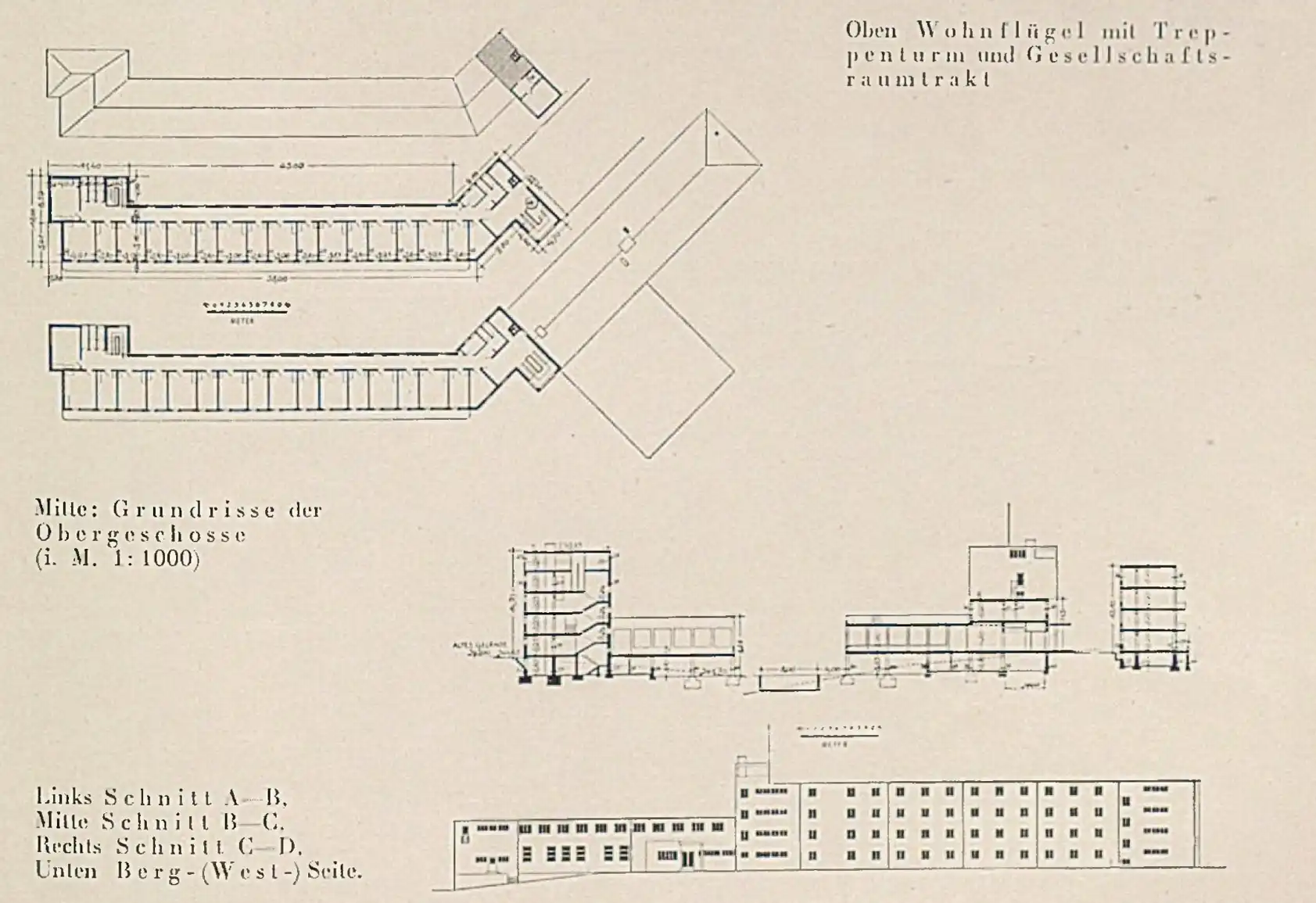

Schneck’s design is characterized by its sculptural division into four distinct, clearly separated structures. The approximately 60-meter-long, four-story guest wing with 109 beds is adjoined at an obtuse angle by a two-story wing with utility and staff rooms.

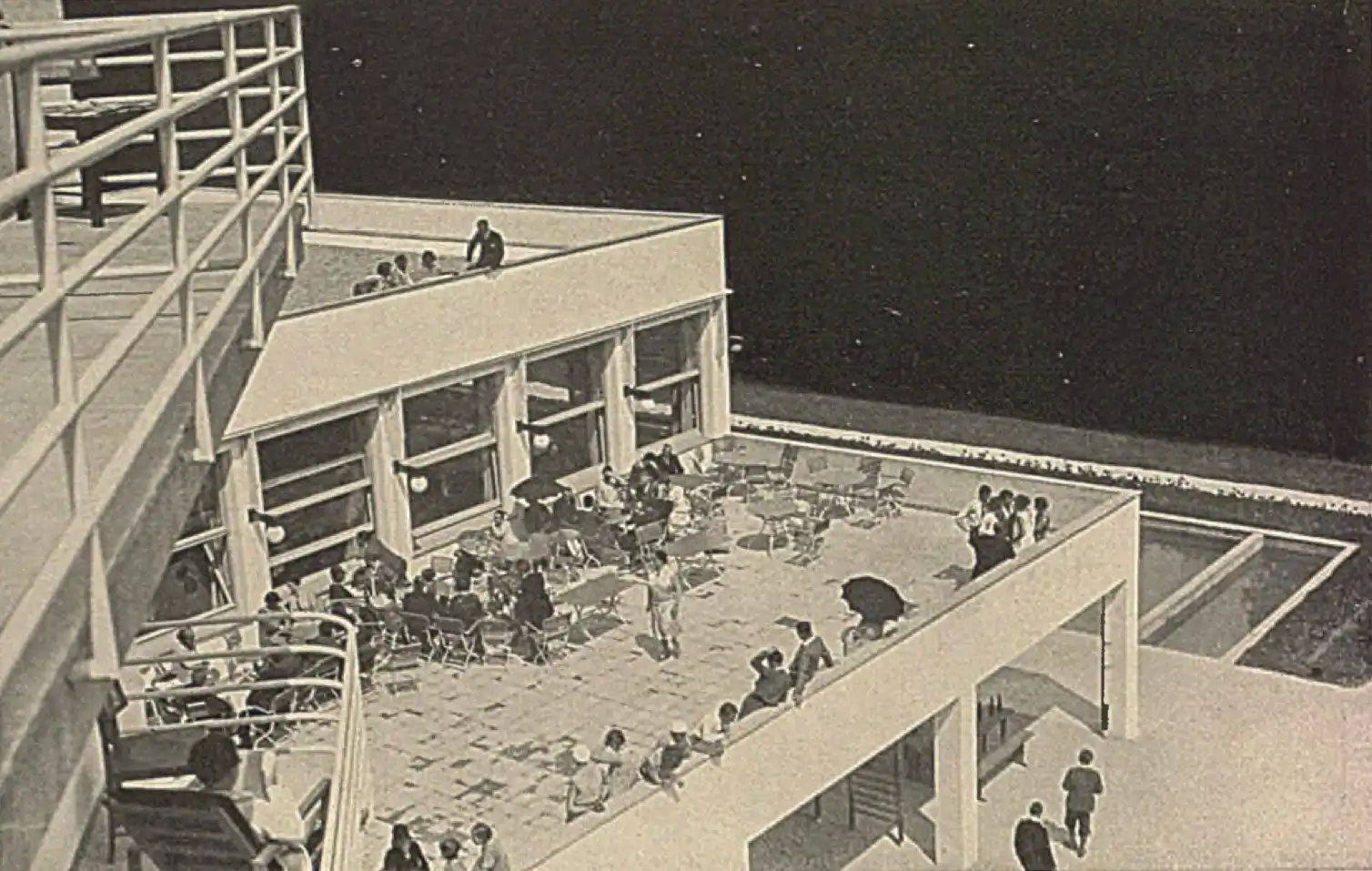

The towering staircase rises above the intersection of the two wings. On the valley side, the flat wing of the common rooms, with its large south-facing terrace, rests on pillars.

Haus auf der Alb, 1929-1930. Architect: Adolf Gustav Schneck. Contemporary photography

Haus auf der Alb, 1929-1930. Architect: Adolf Gustav Schneck. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Haus auf der Alb, 1929-1930. Architect: Adolf Gustav Schneck. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Haus auf der Alb, 1929-1930. Architect: Adolf Gustav Schneck. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Haus auf der Alb, 1929-1930. Architect: Adolf Gustav Schneck. Photo: Daniela Christmann

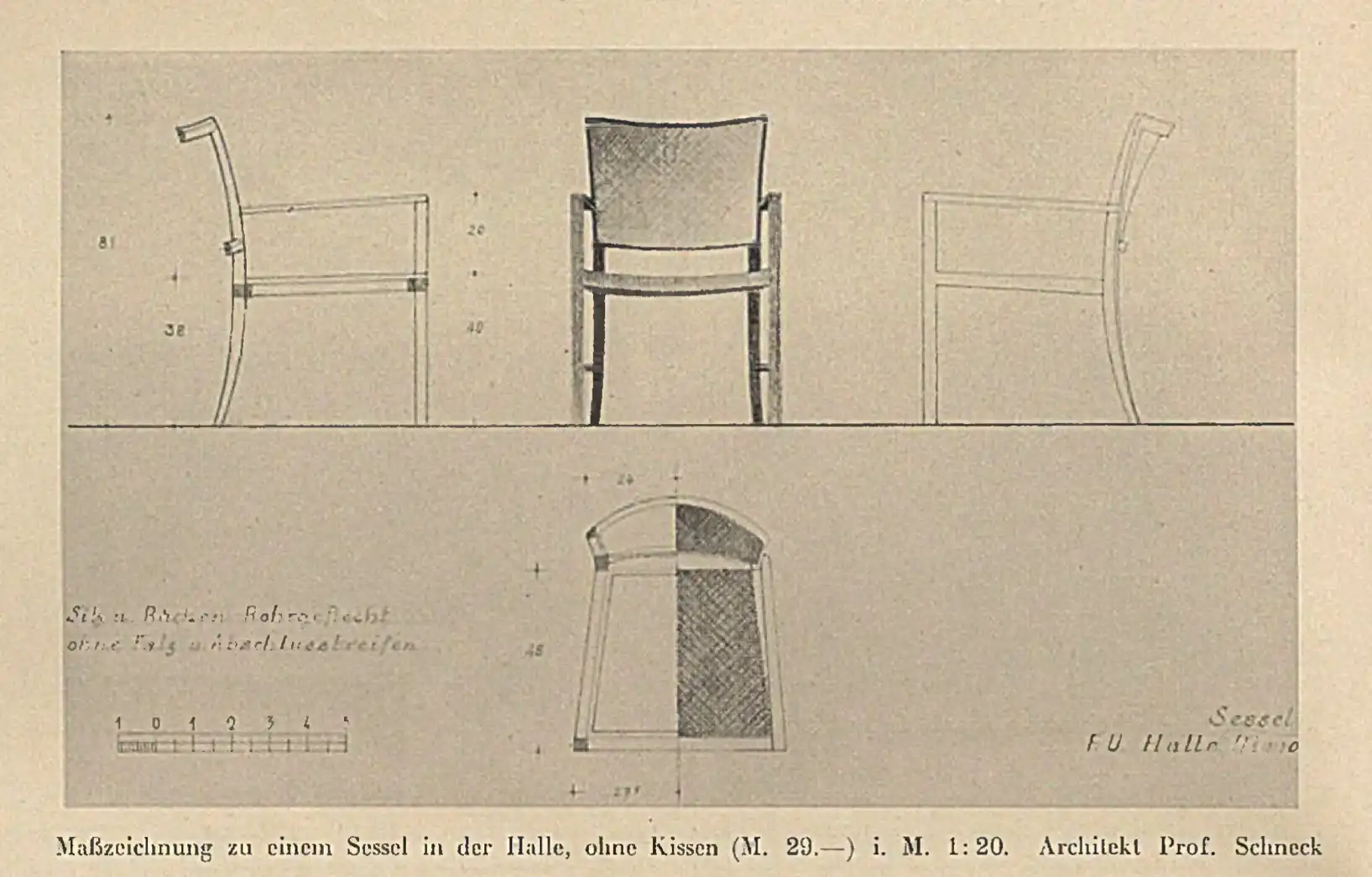

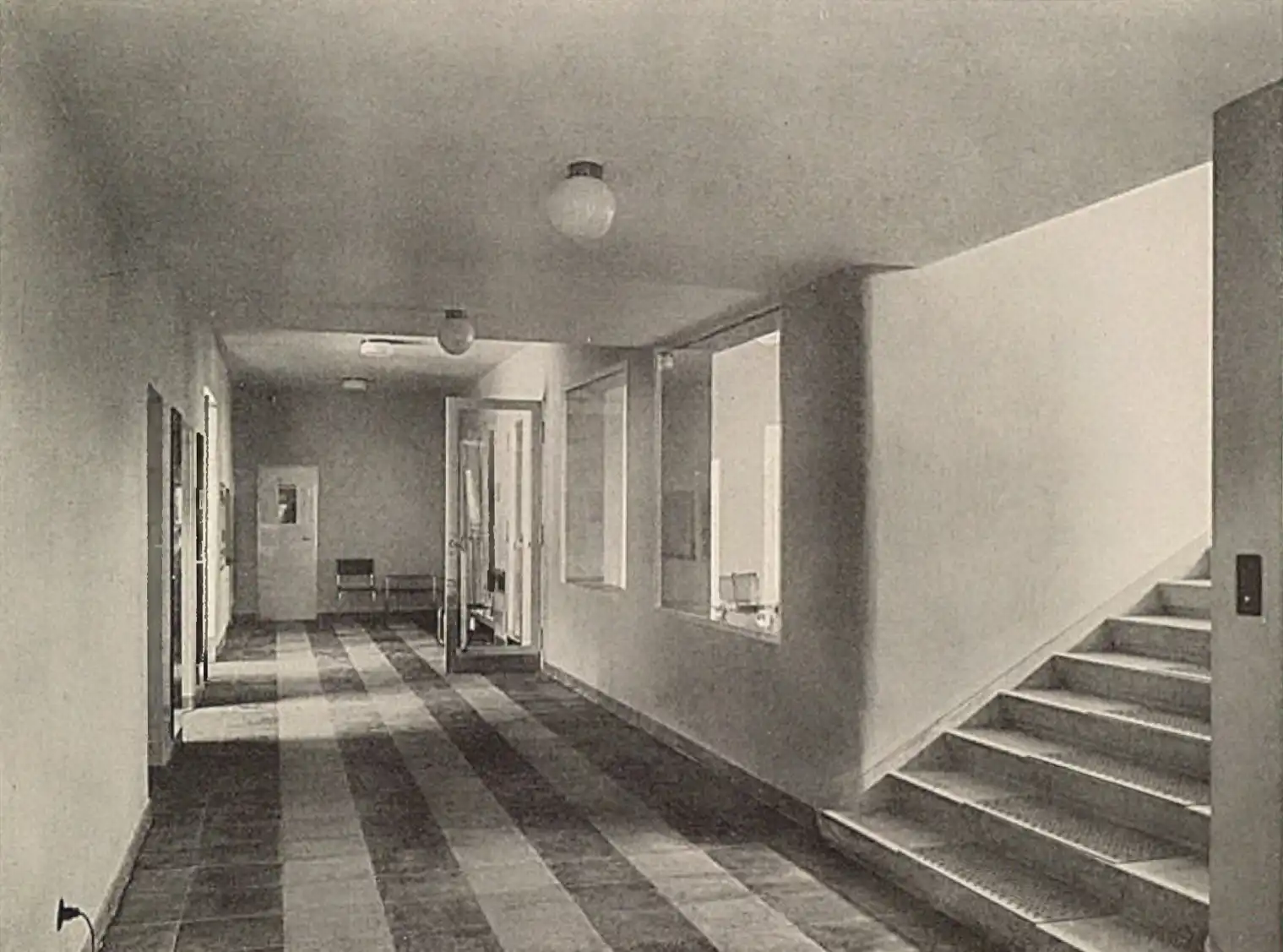

The interiors

From the beginning, Schneck had in mind the equality of all the rooms: “They all have the best orientation and position towards the sun and the wide valley. The men and women at work were to feel at home here and be able to forget their social differences.

A corridor on the northwest side of the house leads to the bedrooms.

The architect Adolf Schneck was responsible for the interior design of the house: much of the furniture was made according to his designs.

The original layout of the rooms reflects Schneck’s sense of practicality. Next to the door was the sink, mirror and wardrobe, while the lighter part of the room was reserved for the bed and a small desk by the window.

Today, the rooms meet modern standards with shower and toilet, but the functional layout has remained the same.

Haus auf der Alb, 1929-1930. Architect: Adolf Gustav Schneck. Contemporary photography

Haus auf der Alb, 1929-1930. Architect: Adolf Gustav Schneck

Haus auf der Alb, 1929-1930. Architect: Adolf Gustav Schneck. Contemporary photography

Almost every room has access to the outside, and the balconies along the southeast side of the guest wing offer a panoramic view of the Swabian Alb.

An open stair tower is the hinge of the house – it connects the 4-story guest wing with the middle section.

In the original building, the sun terrace, lounge and dining room were located side by side in three wings. It was in these central areas that communal life took place.

Haus auf der Alb, 1929-1930. Architect: Adolf Gustav Schneck. Contemporary photography

Haus auf der Alb, 1929-1930. Architect: Adolf Gustav Schneck. Contemporary photography

Georg Goldstein

As chairman of the board of the German Society for Merchants’ Recreation Homes, Dr. Georg Goldstein had assumed the role of builder and played a key role in determining the concept of the house on the Alb. In June 1933, the board of directors decided to dismiss Goldstein because he was Jewish.

Georg Goldstein had led the society since 1912 and “organized it, putting aside all personal needs, and raised it to a high level through new acquisitions and donations,” according to a DGK commemorative publication.

Forced into retirement in 1933, Goldstein became deeply involved with the increasingly persecuted Jewish community in Wiesbaden. He and his wife Margarethe were unable to follow their children into exile in England; their plans to emigrate came to nothing.

Under the supervision of the Gestapo, Goldstein was forced to participate in the confiscation of Jewish property. In March 1943, the couple was deported to Theresienstadt, where Georg Goldstein was murdered five months later. His wife, Margarete, was deported to Auschwitz in October 1944 and murdered there.

The Second World War

During the Second World War, the Urach Merchants’ Recreation Home was confiscated by the Wehrmacht and set up as a “spa and convalescent hospital” in the spring of 1940. The building was painted in camouflage and a large red cross was painted on the roof.

The Urach Reserve Hospital was not disbanded until August 1945. In the meantime, the French occupying forces had confiscated the house on the Swabian Alb and temporarily given it a new function: For two months, it housed about 170 French children as a ‘French vacation colony’.

Conversion

After a number of different uses, the listed building was renovated from 1989 to 1992 on behalf of the state of Baden-Württemberg and converted into a conference center.

The floor plan of the rooms was retained, but some of their functions were changed: the dining room became a seminar room, and a new dining room was created in the former kitchen wing.

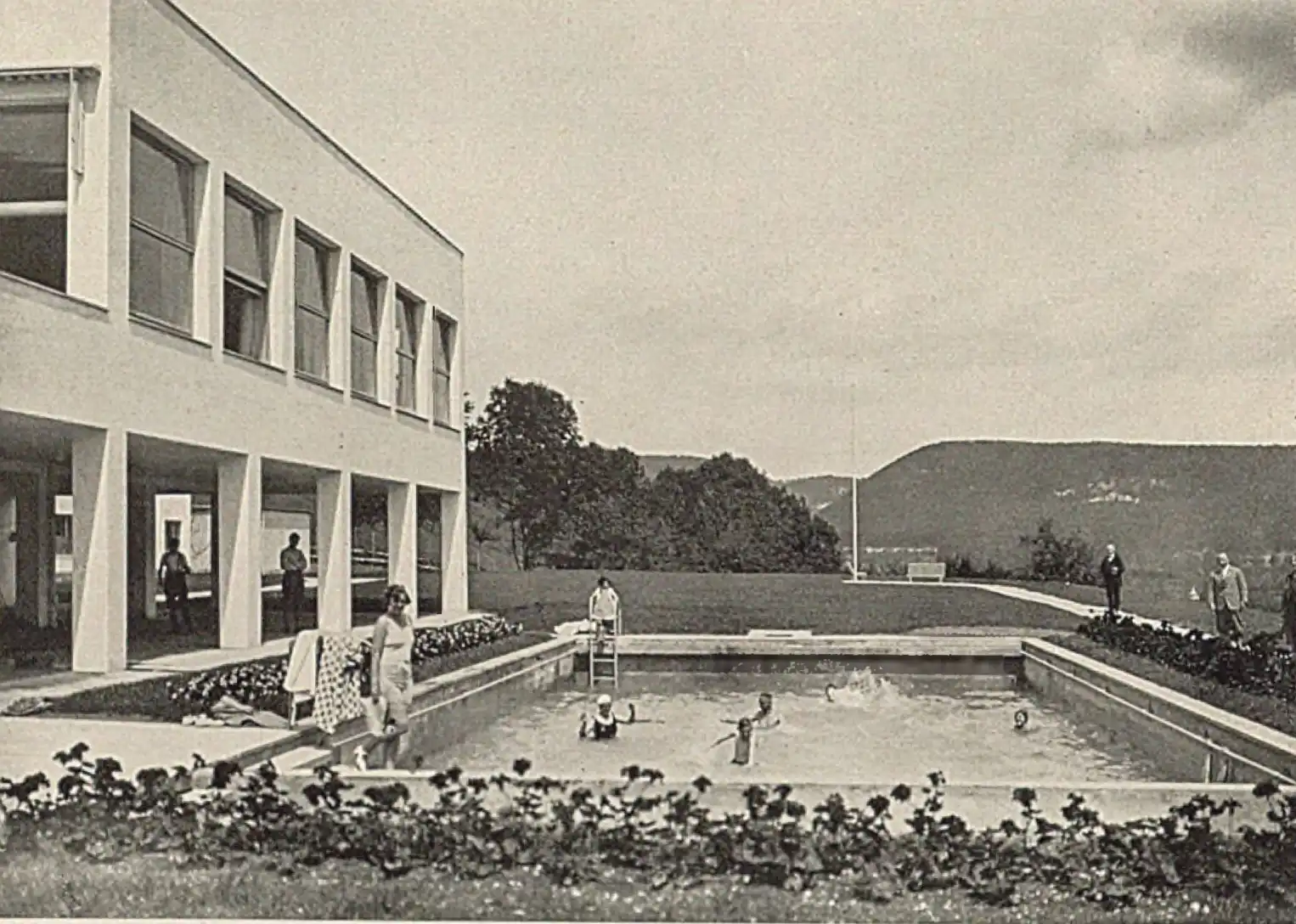

Below the meeting rooms, Schneck had created an open but covered lounge area that bordered the swimming pool. For a long time it was the first outdoor pool in Urach, a major attraction for a vacation home at that time.

Today, the sunbathing and gymnastics area has given way to a library and various rooms used by conference guests in their free time.

Today, only stone slabs in the lawn remind us of the former swimming pool. It was converted into a lawn in 1990 as part of the renovation.