1923

Design: Georg Muche

Am Horn 61, Weimar, Germany

Designed by Georg Muche for the first Bauhaus exhibition in 1923, Haus Am Horn was an experimental house of the Bauhaus in Weimar.

Haus Am Horn, 1923. Design: Georg Muche. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Haus Am Horn, 1923. Design: Georg Muche. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Haus Am Horn, 1923. Design: Georg Muche. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Haus Am Horn, 1923. Design: Georg Muche. Photo: Daniela Christmann

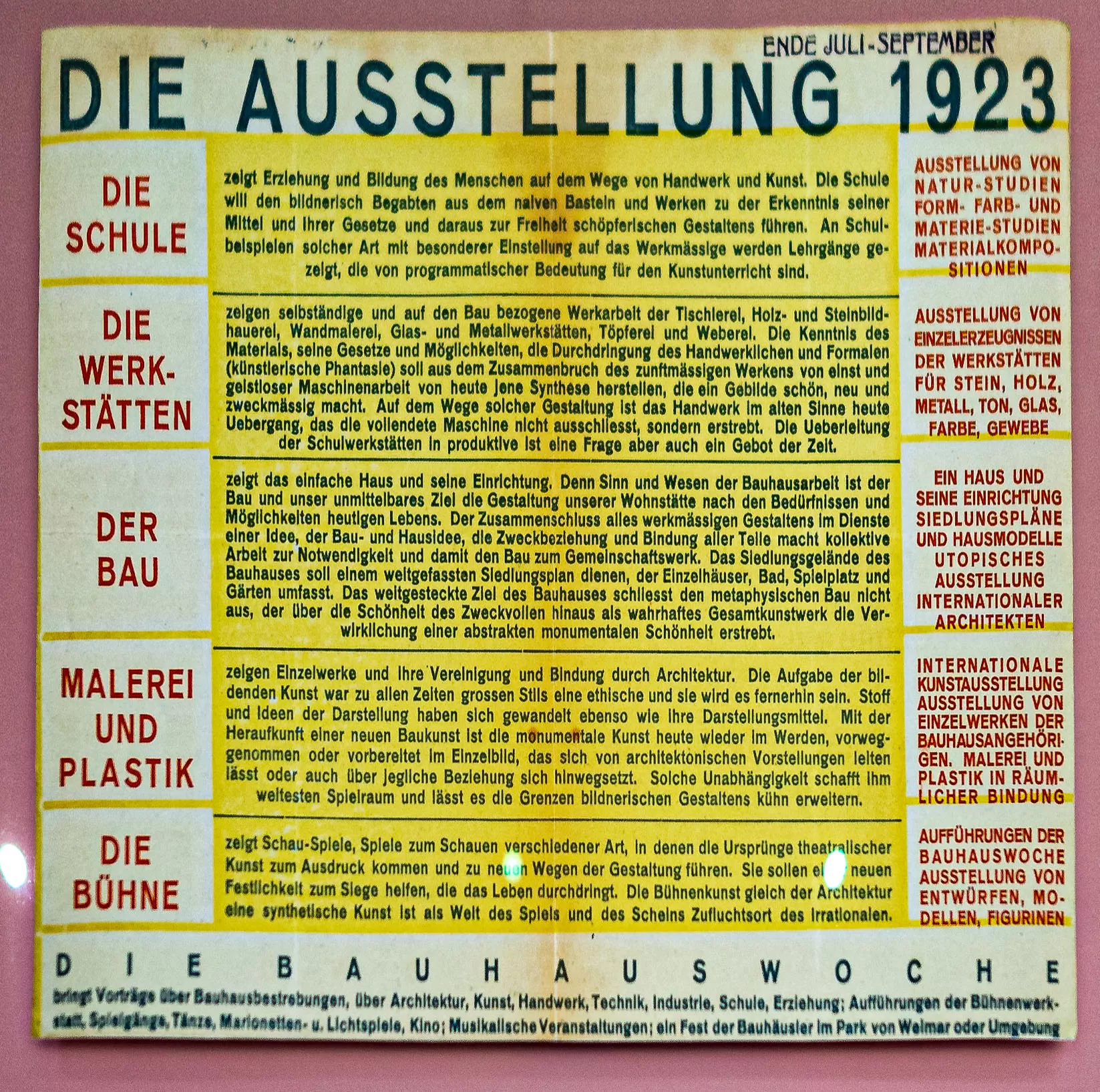

Bauhaus Exhibition 1923

The exhibition took place from August 15 to September 30, 1923. It was introduced by the Bauhaus Week, a cultural event that was very well received.

At the opening, Walter Gropius gave a lecture on: Art and Technology – A New Unity.

This was followed by other lectures, including J. J. P. Oud on the development of modern Dutch architecture.

The Haus Am Horn was presented together with an exhibition of examples of international modern architecture from the Netherlands, France, Russia, Germany and the USA.

Haus Am Horn is the only architecture realized by the Bauhaus in Weimar.

It was intended to provide a solution to the housing shortage with modular, low-cost construction and a use-oriented floor plan.

For the first time, the Bauhaus departments worked collaboratively across workshops by planning, building and equipping together.

Bauhaus Exhibition 1923

Bauhaus Housing Estate Am Horn

The first plans for the establishment of a Bauhaus housing estate on the Am Horn site emerged as early as the early 1920s.

In the summer of 1919, a group of students around Walter Determann presented the first drafts and models for the settlement.

The settlement was to be built for the members of the Bauhaus in order to provide them with living space, to promote a working and living community and to give the Bauhaus workshops a practical orientation.

In 1920, Determann submitted concrete plans for the settlement on the Am Horn site: The planned complex was strictly symmetrical. It included residential, workshop, community and sports buildings.

However, the plans for an entire settlement were not realized in Weimar, as the Bauhaus moved to Dessau in 1925.

The Bauhaus exhibition in 1923 offered the opportunity to realize at least one single experimental house.

Design Haus Am Horn

The painter and youngest Bauhaus master Georg Muche provided the design. The construction was carried out by Walter March and Adolf Meyer from the Walter Gropius building office.

The property, with a size of over 2,000 square meters, is located on the street Am Horn, which still has little traffic today. The house does not follow the orientation of its neighboring houses, but stands slightly twisted to the street to give the viewer an favorable perspective.

The floor plan is square with a side length of 12.70 m and a living area of about 120 m².

In the center of the roof sits a square structure with two-sided window bands, which is due to the room height of the living room of 4.14 meters.

To the rear of the house there is a kitchen garden divided into four parts for the residents’ self-sufficiency.

Haus Am Horn, 1923. Design: Georg Muche. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Haus Am Horn, 1923. Design: Georg Muche. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Financing

Without the financial support of the Berlin building contractor Adolf Sommerfeld, the experimental house Am Horn would hardly have been realized.

In 1920/192, Walter Gropius had already designed the Sommerfeld House in Berlin-Lichterfelde on his behalf.

Construction Materials and Insulation

Several of the contracted construction companies worked at cost price and used their materials for advertising purposes.

Jurko lightweight concrete block was used as the building material. A prefabricated lightweight block made of cement-bonded slag concrete, it promised a fast construction time with better structural-physical properties.

Torfoleum, another modern material, was used for insulation.

Slabs of industrially processed peat, set twice, brought significant savings compared to a brick wall in terms of material, transport and labor costs, as well as in the built-up area and heating requirements. Torfoleum was also laid under the screed of the floor.

Ceilings and Plaster

Ceilings were executed as hollow ceramic block ceilings with steel inlays, roofing as multi-layer bituminous sheeting.

Plastering was done with a silver-grey Terranova noble plaster, which achieved an iridescent effect through mica particles.

Windows and Window Sills

Asbestos slate panels were used for the window sills.

In the bathroom and kitchen, space-saving tilt-up windows with crystal mirror glass were installed.

Skylights in the living room were made of frosted glass, creating a soft incidence of light. Window bands, baseboards, and wall coverings in the kitchen, bathroom, and vanity were made of white, black, and red opaque mirror glass.

Floor

Rubber and triolin were used as flooring. The latter served as a substitute for linoleum, which was subject to a luxury tax.

Heating and Furnishing

In the basement there was a central heating system with a coal boiler, as well as a washing machine with gas heating and electric drive.

Gas water heaters were located in the kitchen and bathroom. Household appliances included a vacuum cleaner, bread toaster, kettle, coffee maker, hair dryer, gas stove, house telephone, and telephone.

Some furnishings, such as the gas stove, were intended purely as exhibits and were to be returned after the exhibition if no buyer could be found.

Haus Am Horn, 1923. Design: Georg Muche. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Haus Am Horn, 1923. Design: Georg Muche. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Haus Am Horn, 1923. Design: Georg Muche. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Interior Design and Color Scheme

The room layout of the house follows the principle of honeycomb construction, in which a large main room is surrounded by adjacent smaller rooms.

Half of the floor space is taken up by the central living room, which marks the middle of the floor plan. Around it are the remaining rooms: the ladies’ and men’s rooms’ rooms, the children’s room, the study, the guest room, the dining room, and the kitchen and bathroom.

This layout eliminated the need for hallways. The color concept envisaged light pastel shades, such as yellow, green or gray, which contrasted with accentuated strong colors such as the red-blue checkered floor in the dining room.

Living Room

The central living room is four meters high. It receives light through frosted glass panes of the skylights on the south and west sides.

Thus, the skylight windows consist of wrought-iron window frames that help support the weight of the ceiling. One of the windows can be tilted by a scissor mechanism.

Visual focal point in the living room is a rug by Martha Erps. The sitting area was furnished with a sofa, a table and three chairs by Marcel Breuer and the ti 1a slatted chair.

Light source was a floor lamp by Gyula Pap, whose socket is located at a height of about one meter on the wall surface.

Marcel Breuer designed the living room cabinet.

In the study alcove there was a desk and chair designed by Marcel Breuer and a crank telephone. Above the desk hung a swivel lamp designed by Carl Jakob Jucker.

Some of the furniture of the house has been preserved original and is exhibited in the Bauhaus Museum Weimar for conservation reasons. Exact replicas were made in some cases for presentation in the house.

Since some pieces of furniture no longer exist, the outlines of the pieces are marked.

Contemporary Interior Photo

Haus Am Horn, 1923. Design: Georg Muche. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Bedroom and Children’s Room

Bed, table and built-in wardrobe in the men’s bedroom were designed by Erich Dieckmann.

Used woods were black stained oak and reddish padouk. Shelves made of opaque glass were attached to the walls.

Reading and ceiling lamps were designed by László Moholy-Nagy. A reading lamp set into the wall is still preserved in its original form.

In the lady’s room, the carpet design is by Agnes Roghé, and the furniture was designed by Marcel Breuer.

Marcel Breuer’s journeyman piece was also part of the furnishings: a toilet table with two movable mirrors and a chair.

In the line of sight to the dining room and kitchen, the children’s room bordered the lady’s room.

As the only room in the house, the children’s room had a separate access to the garden.

Alma Buscher and Erich Brendel designed the furnishings, Benita Otte the carpet.

The play cabinet with mobile elements had several functions and could also be used as a puppet theater.

Red, blue and yellow wooden boards on the walls served as painting surfaces. A washstand with a hot water connection was also located in the children’s room.

Dressing table and chair, 1923. Design: Marcel Breuer. Partial reconstruction: Gerhard Oschmann. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Toy cabinet, design: Alma Buscher, Erich Brendel. Reconstruction. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Toy cabinet, design: Alma Buscher, Erich Brendel. Reconstruction. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Dining Room and Kitchen

Dining room furniture consisted of a table with a glass top, four chairs, and a built-in cabinet.

Erich Dieckmann designed all the furniture in the dining room. It is kept simple in color, in gray and black stain. In contrast, the floor is made of rubber flooring with a striking red, blue, and white checkered pattern.

Benita Otte and Ernst Gebhardt designed the kitchen as a housewife’s laboratory and one of the first built-in kitchens in Germany.

Furnishings and lighting conditions were adapted to the work processes. Cooking, frying and grilling stove was powered by gas. The wall paneling is made of white opaque glass.

Part of the furnishings are the Bogler storage jars as ceramic vessels for storing food. Designed by Theodor Bogler, they were mass-produced at the Velten-Vordamm earthenware factories.

Storage Jars, 1923. Design: Theodor Bogler. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Bauhaus Workshops’ Participation

All workshops of the Bauhaus participated in the design and execution of the model house.

Furniture workshop with Marcel Breuer (living room and ladies’ room), Alma Buscher and Erich Brendel (children’s room), Erich Dieckmann (dining room and men’s room) and Benita Otte and Ernst Gebhardt (kitchen) designed the furnishings of the individual rooms.

The metal workshop with Alma Buscher (lighting children’s room), Carl J. Jucker (desk lamps), Gyula Pap (floor lamp in the living room) and László Moholy-Nagy (lighting men’s room) designed the lamps.

Wall painting workshop with Alfred Arndt and Josef Maltan was responsible for painting the rooms.

The workshop for weaving with Lis Deinhardt (men’s room), Martha Erps (living room), Benita Otte (children’s room), Agnes Roghe (ladies’ room) and Gunta Stölzl (living room niche) designed and made the carpets.

Theodor Bogler and Otto Lindig of the Ceramic Workshop designed ceramic vessels for the house.

Groundbreaking and Completion

The foundation stone was laid on April 11, 1923, and the house was ready for occupancy on August 15, 1923.

Following the Bauhaus exhibition

At the end of the Bauhaus exhibition, the house stood empty. It belonged to the construction financier Adolf Sommerfeld, who had planned to sell the house at a profit.

Hyperinflation made a sale unlikely. Sommerfeld tried to minimize his financial loss and had all the movable furnishings transported to himself in Berlin. He continued to offer the house itself for sale to no avail.

In September 1924, after a laborious search, the house found a buyer. In the rear part of the house, a veranda and two new living rooms were added.

Postwar Years and Current Use

The house has been owned by the city of Weimar since 1951 at the latest and was occupied by various tenants until 1998. It has been a listed building since 1973.

In 1996, the building was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site as part of The Bauhaus and its sites in Weimar, Dessau and Bernau.

The Friends of the Bauhaus University Weimar leased the property from 1998 to 2017.

In 1998/99, a general renovation of the building took place during which the annexes were removed.

The city of Weimar transferred the house Am Horn to the Klassik Stiftung Weimar in 2019. Today, the house is open to the public.