1927 – 1929

Architect: Hans Herkommer

Zeppelinallee 99-103, Frankfurt am Main-Bockenheim, Germany

The Frauenfriedenskirche is a Catholic church in the Frankfurt district of Bockenheim. It was completed between 1927 and 1929 on the Ginnheimer Höhe according to the plans of architect Hans Herkommer.

Frauenfriedenskirche, 1927-1929. Architect: Hans Herkommer. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Frauenfriedenskirche, 1927-1929. Architect: Hans Herkommer. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Frauenfriedenskirche, 1927-1929. Architect: Hans Herkommer. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Background

Hedwig Dransfeld, women’s rights activist, politician and president of the German Catholic Women’s Association (KDFB), had the idea of building a Women’s Peace Church in 1916, inspired by the Battle of Verdun.

In 1916, she developed the concept of building a Women’s Peace Church on a site in the city of Marburg.

In the same year, she presented this plan to the German Bishops’ Conference, which supported the idea and suggested a site in the so-called Diaspora.

Protestant Frankfurt had experienced a strong population growth due to the migratory movements of industrialization, which brought many workers from Catholic provinces for whom there were not enough churches.

Between 1924 and 1934, seven new Catholic churches were built in working-class neighborhoods. The KDFB, together with other Catholic women’s organizations and the parish of St. Elisabeth in Frankfurt-Bockenheim, formed a working committee and began a nationwide fundraising campaign in 1918.

Despite the hardships of the post-war period, a total of 900,000 RM was collected; the idea of a Women’s Church for Peace was well received everywhere. The inflation of 1923 wiped out all the donations, and it was not until a year later that the collection was resumed, but it was only half as much as before.

The Competition

A total of 157 architects participated in the competition for the Frauenfriedenskirche. The first prize went to the “Sacrificial Way” design by the two most important representatives of Catholic church architecture in Germany, Dominikus Böhm and Rudolf Schwarz.

The competition entry was their only joint project. However, the working committee for church construction, chaired by Ernst May, decided in favor of Hans Herkommer’s design. The jury, which included Paul Bonatz, awarded him third prize.

The cornerstone was laid in 1927, and the church was consecrated by Bishop Damian von Fulda on May 5, 1929, to great national acclaim. Frauenfrieden became an independent parish in 1930.

Layout

The Frauenfriedenskirche by Hans Herkommer is a reinforced concrete building with natural and artificial stone cladding. The ground plan is rectangular. The choir is set back by the width of the side aisles and the portal front is related to the choir.

To the left of the portal is the circular baptistery. The choir, whose altar is placed directly in front of the front wall, is divided into three naves like the nave.

To the right of the church, in the style of medieval monasteries, are the courtyard for the fallen of the two world wars, surrounded on three sides by porticoes, and the parish rooms.

The ground was broken in 1926 and the first stone was laid in 1927. The courtyard, where the names of the war dead from all over Germany are inscribed on the columns, was consecrated in 1931.

Frauenfriedenskirche, 1927-1929. Architect: Hans Herkommer. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Architect Hans Herkommer

Herkommer studied architecture at the Technical University of Stuttgart from 1906 to 1910. His teachers were Theodor Fischer, Paul Bonatz, and Martin Elsaesser. In 1919 he opened his own office.

At the time of the construction of the Frauenfriedenskirche, he was already a renowned architect who tested the techniques and materials of New Architecture for their applicability to church construction. Herkommer was primarily concerned with the constructive development of traditional forms.

He was one of the first to make consistent use of the load-bearing capacity of reinforced concrete in church construction, increasingly abandoning the aesthetics of truss construction (ceiling-roof construction over cross-beams). The Frauenfriedenskirche in Frankfurt represents Herkommer’s final stage of development towards pure longitudinal truss construction.

Frauenfriedenskirche, 1927-1929. Architect: Hans Herkommer. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Frauenfriedenskirche, 1927-1929. Architect: Hans Herkommer. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Detailed planning

Herkommer planned the Frauenfriedenskirche down to the last detail. The travertine-covered reinforced concrete skeleton consists of three cubes and forms an architectural unit with the rectory, the parish rooms, and the cloister-like memorial courtyard for the fallen and missing. The wide front tower rises above the building as a western crossbeam, while the nave is closed by a transversal choir.

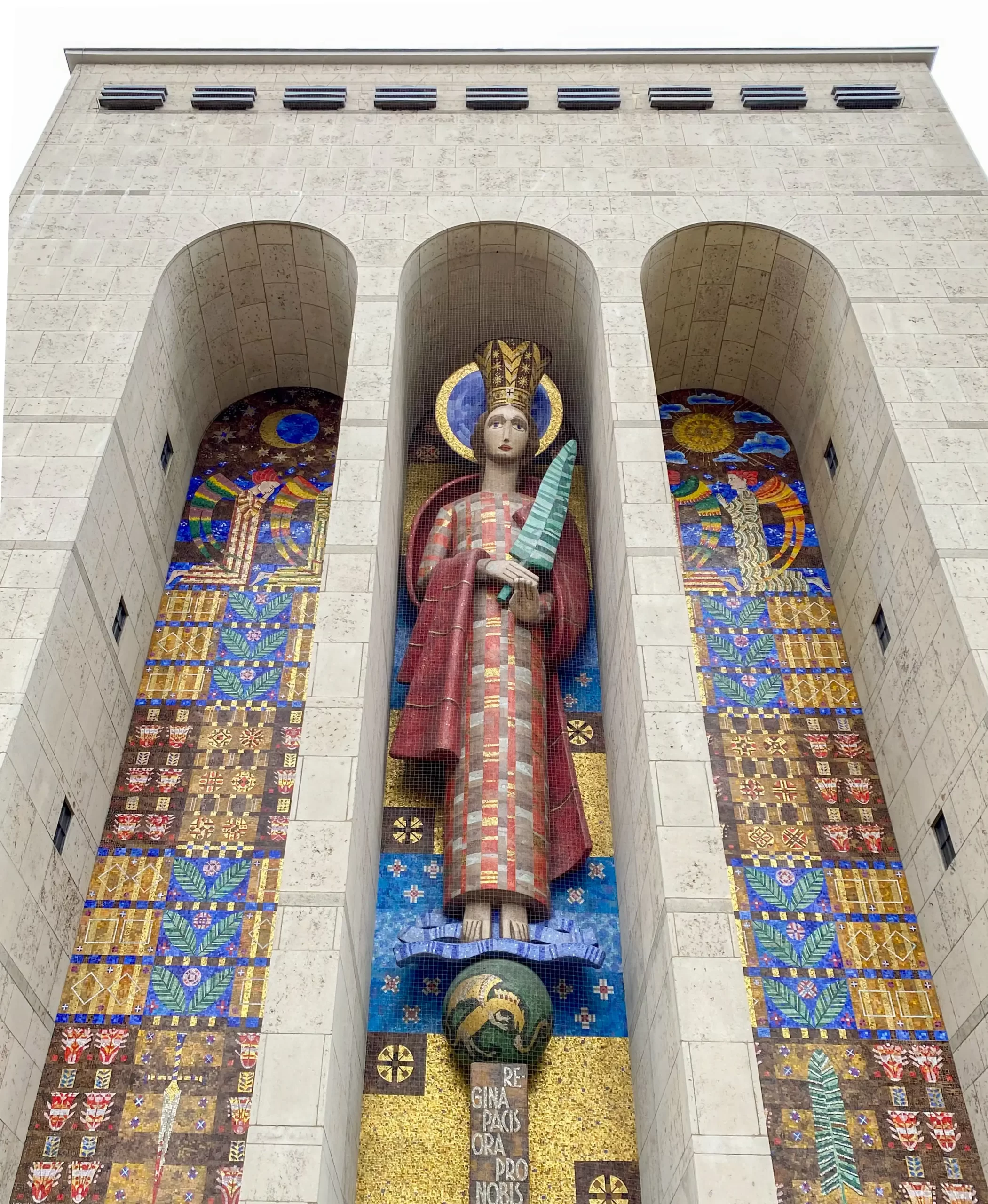

The twelve meter high mosaic statue of the Queen of Peace by the sculptor Emil Sutor rises above the portal of the Frauenfriedenskirche. The mosaic of the left arch shows the motifs of night, mourning and sword, symbolizing war; the right mosaic symbolizes peace with the depiction of sun, joy and flowers. The mosaics are the work of the painter Friedrich Stichs, executed by the company Puhl & Wagner from Berlin-Neukölln.

Frauenfriedenskirche, 1927-1929. Architect: Hans Herkommer. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Frauenfriedenskirche, 1927-1929. Architect: Hans Herkommer. Photo: Daniela Christmann

The interior

The interior is divided by high arches open to the aisles and a flat ceiling. The stained glass windows, which were destroyed during the war, used to be brighter towards the altar, providing a light guide for worshippers. They were redesigned by Joachim Pick in 1961 and now show the torn curtain of Golgotha.

Frauenfriedenskirche, 1927-1929. Architect: Hans Herkommer. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Frauenfriedenskirche, 1927-1929. Architect: Hans Herkommer. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Frauenfriedenskirche, 1927-1929. Architect: Hans Herkommer. Photo: Daniela Christmann

The Crypt

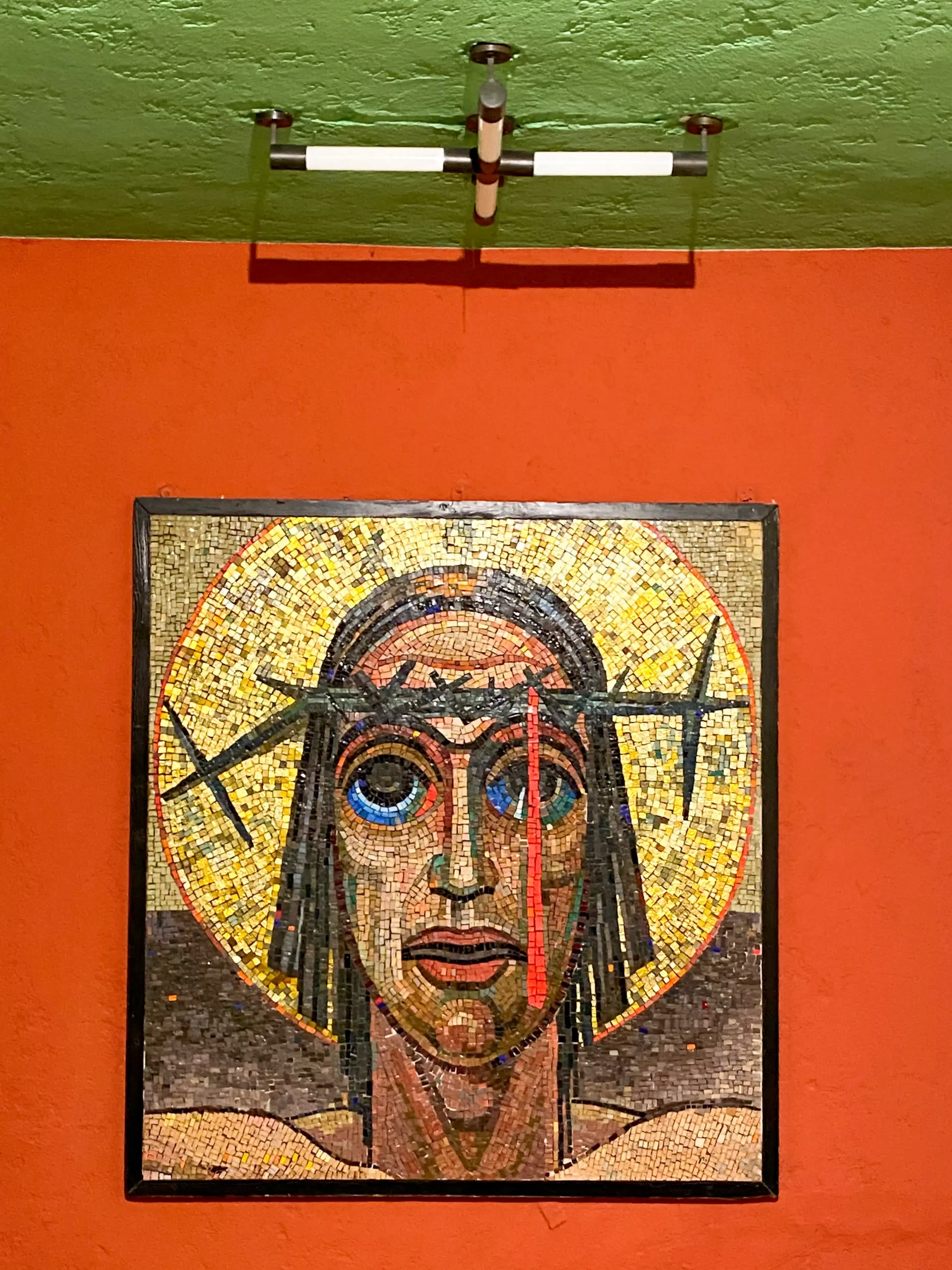

Beneath the three-nave, 18-meter-high church is a crypt containing a Pietà by Ruth Schaumann.

For the restoration of the crypt, it was agreed, based on numerous three-dimensional color studies, to preserve or reconstruct the color scheme from the time of construction.

The result was tricolored ceiling rings with blue-red-green contrasts, wall surfaces with a plaster tone and overlying two-tone glazes in green and white, and an intensely colored niche for the Caput Mortuum Pieta.

Frauenfriedenskirche, 1927-1929. Architect: Hans Herkommer. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Frauenfriedenskirche, 1927-1929. Architect: Hans Herkommer. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Frauenfriedenskirche, 1927-1929. Architect: Hans Herkommer. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Frauenfriedenskirche, 1927-1929. Architect: Hans Herkommer. Photo: Daniela Christmann

War Destruction and Reconstruction

In 1944, a bomb destroyed the roof and windows of the Frauenfriedenskirche. The building was exposed to the elements for over a year, during which time it lost its original color. In 1946, the roof was provisionally repaired, but it was not completely replaced until the 1950s.

In the 1970s, a superficial renovation was carried out with the installation of a new heating system and new heating ducts. The walls were painted a uniform light color and almost all traces of the old paint were removed.

The Restoration

When severe damage to the façade and baptistery occurred in 2015 due to ground movement, initial considerations were made to restore the building to its original condition through a new, thorough restoration.

From 2018 to 2020, the building was extensively repainted as part of a comprehensive restoration based on findings from the time of construction. The original choir is now bright orange on the sides, while the monumental altar fresco has a gray background. The various architectural details have been accentuated and highlighted. The altar, which was moved into the church in the 1970s, was also redesigned in 2020.

In 2020, the altar island and the arrangement of the pews were liturgically realigned. The new rulers are by Tobias Kammerer. The oval altar, consecrated on November 22, 2020, is in the shape of an egg, a reference to the Christian symbolism of life and resurrection.

Frauenfriedenskirche, 1927-1929. Architect: Hans Herkommer. Photo: Daniela Christmann