Böttcherstrasse, 1922-1931. Design: Bernhard Hoetger, Alfred Runge, Eduard Scotland. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Böttcherstrasse, 1922-1931. Design: Bernhard Hoetger, Alfred Runge, Eduard Scotland. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Böttcherstrasse, 1922-1931. Design: Bernhard Hoetger, Alfred Runge, Eduard Scotland. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Böttcherstrasse, 1922-1931. Design: Bernhard Hoetger, Alfred Runge, Eduard Scotland. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Böttcherstrasse, 1922-1931. Design: Bernhard Hoetger, Alfred Runge, Eduard Scotland. Photo: Daniela Christmann

1921 – 1931

Design: Bernhard Hoetger, Alfred Runge, Eduard Scotland

Böttcherstrasse, Bremen, Germany

Böttcherstrasse in the old town center of Bremen, about 110 meters long, was originally the home and workplace of barrel makers.

Background

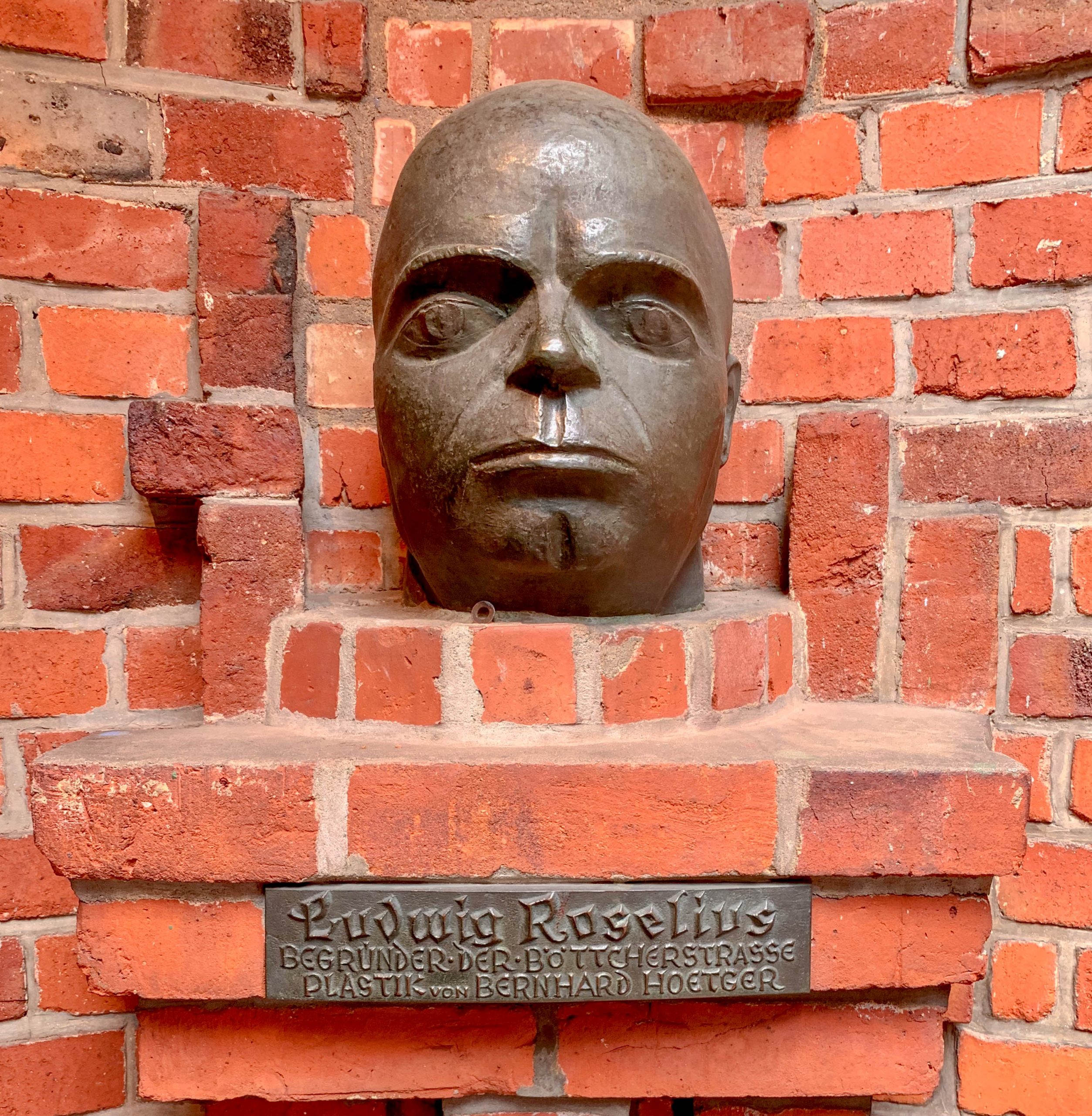

The Bremen entrepreneur Ludwig Roselius, who had made a fortune with the invention of decaffeinated coffee HAG, collected antiques and art, being particularly interested in objects of Nordic origin.

In 1902, he bought a former Kontorhaus in Bremen’s Böttcherstrasse, which was in danger of falling into disrepair.

This was the start of his involvement in Böttcherstrasse, which he subsequently had transformed into a representative showcase for his company and a total work of art.

In 1924, he acquired the heritable building right for the properties at Böttcherstrasse 15-19 from the state of Bremen for a period of 60 years.

Böttcherstrasse

After two years of negotiations, this acquisition made it possible to continue the redevelopment of Böttcherstraße on the west side.

Roselius had convinced the Senate and the city’s building authorities with his plan to create a small colony for artists and small artisans with studios, stores and apartments in the vicinity of Bremen’s market square.

After Roselius finally bought the entire street, he commissioned the architects Alfred Runge and Eduard Scotland as well as the artist Bernhard Hoetger to build or demolish and rebuild a total of six houses.

Between 1923 and 1926, a whole series of houses were built in the brick expressionist style, mostly according to the plans of the architects Runge and Scotland.

The result was an expressionist ensemble with extensive facade decoration and figural ornamentation.

Robinson Crusoe Haus

The Robinson Crusoe House (Böttcherstrasse 1) was built in 1931 as the last house on the street.

It was designed by Karl von Weihe and Ludwig Roselius.

Roselius chose the novel character Robinson Crusoe as the godfather for the house, as he exemplifies the Hanseatic drive and pioneering spirit.

The interior was designed by the architects Alfred Runge and Eduard Scotland.

The furnishings of the house have been almost completely lost in the meantime.

In the staircase, wooden panels with scenes from the story of Robinson Crusoe, carved and colored by Theodor Schultz-Walbaum, have survived.

On the first floor are the twelve colored leaded glass windows made by Bernhard Hoetger in 1926 as well as the sculptures ‘Silver Lion, Carrying the Day’ and ‘Panther, Carrying the Night’ made of bronze in 1913.

Bernhard Hoetger, Silver lion, carrying the day, bronze, 1913. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Haus St. Petrus

Haus St. Petrus (Böttcherstrasse 3-5) was built between 1923 and 1927 according to plans by architects Alfred Runge and Eduard Scotland. It served as a restaurant until its destruction during war.

Roselius Haus

The Roselius House (Böttcherstrasse 6) is the oldest of the buildings in the street with foundation walls dating back to 14th century.

It first served Ludwig Roselius as his administrative headquarters and was expanded in 1928 to plans by Carl Eeg and Alfred Runge to house Roselius extensive collection of art.

Haus der Sieben Faulen

Haus der Sieben Faulen (Böttcherstrasse 7) was built between 1924 and 1927 to plans by Alfred Runge and Eduard Scotland. It housed the advertising rooms of Kaffee-HAG and the offices of Deutscher Werkbund.

The figures of the Sieben Faulen on the gable facing the street Hinter dem Schütting, which give the building its name, were created between 1924 and 1926 to designs by sculptor Aloys Röhr.

Today, only the former tasting room of the Kaffee-HAG with tiled walls has been preserved.

Haus des Glockenspiels

Haus Glockenspiel (Böttcherstrasse 4) was built between 1922 and 1924 by converting two old warehouses to plans by Alfred Runge and Eduard Scotland.

A first carillon was installed in 1934 and consisted of thirty bells made of Meissen porcelain.

Ten carved and colorfully painted wooden panels with motifs of the ocean conquerors, the explorers and adventurers who crossed the ocean by ship or by air, based on designs by Bernhard Hoetger, move sideways in a tower to the chimes.

After destruction during war, a second carillon was erected in 1954, and was replaced by a third carillon during renovation work in 1991. Hoetger’s wooden panels survived the war undamaged.

Böttcherstrasse, 1922-1931. Design: Bernhard Hoetger, Alfred Runge, Eduard Scotland. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Böttcherstrasse, 1922-1931. Design: Bernhard Hoetger, Alfred Runge, Eduard Scotland. Photo: Daniela Christmann

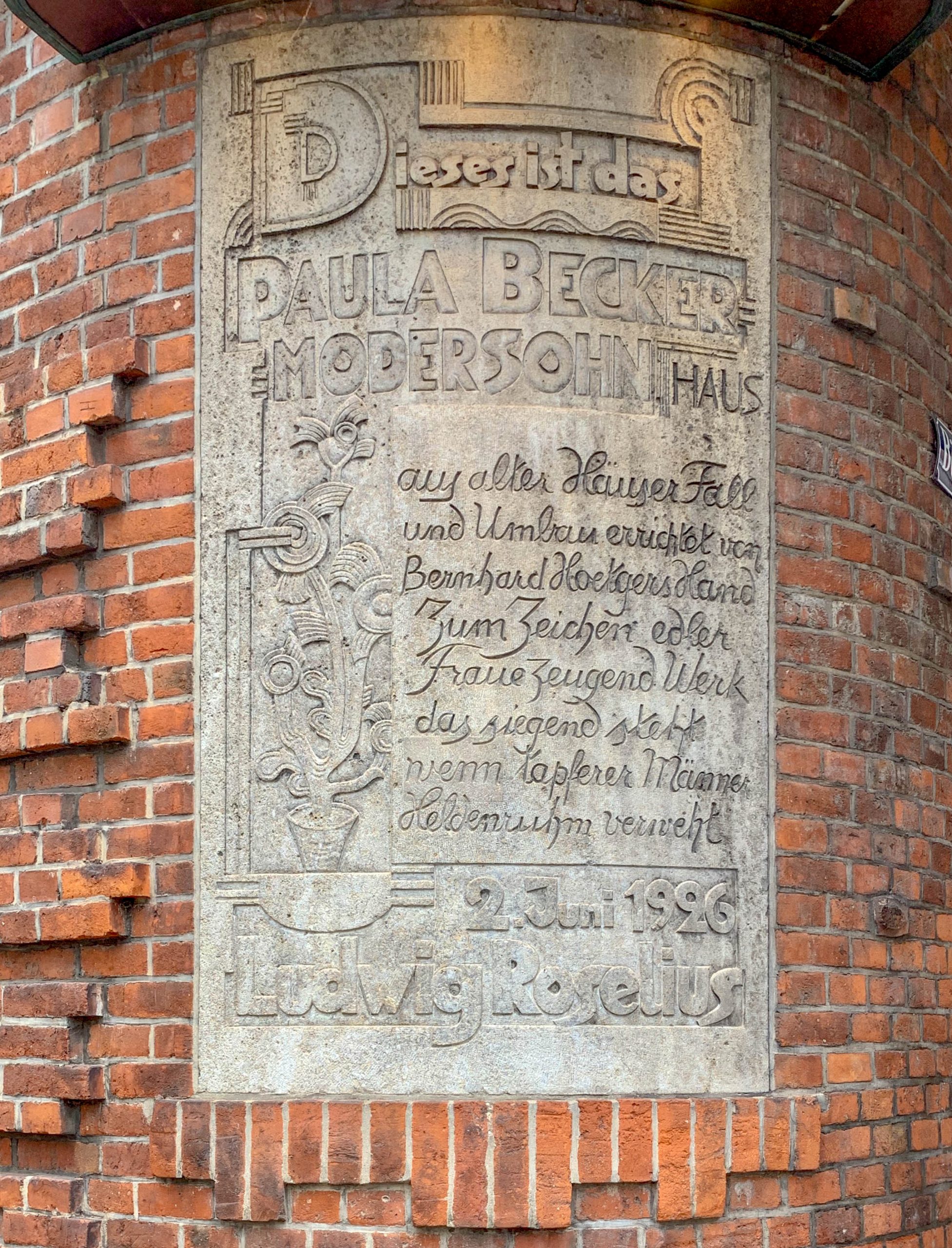

Paula Modersohn-Becker Haus

Paula Modersohn-Becker House (Böttcherstrasse 8-9) was built between 1926 and 1927 to designs by Bernhard Hoetger.

It housed a store for local arts and crafts, a restaurant, an exhibition room, and workshops for artisans in the courtyard.

A room on the third floor was reserved for the works of artist Paula Modersohn-Becker.

It was the first museum ever dedicated to a female artist.

The Paula Modersohn Becker House was originally connected to the gable of the House of the Sieben Faulen by a bridge.

Relief Hoetger

The window above the entry to Böttcherstrasse, designed by Bernhard Hoetger as a pictorial work, was replaced in 1936 at the insistence of the Nazis by Hoetger’s relief in gilded bronze of the Archangel Michael.

The fountain in the courtyard of Haus der Sieben Faulen with Bremer Stadtmusikanten on the fountain pipe and clay reliefs of the Sieben Faulen is also a design by Bernhard Hoetger.

During reconstruction of the building, that was severely damaged during war, the towers and the Shield wall were considerably simplified. The craftsmen’s courtyard was opened up to the street.

Böttcherstrasse, 1922-1931. Design: Bernhard Hoetger, Alfred Runge, Eduard Scotland. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Böttcherstrasse, 1922-1931. Design: Bernhard Hoetger, Alfred Runge, Eduard Scotland. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Böttcherstrasse, 1922-1931. Design: Bernhard Hoetger, Alfred Runge, Eduard Scotland. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Haus Atlantis

In 1931, the Atlantis House (Böttcherstrasse 2) was completed. It differs from older buildings on Böttcherstrasse in its materials of glass, steel and concrete.

Built from 1929 to 1931 to designs by Bernhard Hoetger based on the ideas of Ludwig Roselius and Herman Wirth, the demonstratively modern and functional building errected with reinforced concrete was intended for an institute for the study of legendary Atlantis.

In 1933, the Museum Väterkunde, which Roselius had commissioned Hans Müller-Brauel to build in 1927, moved into the Atlantis House.

The controversial project, in which Ludwig Roselius housed his extensive prehistoric collections, wanted to derive Nordic as well as American culture from the lost Atlantis.

Facade

The facade, reframed in the postwar period, was originally gridded and vertically articulated by steel columns extending to the apex of the roof.

This structural framework supported a wood-carved façade program designed by Hoetger above the entrance axis.

The so-called Tree of Life was a monumental pictorial work including a wheel of the year, a cross and a sun disk. It was a cultural symbolic representation for the beginning of life, from which the beginning of the year and thus at the same time the human being grows.

The wooden Tree of Life was fiercely opposed by the Nazis and ultimately burned during the war.

The facade, renovated in 1954 by architects Max Säume and Günther Hafemann with a depiction of the planets, was hidden behind an ornamented brick wall created between 1964 and 1965 by artist Ewald Mataré.

Böttcherstrasse, 1922-1931. Design: Bernhard Hoetger, Alfred Runge, Eduard Scotland. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Böttcherstrasse, 1922-1931. Design: Bernhard Hoetger, Alfred Runge, Eduard Scotland. Photo: Daniela Christmann

Since 1935, the attacks of the Nazis against Böttcherstraße increased. The press, which was in line with the Nazis, demanded a reconstruction and even the demolition of some parts of Böttcherstrasse.

In 1937, Albert Speer placed Böttcherstrasse under a preservation order as an example of the so-called decayed art of the Weimar period.

In 1944, large parts of Böttcherstraße were destroyed.

Renovation

The facades of Böttcherstrasse were largely restored to their original condition until 1954, financed by the Kaffee-HAG company.

In 1973, the street was again put under heritage protection. In 1999, the street was extensively renovated.